Chapter: Aquaculture Principles and Practices: Catfishes

Channel catfish

Channel catfish

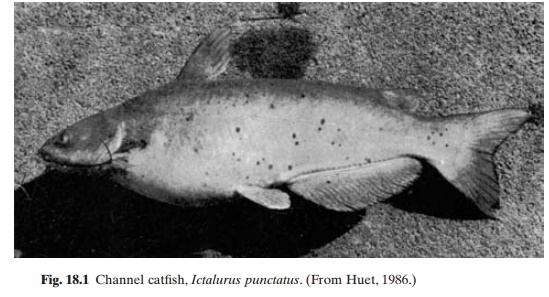

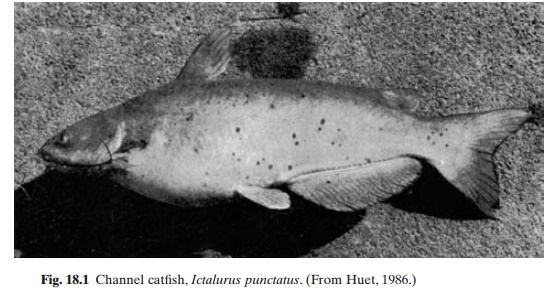

The most important aquaculture species of catfish in the USA is the channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus, family Ictaluridae) (fig. 18.1),although the white catfish (I. catus), which are more tolerant to crowding, higher temperature and low oxygen levels, and the blue catfish (I. furcatus), which grow more uniformly and dress-out better, also have farming potential. Among the many catfish cultured in Asia, the most important is Clarias batrachus, although the slower-growing allied species, C. macro-cephalus,has a higher consumer preference.Thespecies of catfish that has received greater attention in Africa is the so-called African catfish C. lazera. This species is synonymous with the sharp-tooth catfish, C. gariepinus, but the usage of lazera as species name is continued herein. Recently, efforts have also been directed towards developing a technology for the culture of the brackish-water catfish Chrysicthys spp. Catfish farming in southeastern Europe is based on the sheatfish or wels, Silurus glanis.

Culture systems

Pond culture is the most common culture system of catfish in all parts of the world, and most of the present-day production comes from small- and large-scale pond farms. Though more than one species of catfish may be reared in the same pond, polyculture of the type employed in carp farming is seldom practised. Exceptions are the small-scale rearing of Pangasius with tawes (Puntius gonionotus) andsepat siam (Trichogaster pectoralis) in Thailand, and the grow-out of yearlings of sheatfish in carp ponds. The double-cropping system of channel catfish with rainbow trout in the south-ern USA has already been described in the previous section.

In predominantly catfish-farming areas, preference is usually for intensive farming systems. The hardy nature of the species makes high-density culture possible. Nevertheless, as will be discussed later, excessive stocking densities and very intensive feeding have created several management problems in some areas, such as Thailand.

Raceway culture is one of the intensive systems of catfish farming employed in the USA. Raceways constructed of concrete, asphalt, concrete blocks or earth are used. The degree of production intensity depends largely on the abundance of the water supply. Smaller raceways with water supplies of high volume and high velocity are used for highly intensive production, whereas larger raceways with a lower water flow are utilized for semi-intensive systems of production. A recent development is the use of circular and linear tanks for growing fish to market size.

The catfish Pangasius has been cultured from ancient times in floating bamboo cages in Kam-puchea and Thailand. This system of culture is now carried out in Europe and the USA as well, using new and improved types of cages and feeds. However, cage culture production of catfish in any of these areas is only a small percentage of that of ponds and raceways.

A culture system of some importance in the USA consists of the development and management of what are called fee-lakes, pay-lakes orput-and-take fishing. Operators of such establishments produce their own fingerlings for stocking lakes or ponds, or buy fingerlings from other producers. Recreational fishermen are allowed to fish in these waters for a fee, based on the quantity of fish caught or the duration of recreational fishing.

