Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Clinical management : Pre operative evaluation

Common disorders - Anesthesia Clinical management

Common disorders

We

encounter many patients with pre-existing medical conditions. Anesthetic and

operative procedures constitute a physiologic trespass with which the patient

can deal better, if not simultaneously challenged by correctable derangements

that sap his strength and threaten his homeostasis. Ideally, the surgeon would

already have addressed these questions. However, that is not always the case,

and the anesthesiologist needs to assess the medical condition of the patient.

The answers to the question, “Is the patient in the optimal condition to

pro-ceed with anesthesia and operation?” are not always clear-cut. For example,

a patient with transient ischemic attacks is scheduled for a carotid

endarterec-tomy. The patient also has coronary artery disease and unstable

angina. Should we risk the possibility of a stroke by first putting the patient

through a heart operation, or should we risk a myocardial infarction by first

doing a carotid endarterectomy? Consultations with other experts help in

resolving such difficult issues.

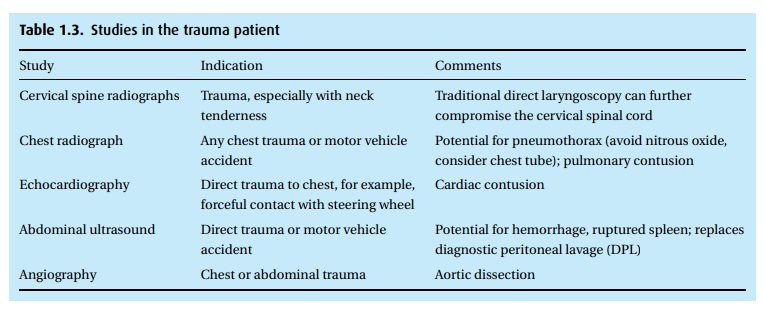

Trauma emergency

Rapid

assessment of the airway and fluid status precedes, or coincides with, the most

urgent: stemming of hemorrhage. Once we have secured an airway and established

a route for administering fluids, we can contemplate anesthe-sia, realizing

that a patient in hemorrhagic shock will tolerate and require very little

anesthesia. The mechanism of the trauma may suggest additional studies (Table 1.3).

Diabetes

We focus

on the many end-organ effects of diabetes, as well as the patient’s glu-cose control

(HgbA1c). Those with poor control should be considered for pre-admission.

Pre-operative studies should include assessment of metabolic, renal, and

cardiac status. In general, diabetic patients should be scheduled early in the

day.

Because

of the 30% incidence of gastroparesis in this population, diabetics are often

pretreated with metoclopramide to speed gastric emptying and are induced with a

‘rapid sequence induction’ (see General anesthesia). Intra-operative

man-agement aims to match insulin requirements, recognizing the fasting state

and the effects of surgical stress.

