Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Dental and Periodontal Infections

Chronic Periodontitis

CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS

Both gingivitis and chronic periodontitis are now believed to be caused by certain bacte-ria in the dental plaque that lie in close proximity to the necks of the teeth and marginal gingival tissues. Thus, subgingival plaque found within the gingival crevice or the sulcus around the necks of the teeth is thought to house the etiologic agent(s). The characteristic histopathologic picture of gingivitis is of a marked inflammatory infiltrate of polymor-phonuclear leukocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells in the connective tissue that lies immediately adjacent to the epithelium lining the gingival crevice and attached to the tooth. Collagen is lost from the inflamed connective tissue. There does not seem to be any direct invasion of the gingival tissues by large numbers of intact bacteria, at least in the early stages of the disease.

It has been proposed that tissue destruction is mediated by bacterial substances that pass through the epithelial barrier and cause either direct or indirect injury. Bacterial products that could cause direct injury to the tissues include toxins, such as endotoxin and leukotoxins, and enzymes, such as hyaluronidase and collagenase. Several mecha-nisms for indirect injury of the periodontal tissues have been proposed. These hypotheses include initiation of an unresolvable inflammatory response with excessive release of the lysosomal contents from polymorphonuclear leukocytes; activation of complement, which further magnifies the inflammatory response; and development of a host of hu-moral and cell-mediated immune responses, which can also magnify the inflammatory re-action as well as lead to tissue destruction. A complex pattern of interactions between various released chemokines and cytokines (eg, interleukins 1, 4, 5, 6, and 12; tumor necrosis factor-α ; interferons- α and β; transforming growth factor-α ; and prostaglandin E2) and their target cells have been implicated in the modulation of the host response to the periodontal pathogens, some of which may lead to tissue destruction. Many oral bac-teria have been found to contain potent polyclonal -lymphocyte activators, leading some investigators to propose that periodontal pathogens release these substances into lesions. Polyclonal -cell activation could promote an exaggeration of the inflammatory response and further tissue injury through enhanced antibody and cytokine production. Regardless of the mechanisms of tissue destruction, the true source of the disease, namely the causative bacteria, remains outside the gingival tissues in supra- and subgingival plaque and is therefore often resistant to the body’s defense mechanisms. There is evidence that some bacteria do invade the gingival tissues, especially in the more aggressive forms of periodontitis, and this invasion may constitute a pathogenic mechanism. Nevertheless, the origin of these bacteria is the dental plaque, and so the disease continues to progress un-less the dental plaque is removed and the involved tooth is kept plaque-free. If these mea-sures are taken, chronic gingivitis can resolve completely and the tissues return to normal.

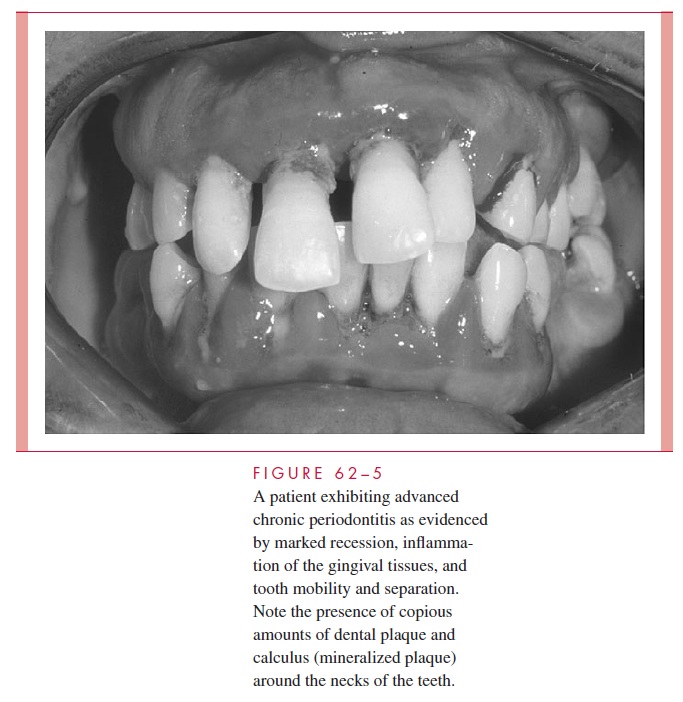

As the disease progresses, a point may be reached at which the alveolar bone around the necks of the teeth is resorbed; the condition is then no longer termed gingivitis, but peri-odontitis. With resorption of the bone, the attachment of the periodontal ligament is lost and the gingival sulcus deepens into a periodontal pocket. Periodontitis is not considered to be a reversible disease in that the lost alveolar bone and periodontal ligament do not regenerate with cessation of the inflammation, even though further progression may be halted. If unchecked, bone resorption progresses to loosening of the tooth, which may ultimately be exfoliated. Figure 62 – 5 shows a case of advanced chronic periodontitis in which the gingi-val tissues are inflamed, gross deposits of plaque and calculus around the necks of the teeth are apparent, and the teeth have spread apart and extruded due to the major loss in their periodontal attachment. Occasionally, the neck of a periodontal pocket becomes constricted, the bacteria proliferate causing an acute inflammatory response in the occluded pocket, and a periodontal abscess results. This acute exacerbation requires drainage in the same way as abscesses elsewhere for the patient to obtain symptomatic relief.

Gingivitis develops within 2 weeks in individuals who fail to practice effective tooth cleansing. It is not known whether particular species of plaque bacteria are responsible for gingival inflammation, but among those suspected of pathogenicity in the case of

Manyof these organisms produce periodontal disease in monoinfected animals. It has been sug-gested recently that the disease may be caused by the combined effects of two or more of these pathogens at a site, rather than there being only one species of microorganism re-sponsible for the destructive lesion.

There is some evidence that the causative agents in aggressive forms of periodontitis may differ from those associated with chronic marginal disease. In the condition known as localized aggressive periodontitis, a small capnophilic (carbon dioxide – requiring) Gram-negative rod (Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans) has been indicted based on studies of the flora of disease sites. A virulence factor found in those strains of A. actino-mycetemcomitans that are associated with this disease is the production of a leukotoxinby the bacteria. In addition, it has been found that a significant proportion of patients with this condition demonstrate high serum antibody titers to A. actinomycetemcomitans. Also of interest is the fact that many of these patients have neutrophil chemotactic or phago-cytic defects.

Related Topics