Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment and Management of Problems Related to Male Reproductive Processes

Conditions Affecting the Testes and Adjacent Structures

Conditions Affecting the Testes and

Adjacent Structures

UNDESCENDED TESTIS (CRYPTORCHIDISM)

Cryptorchidism is a congenital condition characterized by fail-ure of one or both of

the testes to descend into the scrotum. One or both testes may be absent. The

testis may be located in the ab-dominal cavity or inguinal canal. If the testis

does not descend as the boy matures, a surgical procedure known as orchiopexy

is per-formed to position it properly. An incision is made over the inguinal

canal, and the testis is brought down and anchored in the scrotum.

ORCHITIS

Orchitis is an inflammation of the testes (testicular congestion)caused by

pyogenic, viral, spirochetal, parasitic, traumatic, chem-ical, or unknown

factors. Mumps is one such factor. Mumps vac-cination is recommended for

postpubertal men who have not been infected. When postpubertal men contract

mumps, about one in five develops some form of orchitis 4 to 7 days after the

jaw and neck swell. The testis may show some atrophy. In the past, sterility

and impotence often resulted. Today, a man who has never had mumps and who is

exposed to the disease receives gamma-globulin immediately; the disease is

likely to be less se-vere, with minimal or no complications.

Medical Management

If the cause of orchitis is bacterial, viral,

or fungal, therapy is di-rected at the specific infecting organism. Rest,

elevation of the scrotum, ice packs to reduce scrotal edema, antibiotics,

analgesic agents, and anti-inflammatory medications are recommended.

EPIDIDYMITIS

Epididymitis is an infection of the epididymis that usually de-scends from an

infected prostate or urinary tract. It may also de-velop as a complication of

gonorrhea. In men younger than age 35, the major cause of epididymitis is Chlamydia trachomatis. The in-fection

passes upward through the urethra and the ejaculatory duct and then along the

vas deferens to the epididymis.

The

patient complains of unilateral pain and soreness in the inguinal canal along

the course of the vas deferens and then de-velops pain and swelling in the

scrotum and the groin. The epi-didymis becomes swollen and extremely painful;

the patient’s temperature is elevated. The urine may contain pus (pyuria) and

bacteria (bacteriuria), and the patient may experience chills and fever.

Medical Management

If the patient is seen within the first 24

hours after onset of pain, the spermatic cord may be infiltrated with a local

anesthetic agent to relieve pain. If the epididymitis is from a chlamydial

infection, the patient and his sexual partner must be treated with

antibi-otics. The patient is observed for abscess formation as well. If no improvement occurs

within 2 weeks, an underlying testicular tumor should be considered. An

epididymectomy (excision of the epididymis from the testis) may be performed

for patients with recurrent, incapacitating episodes of epididymitis or for

those with chronic, painful conditions. With long-term epididymitis, the

passage of sperm may be obstructed. If the obstruction is bi-lateral,

infertility may result.

Nursing Management

The patient is placed on bed rest, and the

scrotum is elevated with a scrotal bridge or folded towel to prevent traction

on the sper-matic cord and to promote venous drainage and relieve pain.

Anti-microbial agents are administered as prescribed until the acute

inflammation subsides. Intermittent cold compresses to the scro-tum may help

ease the pain. Later, local heat or sitz baths may help resolve the

inflammation. Analgesic medications are admin-istered for pain relief as

prescribed.

The nurse instructs the patient to avoid

straining, lifting, and sexual stimulation until the infection is under

control. He should continue taking analgesic agents and antibiotics as

prescribed and using ice packs if necessary to relieve discomfort. He needs to

know that it may take 4 weeks or longer for the epididymis to re-turn to

normal.

TESTICULAR CANCER

Testicular cancer is the most common cancer in men 15 to35

years of age. Although testicular cancer occurs most often be-tween the ages of

15 and 40, it can occur in males of any age. It is a highly treatable and

usually curable form of cancer. An es-timated 7,500 men are diagnosed with

testicular cancer each year, and approximately 400 die from testicular cancer

annually (American Cancer Society, 2002).

The testicles contain several types of cells,

each of which may develop into one or more types of cancer. The type of cancer

de-termines the appropriate treatment and affects the prognosis. Testicular

cancers are classified as germinal or nongerminal (stro-mal); secondary

testicular cancers may also occur.

Germinal Tumors

Over 90% of all cancers of the testicle are

germinal; geminal tumors may be further classified as seminomas or

nonseminomas. About half of all geminal tumors are seminomas, or tumors that

develop from the sperm-producing cells of the testes. Nonseminoma ger-minal

cell tumors tend to develop earlier in life than seminomas, usually occurring

in men in their 20s. Examples of nonseminomas include teratocarcinomas,

choriocarcinomas, yolk sac carcino-mas, and embryonal carcinomas. Seminomas

tend to remain lo-calized, whereas nonseminomatous tumors grow quickly.

