Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : Breast

Breast : Surgical Pathology Dissection

Breast

General Comments

A wide

variety of surgical techniques are em-ployed to biopsy or resect breast tissue.

In gen-eral, these specimens can be divided into several groups: (1) needle

core biopsies performed by radiologists; (2) small biopsies performed for

mammographic abnormalities; (3) “lumpecto-mies” for grossly benign palpable

tumors and grossly malignant palpable tumors; (4) mastecto-mies with or without

a lymph node dissection, performed for carcinoma; and (5) reduction

mammoplasties.

The

processing of these specimens can be difficult and labor-intensive for a number

of rea-sons. Breast specimens are fatty tissues that re-quire meticulous

attention to proper fixation to ensure adequate microscopic and

immunohis-tochemical evaluation. Breast specimens often harbor subtle

mammographic abnormalities that may not be apparent on gross examination.

De-tection of these lesions relies on careful dissection coupled with ample

tissue sectioning. Breast specimens usually do not contain useful anatomic

landmarks, yet important treatment decisions ul-timately rest on your ability

to assess the status of the specimen margins accurately. Detailed at-tention to

specimen orientation and margin des-ignation is therefore critical.

Examination of the Specimen

All

breast tissue, even if removed for cosmetic reasons, should be examined fresh.

It is much easier to appreciate subtle scirrhous areas that could correspond to

small invasive carcinomas in the background of fresh tissue. After formalin

fixation, all of the tissue is firm, making this dis-tinction more difficult.

Inking

Breast

specimens (with the exception of needle core biopsies) should be inked prior to

immersion in formalin. Before the ink is applied, blot the surface of the

specimen dry so the ink better ad-heres to the surface of the specimen. After

the ink is applied, again blot the surface of the speci-men dry. This step

helps prevent the ink from penetrating the tissues as the specimen is

sec-tioned. Immersion for 20 seconds in Bouin’s fixa-tive immediately after

inking may help fix the ink to the specimen, but remember to rinse the Bouin’s

solution from the specimen before sectioning. Always be certain that the ink is

completely dry before cutting into the specimen. Be patient; you may have to

wait 5 to 10 minutes or so for the ink to dry completely.

Sometimes

the surgeon designates (e.g., using sutures) the anatomic orientation of a

specimen. The easiest way to maintain this orientation is to use inks of

different colors to designate each of the six specimen margins (superior,

inferior, medial, lateral, anterior, posterior). If only one color is used, you

must keep track of and dic-tate which inked surfaces are represented in each of

the cassettes. Also, if the specimen is not sub-mitted in its entirety, it must

be stored so one can go “back to the bucket” and take more sec-tions from a

specific area as needed.

Fixation

Breast

tissue that has not been properly fixed compromises the ability of the

histopathology laboratory to cut high quality sections for mi-croscopic

examination, limits the ability of the pathologist to interpret difficult

“borderline” lesions (e.g., atypical duct hyperplasia), and di-minishes the

reliability of immunohistochemical assays (e.g., Ki-67 proliferation index,

estrogen and progesterone receptors) for predicting tumor behavior. If the

specimen is to be fixed prior to complete processing and sampling, take the

time to “bread-loaf” the specimen at 1-cm intervals before submerging it in

formalin. This step allows the formalin to penetrate all of the tissue.

Needle Core Biopsy

Record

the number, size, and color of the tissue cores. All of the cores should be

entirely submitted to the histopathology laboratory for further processing.

Each tissue block should be sectioned at three levels.

As part of the microscopic evaluation of these specimens, the histopathologic findings must be correlated with the clinical and mammographic findings. For example, if the biopsy specimen is from a mass lesion, your report should indicate whether the microscopic findings account for a breast mass. If, on the other hand, the biopsy was performed because of worrisome calcifications, your report should document the presence of these calcifications when they are found. Discrepancies between the microscopic findings and the clinical/mammographic findings may necessitate additional work on your part. If you cannot find calcifications when they were seen by mammography, additional levels of the tissue block should be cut. It may be necessary to confirm the presence of calcifications essary to confirm the presence of calcifications by obtaining radiographs of the paraffin blocks.

However, you should be aware that calcifica-tions that were

present in the tissue submitted to pathology (as documented in radiology by

speci-men radiographs) sometimes chip out of the block when it is sectioned by

the histotechnolo-gist. The presence of tissue tears in the hematoxy-lin and

eosin (H&E) section is a good clue that this has occurred.