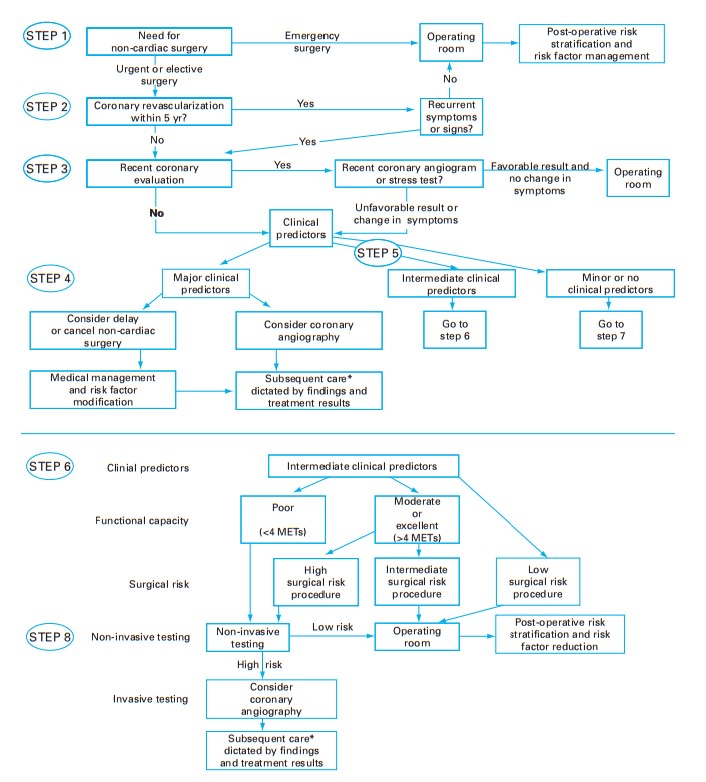

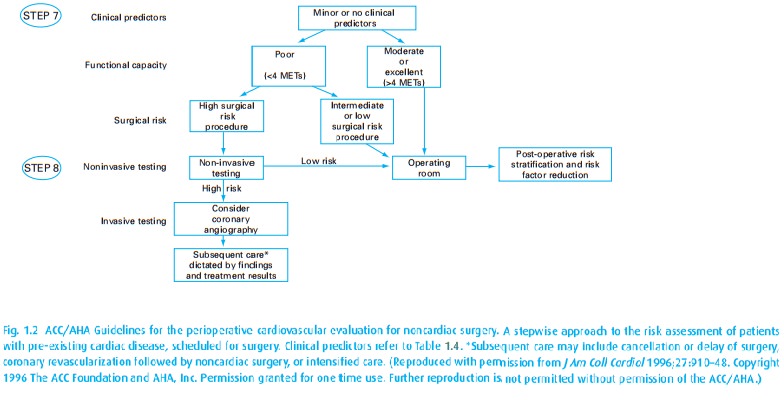

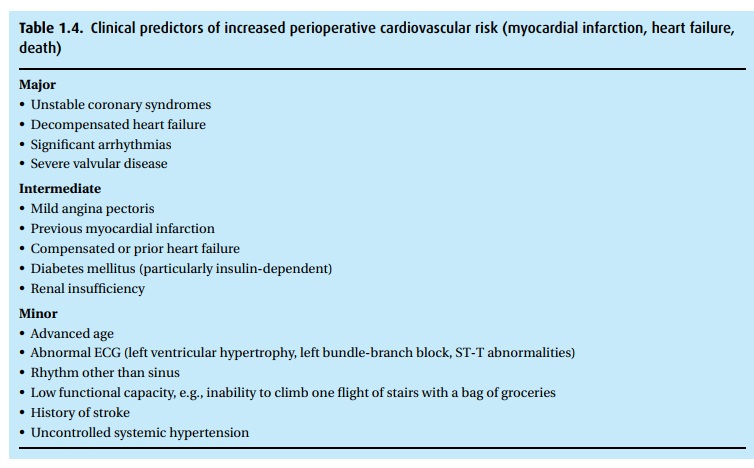

Coronary artery disease

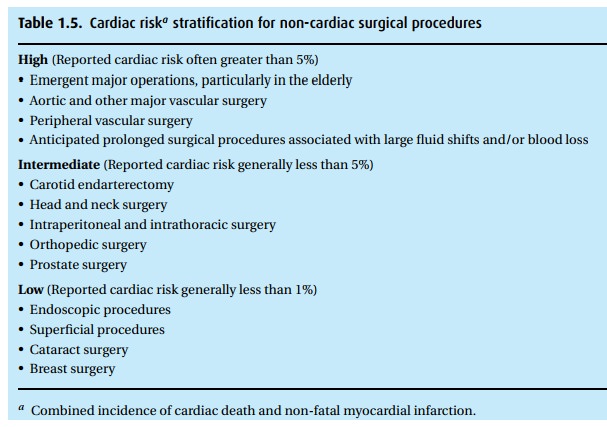

In 2002,

the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA)

published updated guidelines for the perioperative cardiovascular evaluation of

patients for non-cardiac surgery. These so-called “Eagle criteria” should be

applied only when the results are likely to impact care. We should always ask

the patient about their exercise tolerance; the ACC/AHA recommendations attempt

to quantify this by using metabolic equivalents (METs), which enables us to

classify patients on a scale of 1 (take care of yourself around the house) to

10+ (participate in strenuous sports). A useful dividing line is 4

METs (climb a flight of stairs). In general, patients unable to do more than 4

METs represent a group at high risk of cardiovascular complications. The

algorithm in Fig. 1.2helps in assigning

risks and identifying those patients who require additional cardiac evaluation.

In addition to their functional capacity, the algorithm incorporates medical

status (Table 1.4) and the procedure planned

(Table 1.5).

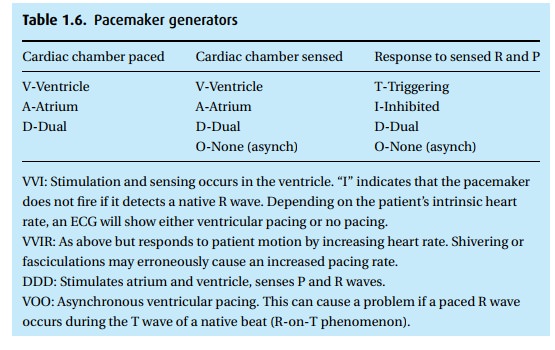

Pacemaker/AICD

Pacemakers

are life saving for many patients with heart rhythm disturbances. There are

many types available, with a range of functionality (see Table 1.6). The addition of an automatic internal

cardiac defibrillator goes one step further. Unfortunately, these life-saving

devices may fail to function properly in the presence of electrical devices,

e.g., electrocautery. Many patients carry a card identifying the pacemaker make

and model. Some can also provide a report from a recent electronic

interrogation that specifies proper function and remain-ing battery life. More

often than not, we do not have that information. A chest radiograph can reveal

pacer make and model, as well as lead location. In symp-tomatic (lightheaded

spells, palpitations, hypotension) or in pacer-dependent patients, a pacemaker

interrogation (by a specialist with proprietary communi-cation equipment) may

be necessary. If this is not an option, a current ECG might be helpful, if it demonstrates pacer spikes in appropriate

locations.