Propagation and grow-out

Brood stock

Normally brood fish of channel catfish are about three years old and weigh at least 1.36kg, and a female of that size can be expected to spawn 6000–9000 eggs. Larger brood fish of up to 4.5kg are also used, but the smaller ones are easier to handle. Though brood fish can be obtained from streams or lakes, farmers prefer cultured brood fish grown on a diet rich in animal protein in a clean and healthy environment. In the absence of strains developed through selective breeding, farmers generally choose large individuals that look healthy. To reduce inbreeding depression, it is considered advisable to introduce some brood fish from outside sources every year. New brood stock, as well as those that have already been spawned, are reared in brood ponds.

The size of the stocking ponds and the stocking density depend on the size of individual fish

and the rate of growth required. Smaller fish of about 1–1.4kg are stocked at the rate of 340–450kg/ha and larger fish at a rate of about 900kg/ha. The natural fool produced in a well-fertilized pond (including minnows, tadpoles and other forage organisms) can sustain about 340kg/ha, but supplemental feeding is needed at higher stocking rates. Daily feeding at about 3.4 per cent of body weight is recommended, depending on the availability of natural food. It is a common practice to feed maturing fish once a week, during late winter and early spring.

Additional food consisting of fresh or frozen meat, fish or beef liver, beef heart or other low-priced meat products is given at the rate of 10 to 15 per cent of the body weight. These items of diet are believed to meet the additional needs of minerals and vitamins of brood fish during gonadal development. Feeding is generally stopped if the water temperature goes below 7°C, though some culturists recommend a low-level feeding of 0.5 per cent of the body weight every four to five days during this period. The required sex ratio of brood stock depends on the method of spawning, but generally a 1:1 ratio is considered suitable.

The sexes can be differentiated by the secondary sexual characteristics developed during the spawning season. The female develops a well-rounded abdomen and the genital pore becomes raised and inflamed. The head of the male is wider than the body, with darker pigments under the lower jaw and on the abdomen. A large protruded genital papilla is another distinguishing characteristic.

Spawning and fry production

Channel catfish can be spawned in ponds, special pens and in aquaria or similar containers. Provision of a suitable nest is the major requirement for pond spawning as the natural nesting sites, such as holes in banks or sub-merged stumps in the natural habitats, may not be available in ponds. Shallow ponds of about 0.4ha usually serve as spawning ponds, but bigger ponds of up to 2ha are also sometimes used. Spawning nests may be made of nail kegs, wooden boxes, hollow logs, large milk cans, concrete tiles, metal drums, etc.The number of nests needed is dependent on whether the fertilized eggs are allowed to hatch in the spawning pond itself or are to be removed and hatched indoors in hatchery troughs. It is possible to use fewer nests than pairs of fish, as not all fish spawn at the same time, and so one nest for each two pairs of fish is considered a good rule of thumb to follow. The nests are placed around the edge of the pond at depths varying from 15 to 150cm water, with the open end facing the centre of the pond. The number of brood fish to be introduced depends on whether the eggs are to hatch out in the pond or will be removed for hatching indoors. If the hatching takes place in the pond, a stocking density of 50 females per ha is recommended, whereas if the spawn is to be removed for hatching the density can be raised to 125 females per ha.

Channel catfish spawn in late spring and summer, depending on the strain and the geographic region, at a temperature between 21 and 29°C. After introducing the brood fish in the ponds, the nests are checked regularly to see whether spawning has taken place. As too frequent checking may disturb the spawners, checking only every three days is recommended. Following spawning, the male catfish guards the eggs during incubation and fans them with his fins to keep a current of well oxygenated water flowing over them.

