Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Stocking of Open Waters and Ranching

Coastal and inland seas - Open water stocking

Open-water stocking

Coastal and inland seas

The stocking or repopulation described earlier was restricted largely to

fresh-water environments. The limitations of human control on aquatic

populations in the sea areas and the immensity of efforts required to over-come

them have discouraged some of the early attempts to enhance marine stocks. Probably

the first large-scale attempt to stock the sea was the one started in 1950 with

the cod (Gadusmorhua) larvae in the

Oslofjord in Norway,which was eventually abandoned in 1971 as the benefits of

stocking could not be demonstrated. It is only in recent years that more

organized intensive research started to examine more closely the viability of

stocking this species.

The most organized and ambitious programme of sea stocking today takes

place in Japan, particularly in the Seto Inland Sea area.

It is an effort to establish what is referred to as culture-based

fisheries, and forms part of a policy to increase the marine resources of the

country for future harvests. It is carried out by fishery cooperatives and is

promoted by

both the national and prefectural governments. Besides stocking young

ones, the programme includes environmental improvements, including improvements

to the sea bottom, to facilitate the interchange of sea and fresh water, the

creation of special nursery and growing areas, provision of shelters, measures

to reduce wave velocity, etc. The term ‘fish farming’ is used in Japan to

denote this type of programme, which is considered to be a stage intermediate

between ordinary fishing from natural resources and extensive fish culture.

Although the breeding techniques are intensive, the grow-out takes place in the

open sea, with feeding on natural food.

Probably the most important species presently stocked is the kuruma

shrimp, Penaeus japonicus. Several

millions of fry ofabout 1cm length are released every year. After about four or

five months, the shrimps have grown to the commercial size of 11–12cm. The

survival rate of the released fry depends very much on the techniques of

release, environmental conditions during growth and fishing conditions.

Survival rates of 0.1–10 per cent have been reported. As a result of

considerable research, several measures are now being adopted to increase the

survival rate of released shrimps. Being a typical burrowing species, the

released fry burrow into the sub-strate and become more or less sedentary

within a well-defined area, until they gradually move to offshore areas. The

hatchery-reared juveniles acquire this burrowing habit only when about 10mm in

size, as against 7–9mm in the natural stocks. This has led to the practice of

releasing them only after they reach 10mm in size. Selection of the stocking

site is an equally important factor. The most suitable sites are usually

intertidal sand flats between the mean low-water neap tide and mean sea level,

where there are shallow pools which will only contain a few metres of water at

high tides. Hatchery-reared shrimp fry are planted at low tide into such pools,

which may sometimes be fenced in for an initial period.

It has been shown experimentally that initial severe mortality occurs

within 24 hours after release of the fry. Even though a combination of factors

such as unfavourable temperature, salinity, oxygen content or turbulence can

kill the fry, predation by invertebrates such as the hermitcrab (Pagurus dubius) and the gastropod Niothalivescens and by intertidal

species of fish such asthe goby (Gobius

gymnauchen) is the main cause of mortality during this period. While the

invertebrates attack the shrimp fry only when their activity is impaired by

adverse environmental conditions, such as low salinity or high temperatures,

the predation by gobies is severe, even when the fry are very active.Almost 60

per cent of the initial mortality is ascribed to preda-tion by fish. To reduce

this initial mortality the fry are released first into a fenced enclosure or an

artificial lagoon in the intertidal area. Since such fenced enclosures can be

subject to fre quent damage, an artificial tide-land is devised to serve as

stocking site.The main objective is to control the environmental conditions in

order to prevent foraging by predatory fish and yet to permit a sedentary life

for the hatchery-reared shrimp fry.