Pulmonary disease

The

patient with pre-operative pulmonary disease faces risks of intra-operative and

post-operative pulmonary complications including pneumonia, bron-chospasm,

atelectasis, respiratory failure with prolonged mechanical ventilation, and

exacerbation of pre-existing lung disease. The risk of these complications

depends on both the patient and the procedure.

·

Chronic pulmonary disease Both chronic obstructive pulmonary disease(COPD)

and asthma can increase the risk. Therefore, well before anesthesia and surgery

we should treat the patient to bring him into the best possible condition,

given his lung disease.

·

Smoking Even without evident lung disease, smoking

increases the risk of pul-monary complications up to four times over that or

non-smokers. Eight weeks of smoking cessation isf required to reduce that risk,

though carboxyhemoglobin will virtually vanish after only 24 smoke-free hours.

·

General health There are general risk indices that predict

pulmonary compli-cations well. In fact, exercise tolerance alone is an

excellent predictor of post-operative pulmonary complications.

·

Obesity Obese patients present more airway management

difficulties for severalreasons: (i) mechanical issues related to optimal

positioning; (ii) redundant pharyngeal tissue complicating laryngoscopy; (iii)

many suffer from obstructive sleep apnea (and its sequelae: pulmonary

hypertension/cor pulmonale); and (iv) in obese patients it can be extremely difficult

or impossible to mask–ventilate the lungs due to the weight of the chest wall.

Obesity also increases the risk for thromboembolic phenomena. Post-operatively,

however, obesity has not proven to increase the risk of pulmonary

complications.

·

Surgical site Proximity of the surgical site to the diaphragm

is the single mostimportant predictor of pulmonary complications. Thoracic and

upper abdom-inal operative sites confer a 10–40% incidence. This can be reduced

perhaps 100-fold with laparoscopic techniques.

·

Surgery duration Operations lasting<3 hours are associated with fewercomplications.

·

Intra-operative muscle relaxants Pancuronium, specifically, has been

associatedwith an increased incidence of pulmonary complications; this is

related to its long half-life and risk of residual muscle weakness.

·

Results of pre-operative testing Routine pre-operative pulmonary function

tests(PFTs) are not indicated, unless the patient is undergoing lung resection.

If available, however, the risk of complications increases when the forced

expira-tory volume in 1s (FEV1) or forced vital capacity (FVC) are <70% predicted, or when the FEV1/FVC

is <65%

Asthma

Pre-operatively,

our goals are to reverse bronchospasm and inflammation, pre-vent an asthma

exacerbation, clear secretions, and treat any infection. We specif-ically ask

about any increased inhaler use, recent hospitalizations or Emergency

Department visits for bronchospasm, a recent change in sputum amount or color,

or a recent cold. All of these factors increase the risk of peri-operative

bron-chospasm. If the patient is scheduled for thoracic or upper abdominal

surgery (with a very high risk of pulmonary complications), spirometry can

identify patients at greatest risk.

Glucocorticoids

may be helpful in those patients who do not respond ade-quately to 2

agonists. Patients who are steroid dependent will often have suppressed adrenal

cortical function and require supplemental steroids in the peri-operative

period.

Chronic renal failure

Chronic

renal failure (CRF) involves both the excretory and synthetic functions of the

kidney. When the kidney fails to regulate fluids and electrolytes, the net

result is acidosis, hyperkalemia, hypertension, and edema. Meanwhile, the lack

of syn-thetic function results in anemia (due to decreased production of

erythropoietin) and hypocalcemia from a lack of active vitamin D3

(this also leads to secondary hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphatemia, and renal

osteodystrophy). Azotemia can cause platelet dysfunction.

Medications

that are renally excreted will be affected by CRF, and most should be avoided.

In particular, meperidine (pethidine, Demerol®) should not be given as its

metabolite (normeperidine) can accumulate and cause seizures. The pre-ferred

muscle relaxant is one that does not depend on renal function for its

metabolism (atracurium, cis-atracurium

for surgical relaxation).

We check

electrolytes on these patients pre-operatively and prefer they undergo dialysis

within the preceding 24 hours. We must resist the temptation to hydrate a patient

who is intravascularly ‘dry’ following dialysis, as they cannot excrete excess

fluids. Replacement fluids should not contain potassium (normal saline is

preferred over Ringer’s lactate) as these patients are at risk for

hyperkalemia. CRF patients are also at increased risk for coronary artery and

peripheral vascular disease.

Related Topics