Nongerminal Tumors

Testicular cancer may also develop in the

supportive and hormone-producing tissues, or stroma, of the testicles. These

tumors ac-count for about 4% of testicular tumors in adults and 20% of

testicular tumors in children. The two main types of stromal tu-mors are Leydig

cell tumors and Sertoli cell tumors. Although these tumors infrequently spread

beyond the testicle, a small number of these tumors metastasize and tend to be

resistant to chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Secondary Testicular Tumors

Secondary testicular tumors are those that

have metastasized to the testicle from other organs. Lymphoma is the most

common cause of secondary testicular cancer. Cancers may also spread to the

testicles from the prostate gland, lung, skin (melanoma), kid-ney, and other organs.

The prognosis for these cancers is usually poor because these cancers generally

also spread to other organs. Treatment depends on the specific type of cancer

(American Cancer Society, 2002).

Risk Factors

The risk for testicular cancer is several

times greater in men with any type of undescended testis than in the general

population (Bosl, Bajorin, Scheinfeld et al., 2001). Risk factors include a

family history of testicular cancer and cancer of one testicle, which increases

the risk for the other testicle. Race and ethnicity have been identified as

risk factors: Caucasian American men have a five times greater risk than that

of African American men and more than double the risk of Asian American men.

Occupational hazards, including exposure to chemicals encountered in mining,

oil and gas production, and leather processing, have been sug-gested as

possible risk factors. Prenatal exposure to DES may also be a risk factor, but

evidence is not strong (American Cancer Society, 2002). Vasectomy, once

considered a possible risk factor, has been shown in recent studies not to be a

risk factor (Cox, Sneyd, Paul et al., 2002).

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms appear gradually, with a mass or

lump on the tes-ticle and generally painless enlargement of the testis. The

patient may complain of heaviness in the scrotum, inguinal area, or lower

abdomen. Backache (from retroperitoneal node extension), ab-dominal pain,

weight loss, and general weakness may result from metastasis. Enlargement of

the testis without pain is a significant diagnostic finding. Testicular tumors

tend to metastasize early, spreading from the testis to the lymph nodes in the

retroperi-toneum and to the lungs.

Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

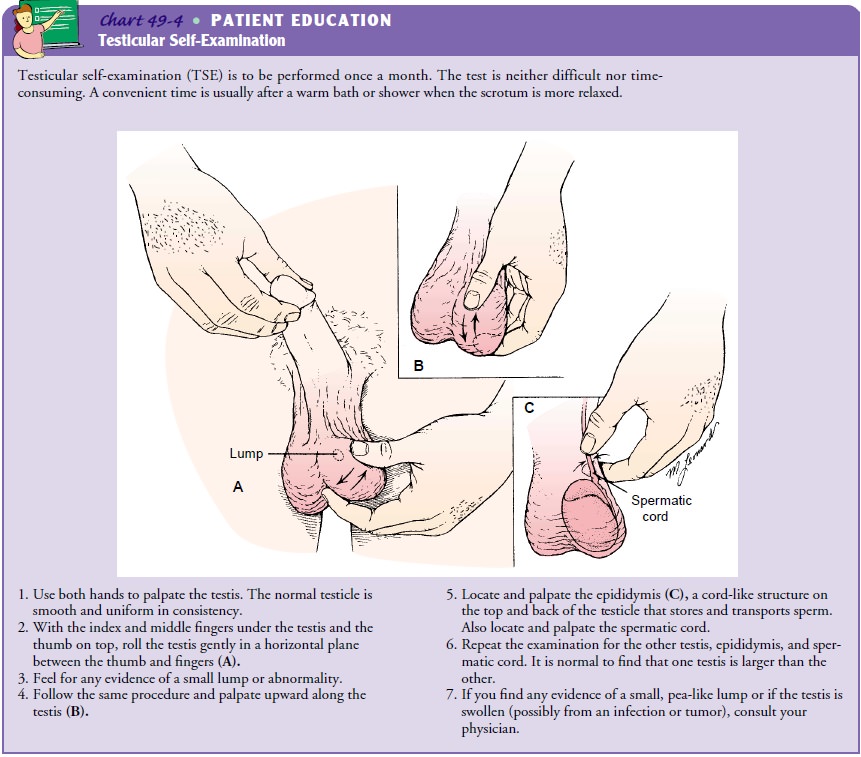

Monthly testicular self-examinations (TSEs)

are effective in de-tecting testicular cancer (Chart 49-4). Teaching men of all

ages to perform TSE is an important health promotion intervention for early

detection of testicular cancer. Since testicular cancer oc-curs most often in

young adults, testicular self-examination should begin during adolescence.