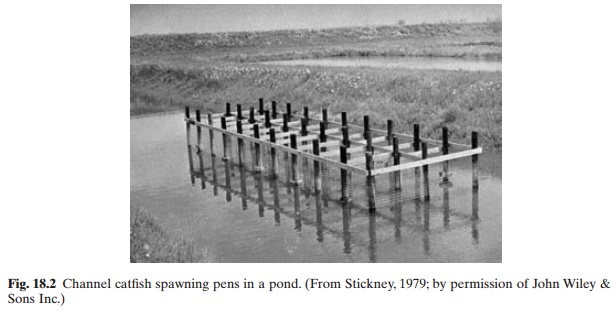

Pen spawning is a relatively more controlled method of propagation (fig. 18.2), where it is possible to ensure mating between a selected pair of brood fish, which is not possible in ponds. Pens are usually placed in ponds, but flowing streams are also suitable. Different sizes of pens are used, but generally they are not larger than 2m x 3m, the depth being less than 1m. They are constructed of wood and welded steel wire mesh, (2.5cm by 5cm mesh) and are embedded in the pond bottom with about 0.3–0.6m of the pen above the water. A spawning nest is placed in each pen which is stocked with a selected pair of brood fish. The female should be slightly smaller than the male, as the male guards the nest after spawning and fighting between the parents often occurs during this period. If larger, the female may chase the male away or even kill it, with the result that the eggs would not receive parental care and might even be eaten by the female. After introduction of the brood fish, the pen is checked on at least alternate days. If spawning has occurred, the female is removed from the

pen and returned to the brood pond. Either the male fish is left to hatch the eggs or the egg mass is collected and hatched indoors. If hatched in the pen, the fry swim out of the nest through the wire mesh into the pond. If the eggs are removed for hatching, each pen is stocked with a second female or a new male and female pair after removing the male that has spawned once.

The aquarium method of spawning is used only when a small number of fish are to be spawned at a time and greater control of spawning is required. Aquaria of 100–220l capacity with a constant flow of water are used.

Fish can be spawned at any season of the year, one pair at a time, by injecting the female with pituitary extract or HCG. The dose required is about 13mg pituitary extract per kg body weight, or an average of 1760mg/kg of HCG. If spawning does not occur within 24 hours, a subsequent injection may be needed. If the fish does not respond to three injections, it is replaced with another female. In the aquarium method, the eggs are hatched artificially.

If the eggs hatch in the spawning pond itself, or in the pen, the fry are collected (after driving off the male or removing it as appropriate) into suitable containers and transferred to fry ponds for rearing. Artificial hatching techniques are preferable, especially in pen spawning, as the spawning nests can be reutilized quickly andthe culturist will know more accurately the number of eggs hatched. It reduces losses to predacious insects and other fish, including the parent females.Though channel catfish eggs can be incubated in hatchery jars, troughs are more commonly used in commercial farms.

Hatching troughs are usually made of sheets of aluminium or stainless steel; their dimensions vary, but they are segmented by partitions across the middle, each segment having a drain and an inlet pipe. The segments make it possible to separate eggs in different stages of development. The eggs are kept in 7.5cm deep baskets, made of 0.6cm meshed hardware cloth and suspended by wire from the side of the trough, so that the water line is below the top of the basket. Paddles attached to a revolving shaft cause the movement of water on the eggs, in a manner similar to that made by male fish when they guard the nests in ponds.

Six to ten days are required for catfish eggs to hatch at temperatures in the range 21–24°C. To combat the growth of fungi, troughs are flush-treated once or twice each day with malachite green at the rate of 2ppm in the water.

The treatment is stopped 24 hours prior to hatching, as the chemical is highly toxic to fry. As the eggs hatch, the fry swim out of the baskets through the hardware cloth into the trough.

Fry can be reared in troughs or ponds, but trough rearing is preferred since it allows greater control and the fry are less exposed to predators. Rearing troughs are generally 2.5–3.7m long, 30–38cm wide and 25–38cm deep, made of wood, metal, plastic or fibreglass. A water flow of about 0.06–0.3l/min and a temperature range between 24 and 29.5°C are maintained. Fry reared in troughs have to be given complete feeds after the yolk sac is absorbed, which takes about eight days after hatching. Floating and non-floating types of commercial feeds, containing 28–32 per cent protein and other nutrients, are fed five or six times each day at the rate of 4–5 per cent of the fry weight. Many culturists feed fry initially with fine particle trout starter rations, that contain about 50 per cent protein. The protein percentage is reduced and the pellet size increased as the fry grow. In a few weeks, a typical catfish ration containing about 30 per cent protein is given. Fry can be raised to fingerling stage in troughs or moved to rearing ponds after they have grown to 2–4cm.