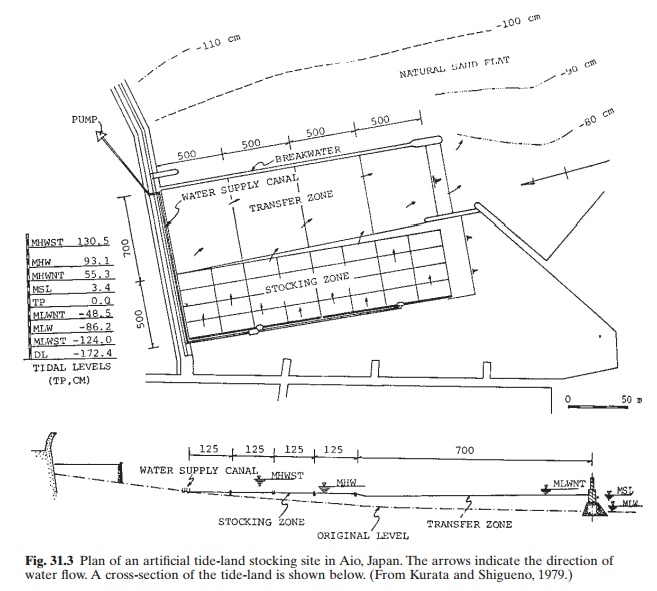

The artificial tide-land (fig. 31.3) consists of (i) a stocking zone at

the mean high-water neap tide level, inclined seaward at a slope of 1/200 and

divided into rectangular blocks by concrete septa buried in the substrate,

leaving the upper 5cm above sand, and (ii) a transfer zone at mean sea level,

linking the stocking zone to the natural sand flats fronting the tide-land. The

two zones are considered necessary as it has been observed that the

initial loss is much less at higher elevations of about 40cm above mean sea

level if the level of water in the pool is maintained by pumping. However, for

free dispersion of fry as they grow in size they would have to be transferred

to a transfer zone at a lower level. If the area is exposed at low tide, a pump

is used to inundate it to a depth of less than 5cm.The fry are released into

the stocking zone at the rate of about 100 per m2. As they grow, the fry move from

the stocking zone to the transfer zone and then to the natural sand flats, to

grow into adult shrimps. By the time they attain an average body length of

about 25– 30mm, in about two to three weeks after release, the majority of the

survivors will have left the stocking zone for deeper waters. The stocking zone

can then be used again for further release.

It is obviously very difficult to determine conclusively the survival

rate and cost benefit ratio of kuruma shrimp release, when the commercial

fisheries are also dependent on natural recruitment in the area. If increased

catches are observed they can also be ascribed to natural fluctuations of the

fisheries. Despite all this, there appears to be a general agreement among

certain sectors of the public, as well as among shrimp fishermen in Japan, that

the stocking of kuruma is not only capable of substantially increasing the

local shrimp production, but can also support a considerable fishery, if

adequate numbers of fry are stocked according to an organized plan.

Although attempts have been made to stock the seas with shrimp larvae in

certain other areas, as on the Kuwaiti coast, the only really successful case

of developing a fishery by stocking hatchery-reared juveniles of shrimps

appears to be in Italy in the lagoons of Lessina and Venice. Introduced Penaeus japonicus has been propagated in

hatcheries and, as a result of stocking, small populations of the species have

developed and are commercially exploited.The rearing and release of the lobsterHomarus

gammarus has a

long history in Norway, starting from around 1928. It is

now possible to produce seed stock in hatcheries, using low-intensity lighting,

adequate feeding, and continuous sorting according to size. Larvae can be grown

individually in specially designed partitioned troughs up to the juvenile

stage, to avoid cannibalism. Preliminary experiments in ranching the American

lobster (H. americanus) have been

conducted in Massachusetts, USA, using concrete-filled tyres as shelters

(Hruby, 1979), but because lobsters are continually moving, stable populations

could not be established. It is reported that half a million young lobsters are

released on the Massachusetts coast every year. Experimental stocking is being

done also in the state of Maine (USA), Norway and France.

Many of the on-bottom mollusc culture methods described are essentially

stocking operations to increase populations in foreshore areas and to develop

new resources. In northern Japan fisheries of the common scallop (Pectinopecten) have been enhanced by the

collection and stocking of natural seed and by the eradication of predators

such as starfish and sea urchins. Attempts have also been made to improve the

production of abalones, by planting hatchery-reared seed and developing beds of

seaweeds to increase their food resources. Preliminary experiments in the

repopulation of the queen conch (Strombus

gigas) have been made in some of theislands of the Caribbean area. It is

possible to grow young conch from egg cases hatched under hatchery conditions.

However, without any control of fishing for the released juveniles, their

survival rates cannot be assessed.

As mentioned earlier, several efforts have been made to stock the seas

with hatchery-reared fish species. Other than anadromous species, which are

discussed, none of the others appear to have proved successful

in enhancing populations or developing new ones. Progress is being made in the

release of the red sea-bream (Pagrus

major) in Japan, and the possibility of repopulating cod is being

reexamined in Norway.

Related Topics