Human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein are tumor markers that may be elevated in patients with testicular cancer. (Tumor markers are substances synthesized by the tumor cells and released into the circulation in abnormal amounts.) Tumor marker levels in the blood are used for diagnosis, staging, and monitoring the response to treatment. Other diagnostic tests include intravenous urography to detect any ureteral devi-ation caused by a tumor mass; lymphangiography to assess the extent of tumor spread to the lymphatic system; ultrasound to determine the presence and size of the testicular mass; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to determine the extent of the disease in the lungs, retroperitoneum, and pelvis. Micro-scopic analysis of tissue is the only definitive way to determine if cancer is present but is usually performed at the time of surgery rather than as a part of the diagnostic workup to reduce the risk of promoting spread of the cancer (American Cancer Society, 2000).

Medical Management

Testicular cancer is one of the most curable

solid tumors. The goals of management are to eradicate the disease and achieve

a cure. Treatment selection is based on the cell type and the anatomic extent

of the disease. The testis is removed by orchi-ectomy through an inguinal

incision with a high ligation of the spermatic cord. A gel-filled prosthesis

can be implanted. After unilateral orchiectomy for testicular cancer, most patients

expe-rience no impairment of endocrine function. Other patients, however, have

decreased hormonal levels, suggesting that the un-affected testis is not

functioning at normal levels. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection to prevent

lymphatic spread of the cancer may be performed after orchiectomy. Although

libido and or-gasm are usually unimpaired after retroperitoneal lymph node

dissection, the patient may develop ejaculatory dysfunction with resultant

infertility. Thus, sperm banking before surgery may be considered (Agarwa,

2000; Zapzalka et al., 1999).

Postoperative

irradiation of the lymph nodes from the di-aphragm to the iliac region is used

in treating seminomas. Radi-ation is delivered only to the affected side; the

other testis is shielded from radiation to preserve fertility. Radiation is

also used for patients whose disease does not respond to chemotherapy or for

whom lymph node surgery is not recommended. Lymphan-giograms and CT scans are

used to determine spread of the dis-ease to the lymph nodes.

Testicular

carcinomas are highly responsive to chemotherapy. (Bosl et al., 2001)

Chemotherapy with cisplatin-based regimens results in a high percentage of

complete remissions. Good results may be obtained by combining different types

of treatment, in-cluding surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Even

with disseminated testicular cancer, the prognosis is favorable, and the

disease is probably curable because of advances in diagnosis and treatment.A

patient with a history of one testicular tumor has a greater chance of

developing subsequent tumors. Follow-up studies in-clude chest x-rays,

excretory urography, radioimmunoassay of human chorionic gonadotropins and

alpha-fetoprotein levels, and examination of lymph nodes to detect recurrent malignancy.

Long-term side effects associated with

treatments for testicu-lar cancer include kidney damage, hearing problems,

gonadal damage, neurological changes, and rarely secondary cancers

(Kollmannsberger, Kuzcyk, Mayer et al., 1999). Research on treatment regimens

with less toxicity and the use of cytoprotec-tants is ongoing.

Nursing Management

Nursing management includes assessment of the

patient’s physi-cal and psychological status and monitoring the patient for

re-sponse to and possible effects of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation

therapy. In addition, be-cause the patient may have difficulty coping with his

condition, issues related to body image and sexuality are addressed. He needs

encouragement to maintain a positive attitude during what may be a long course

of therapy. He also needs to know that radiation therapy will not necessarily

prevent him from fathering children, nor does unilateral excision of a testis

necessarily decrease virility. The nurse reminds the patient about the

importance of perform-ing TSE and keeping follow-up appointments with the

physician. The patient is also encouraged to participate in health promotion

and health screening activities.

HYDROCELE

A hydrocele is a collection of fluid,

generally in the tunica vagi-nalis of the testis, although it may also collect

within the sper-matic cord. The tunica vaginalis becomes widely distended with

fluid. Hydrocele can be differentiated from a hernia by transillu-mination; a

hydrocele transmits light, whereas a hernia does not. Hydrocele may be acute or

chronic. Acute hydrocele may occur in association with acute infectious

diseases of the epididymis or as a result of local injury or systemic

infectious diseases, such as mumps. The cause of chronic hydrocele is unknown.

Usually, therapy is not required. Treatment

is necessary only if the hydrocele becomes tense and compromises testicular

circu-lation or if the scrotal mass becomes large, uncomfortable, or

em-barrassing. In the surgical treatment of hydrocele, an incision is made through

the wall of the scrotum down to the distended tu-nica vaginalis. The sac is

resected or, after being opened, is su-tured together to collapse the wall.

Postoperatively, the patient wears an athletic supporter for comfort and

support. The major complication is hematoma in the loose scrotal tissues.