Fingerling ponds are frequently about half a hectare in size, and when stocked at the rate of 90000–125000/ha, fingerlings of 15–20cm can be produced in about four months. Predatory aquatic insects can be controlled with a layer of oil on the pond surface to prevent the insects from breathing atmospheric air. Fry reared in ponds may not need complete feeds as do those in troughs, but it will be safer to use them as the quantity of natural food in the pond is not always predictable. The ration of artificial feed is gradually increased from about 0.5kg per 0.8ha pond to about 4–5 per cent of the fry body weight. Starter feeds in meal or ground mash form may be changed to small pellets when the fish reach about 2.5cm in length. Many farmers produce only fingerlings, for sale to those who grow them to market size or stock recreational waters. There is greater demand for larger fingerlings of 15–20cm, rather than smaller 5–10cm ones. Raising of fingerlings of this size covers the first growing season.

Grow-out

Grow-out of channel catfish to market size takes a little less than two years after hatching, or one year from the fingerling stage. The usual market size is 500g to 1.4kg, though many are harvested at 450 to 600g size. Fingerlings aregenerally stocked in grow-out facilities in the spring, and harvested in about seven months in October or November.

The most common grow-out facilities are pond farms and they generally seem to be more cost-effective than other systems.The ponds are prepared for stocking by eradication of weed fish by application of rotenone. New ponds are fertilized with 16–20–4 or 16–2–0 NPK fertilizer at the rate of 56kg/ha. The stocking density depends mainly on the quantity and quality of the water supply and the desired size of the market fish. In ponds with a dependable water supply, a stocking density of about 3700–4900/ha is common. At the lower range of this density, the fish would weigh 500–600g at the end of the growing season. To obtain a fish of about 1.2kg weight, a third year of growth is needed. A stocking density of 2000–2500/ha is recommended for this purpose. Producers very often thin out the stocks from their stocking ponds after the second year of growth and maintain the lower density required for a third year of growth.

The use of commercially produced formulated feeds is a common practice in the catfish culture in the USA. In ponds where the fish have access to natural food, a feed containing 25 per cent protein may be enough, whereas in others a complete feed containing 30 per cent protein is required. Commercial catfish diets are made in different forms, the most common one being the extruded or hard pellet. Other forms used are dry meals and crumbles for feeding fry, floating pellets, semi-moist pellets containing 25–30 per cent water, and agglomerates prepared by rolling finely ground dry formulated feed into balls for fingerling and adult feeding.

The most common methods of feeding are hand feeding and self or demand feeding. Many farmers prefer the former practice, mainly because they can regulate the feeding more easily and closely observe the feeding activity. Self or demand feeders permit the fish to obtain feed when they want and reduce over-feeding, which appears to be a common problem in channel catfish culture. Blow feeders, or low-flying aeroplanes that dispense feed, are made use of in extensive farms. Feed conversion in commercial grow-out facilities during the second year of growth is generally 2kg feed for

1kg fish, although better conversion has been achieved with improved feeding and management. An average production in commercial pond farms is around 1500kg/ha, although production of up to 3000kg/ha has been reported.

Raceways with an adequate flow of water that allows an exchange twice every hour in each segment can produce much greater quantities of fish than ponds. The stocking density depends on the size to which the fish are to be grown. The usual rate is about 2000 fingerlings per 120m3 raceway, where with proper feeding and exchange of water about 1 ton of fish can be produced in 180–210 days. In raceways with a lower water flow, only lower densities of fish can be raised. For example, with a flow of 9.5l/s, only 3500–5000 fingerlings can be stocked. Stocking is carried out in spring and early summer, with advanced fingerlings of 15–20cm size. A complete feed, nutritionally richer than the feed used in ponds, is provided in raceways. The rate of feeding is usually 4–5 per cent of body weight twice a day, for two months after stocking, after which it is gradually reduced to about 3 per cent.

Tank culture of catfish, though only introduced comparatively recently, is reported to give very satisfactory results. Farmers who have adopted this technique report that a circular tank of 6m diameter and 0.6m depth gives the same production as a 0.4ha pond. High rates of stocking are possible if the tanks are provided with aerators. Complete feeds at the daily rate of 3 per cent of the body weight are fed twice a day. Protection from bright light appears to give better growth rates and so the tanks are either covered or housed indoors.

