Chapter: Essential Anesthesia From Science to Practice : Clinical management : Pre operative evaluation

Anesthetic choice - Anesthesia Clinical management

Anesthetic choice

In

addition to the above assessment, the anesthetic plan must consider the wishes

of both patient and surgeon, as well as our

individual skill and experience. Does the patient have special requests that

need to be taken into account? For example, some patients would like to be

awake (maybe the President so he doesn’t have to pass control of the US to the

Vice-President), others asleep, and others do not want “a needle in the back.”

Some

patients present special problems, for example Jehovah’s Witnesses who do not

accept blood transfusions, based on their interpretation of several pas-sages

in the Bible (for example Acts 15:28, 29). A thoughtful and compassion-ate

discussion with the patient usually finds the physician agreeing to honor the

patient’s wishes, an agreement that may not be violated. The caring for

children of Jehovah’s Witnesses brings an added concern and may require ethics

consultation and perhaps even referral to a court. Again, these issues are best

brought out days prior to surgery at a scheduled pre-anesthetic evaluation.

Numerous

studies have failed to demonstrate that a particular inhalation anes-thetic,

muscle relaxant, or narcotic made for a better outcome than an alternative.

Yet, over the years, actual or perceived differences and conveniences have

caused some drugs to disappear and others to establish themselves. Given an array

of options, we can often consider different approaches to anesthesia, which we

can discuss with the patient. We should always recommend the approach with

which we have the greatest experience and which we would select for ourselves

or a loved one.

The choices

depend on several factors, first of which is the surgical procedure. For

example, the site of the operation, e.g., a craniotomy, can rule out spinal

anesthesia. The nature of the operation, e.g., a thoracotomy, can compel us to

use an endotracheal tube. For the removal of a wart or toenail or the lancing

of a boil, we would not consider general anesthesia – unless the patient’s age

or psychological condition would make it preferable. The preferences of the

surgeon might also be considered.

This

introduces the patient’s condition as a factor in the choice of anesthesia. For

example, a patient in hemorrhagic shock depends on a functioning sym-pathetic

nervous system for survival and therefore cannot tolerate the sympa-thetic

blockade induced by spinal or epidural anesthesia. A patient with an open eye

can lose vitreous if the intra-ocular pressure rises, as might occur with the

use of succinylcholine. Vigorous coughing at the end of an eye operation might

do the same and must be avoided. Respiratory depression and elevated arterial

carbon dioxide levels can increase intracranial pressure with potentially

devas-tating effects in patients with an intracranial mass or hemorrhage. In

obstetri-cal anesthesia, mother and

child have to be considered. Here, we do not wish to depress uterine

contraction nor cause prolonged sedation of the newborn child. Some agents used

in anesthesia rely on renal excretion, others on hepatic metabolism, thus

tilting our choice of drugs in patients with renal or hepatic insufficiency.

In the

majority of patients, however, it makes little difference what we pick. We

could choose one or the other technique for general anesthesia, using one or

the other intravenous induction drug and neuromuscular blocker, and relying on

one or the other inhalation anesthetic. We can supplement such a technique with

one of a number of narcotic drugs available to us, or we can use total

intravenous anesthesia. When we use general anesthesia, we can intubate the

patient’s trachea and let the patient breathe spontaneously, or we can

artificially ventilate the patient’s lungs. Instead of an endotracheal tube, we

have available the laryngeal mask airway, preferably used in spontaneously

breathing patients or, in the very old-fashioned approach, we might use only a

face mask.

In many

instances, we have options, the choice of which will be influenced by our own

experience and expertise. For example, anesthesiologists with extensive

experience in regional anesthesia will select that technique in preference to

gen-eral anesthesia in cases where either technique can prove satisfactory for

patient and surgeon. Examples include many orthopedic operations or procedures

on the genitourinary tract.

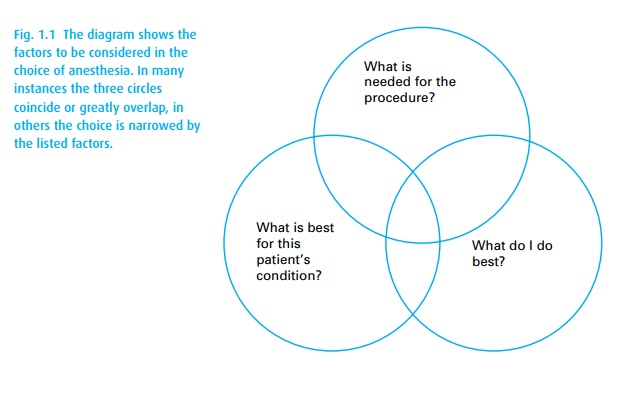

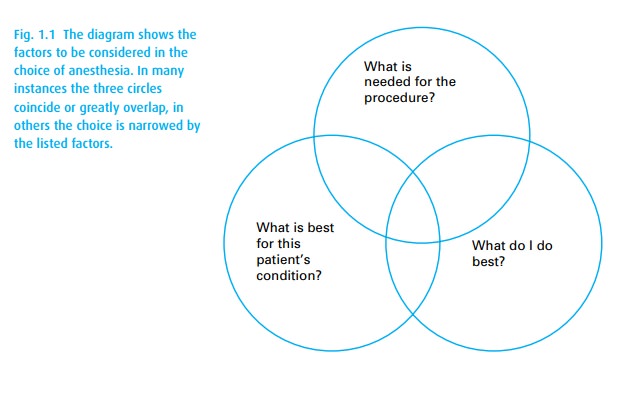

In

summary, many factors can influence the choice of anesthesia. In the major-ity

of patients, however, we have the luxury of making the choice influenced by our

own preference and routine (Fig. 1.1).

Related Topics