VARICOCELE

A varicocele

is an abnormal dilation of the veins of the pampini-form venous plexus in the

scrotum (the network of veins from the testis and the epididymis that

constitute part of the spermatic cord). Varicoceles usually occur in the veins

on the upper portion of the left testicle in adults. In some men, a varicocele

has been associated with infertility. Few, if any, subjective symptoms may be

produced by the enlarged spermatic vein, and no treatment is required unless

fertility is a concern. Symptomatic varicocele (pain, tenderness, and

discomfort in the inguinal region) is corrected surgically by ligat-ing the

external spermatic vein at the inguinal area. An ice pack may be applied to the

scrotum for the first few hours after surgery to relieve edema. The patient

then wears a scrotal supporter.

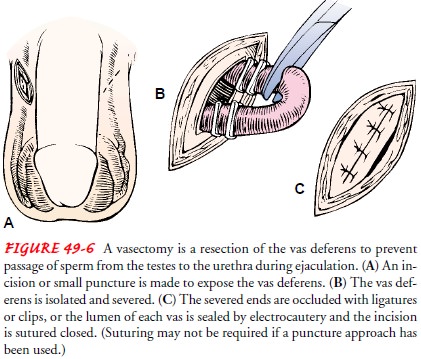

VASECTOMY

Vasectomy, or male sterilization, is the ligation and transection ofpart of the

vas deferens, with or without removal of a segment of the vas deferens. To

prevent the passage of the sperm from the testes, the vas deferens is exposed

through a surgical opening in the scrotum or a puncture using a sharp, curved

hemostat (Fig. 49-6). The severed ends are occluded with ligatures or clips, or

the lumen of each vas deferens is sealed by cautery. The spermatozoa, which are

manufactured in the testes, cannot travel up the vas deferens after this

surgery.

Because

seminal fluid is manufactured predominantly in the seminal vesicles and

prostate gland, which are unaffected by va-sectomy, no noticeable decrease

occurs in the amount of ejacu-late even though it contains no spermatozoa.

Because the sperm cells have no exit, they are resorbed into the body. This

procedure has no effect on sexual potency, erection, ejaculation, or

produc-tion of male hormones and provides no protection against sexu-ally

transmitted diseases.

Couples who were worried about pregnancy

resulting from contraceptive failure often report a decrease in concern and an

in-crease in spontaneous sexual arousal after vasectomy. Concise and factual

preoperative explanations may minimize or relieve the pa-tient’s concerns

related to masculinity. Although a relationship between vasectomy and

autoimmune disorders and prostatic can-cer has been suggested, there is no

clinical evidence of either.

The

patient is advised that he will be sterile but that potency will not be altered

after a bilateral vasectomy. As with any surgi-cal procedure, a surgical

consent form must be signed. On rare occasions, a spontaneous reanastomosis of

the vas deferens oc-curs, making it possible to impregnate a partner.

Complications of vasectomy include scrotal

ecchymoses and swelling, superficial wound infection, vasitis (inflammation of

the vas deferens), epididymitis or epididymo-orchitis, hematomas, and spermatic

granuloma. A spermatic granuloma is an inflammatory response to the collection

of sperm leaking into the scrotum from the severed end of the proximal vas

deferens. This can initiate re-canalization of the vas deferens, making

pregnancy possible.

Nursing Management

Ice

bags are applied intermittently to the scrotum for several hours after surgery

to reduce swelling and to relieve discomfort. The nurse advises the patient to

wear cotton, Jockey-type briefs for added comfort and support. He may become

greatly con-cerned about the discoloration of the scrotal skin and superficial

swelling. These are temporary conditions that occur frequently after vasectomy

and may be relieved by sitz baths.

Sexual

intercourse may be resumed as desired, although fer-tility remains for a

varying time after vasectomy until the sper-matozoa stored distal to the

severed vas deferens have been evacuated. Other methods of contraception should

be used until infertility is confirmed by an examination of ejaculate. Some

physicians examine a specimen 4 weeks after the vasectomy to determine

sterility; others examine two consecutive specimens 1 month apart; and still

others consider a patient sterile after 36 ejaculations.

Vasovasostomy (Sterilization Reversal)

Microsurgical techniques are used to reverse

a vasectomy (vaso-vasostomy), thus restoring patency to the vas deferens. Many

men have sperm in their ejaculate after a reversal, and 40% to 75% can

impregnate a partner.

Banking Sperm

Storing fertile semen in a sperm bank before

a vasectomy is an op-tion for men who face an unforeseen life event that may

cause them to want to father a child at a later time. In addition, if a man is

about to undergo a procedure or treatment (eg, radiation ther-apy to the pelvis

or chemotherapy) that may affect his fertility, sperm banking may be

considered. This procedure usually re-quires several visits to the facility

where the sperm is stored under hypothermic conditions. The semen is produced

by masturba-tion and collected in a sterile container for storage.

Related Topics