Cage culture of catfish is of greater value when the cages are installed in open waters rather than in ponds. The stocking rate is about 65 fingerlings per m3. Complete floating feeds are usually given at the rate of 3.5 per cent of body weight per day. This is gradually reduced to 2 per cent, depending on the quantity consumed.

Diseases

The major diseases that afflict channel catfish have been described. The only virus disease diagnosed is the channel catfish virus disease (CCVD), which may cause large losses of fingerlings in a short time. Like mostviral diseases, the only known means of eliminating CCVD is by the destruction of all brood stock associated with the epizootic. Haemorrhagic septicaemia and columnaris disease are important bacterial diseases of catfish that cause considerable mortality. A variety of protozoan diseases also infect the species, of which ichthyophthiriasis or ‘ich’ is the most important. Eradication of the parasite is possible only during its free-swimming stages and repeated treatments over a period of days or weeks are needed to eradicate all. Costiasis is another common protozoan infection, which causes high levels of mortality, especially among fingerlings.

Various species of the external parasite Tri-chodina affect channel catfish. They occur onthe body, fins and gills. Trichodiniasis is characterized by the appearance of irregular white blotches on the head and dorsal surface of infected fish. There may also be fraying of the fins and loss of appetite. Epidermal necrosis and excessive production of mucus may occur. Dips in 30ppt salt water, a 1:500 solution of acetic acid or a 1:4000 solution of formalin form the usual treatment.

Myxosporidian parasites of the genus Henneguya, monogenetic trematode Gyrodactylus and the copepod parasites Ergasilus, Argulus and Lernaea can cause mortality among catfish.

Harvesting and marketing

Seining and draining are the two main methods of harvesting catfish from pond farms. Draining is an effective method as it allows better management of pond soils, but in areas where refilling the ponds requires pumping it involves an additional major cost. Also, there appear to be some practical difficulties in synchronizing the completion of draining with the delivery time of the fish to live haulers. Seining has an advantage in this respect and it also permits partial harvesting. If the mechanized seining equipment described is used, labour requirements can be reduced. However, larger investments for equipment are required and complete harvesting will not be possible. In recreational waters, channel catfish are caught by hook and line, using an ordinary fish hook on a pole, trotline or spinning rod.

After harvest, the fish may have to be held for several days before marketing. Vats, tanksor small ponds are used for holding. The fish have to be fed at maintenance levels if the holding period is longer than a day or two. If large harvests are involved, some culturists use ‘live cars’ (rectangular enclosures of netting buoyed by a series of floats) into which the catch from a seine can be transferred through a framed opening. The live car itself can be opened or closed by means of a drawstring. The problem of off-flavours developed by catfish in ponds and methods of eliminating them have been referred.

Catfish are usually hauled in tanks made of wood, fibreglass or aluminium. About 1kg fish can be hauled in every 5l water, with a change of water every 24 hours. Devices for aeration are installed in the tank. In most cases, agitators that stir the surface water suffice. Deep tanks may, however, need aeration from the bottom.

Catfish are marketed as whole fish, dressed fish or steaks and fillets. The dressed or pan-dressed fish is the most popular product, with the viscera, skin, head and some of the fins removed. Fish of 500–650g are well suited for this type of product. For steaks, larger fish of about 900g or more are used. Fillets are made from small or large fish. Usually such processing and packaging is done in either farmer-operated facilities or in large processing plants.

The product is packaged for quick-freezing or for marketing fresh, wrapped in polyethyl-ene film or bags. Frozen fish are stored at -1 to 1.7°C before sale.

Economics

As in all types of aquaculture, the economics of catfish culture show considerable variations between farms, depending on the locationand culture system employed. Available data indicate that under prevailing conditions, pond farming is probably the most profitable system, although production up to fingerling stage only may sometimes give a better profit. Larger farms are more profitable than smaller ones. Production has to be at least 1500–2200kg/ha to make a reasonable profit. The benefits of double-cropping with trout have been discussed on trout farming. Some farmers rotate rice, catfish and soybeans to yield better returns. The agronomic crops benefit by the improved nutrient level of the soil, caused by the accumulation of excrement and unconsumed feeds during fish culture.

Related Topics