Biopsies for Mammographic Abnormalities

Nonpalpable

lesions detected mammographically are often biopsied by the surgeon and the

specimen then sent to radiology, where a specimen radiograph is obtained to

confirm that the surgeon has indeed biopsied or excised the lesion detected on

the clinical mammogram. In these cases the radiologist frequently marks the

lesion with a needle or dye, and both the biopsy and the specimen mammogram are

then sent to the surgical pathology laboratory.

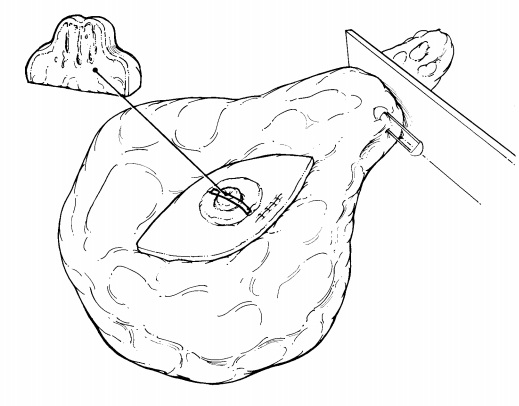

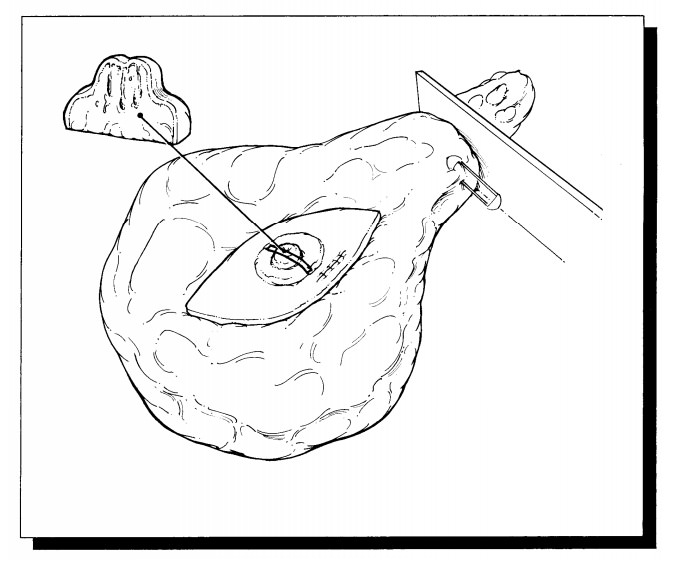

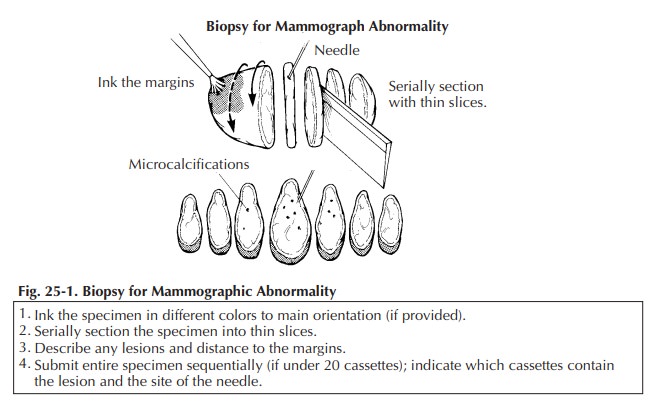

Once

received in pathology, the specimen should be measured, inked, and serially

sectioned (Figure 25-1). Take care to slice the breast thinly (2 mm). Take

advantage of the specimen radiograph; the gross findings can be correlated with

the lesion seen radiographically. If a lesion is seen, note the largest

dimension of the lesion and carefully note the relationship of the lesion to

the inked margins as well as the circumscription and nature of the border of

the lesion.

Sequentially

submit the entire specimen, up to 20 blocks of tissue, for histologic

examination. Sequential sectioning allows one to better reconstruct the

distribution of the lesion from the slides. When taking these sections, be sure

that the sections demonstrate the relation of the lesion to the closest inked

margin. Be sure also to designate which block contains the area marked by the

radiologist’s needle as containing calcification.

For large biopsy specimens that cannot be completely submitted in 20 or fewer sections, the extent of tissue sampling is not clear. Owings et al. suggested a method for selective tissue sampling in these large specimens. According to their method, initial sampling should include the submission of all tissue corresponding to radiographic calcifications and all surrounding fibrous tissue.

If carcinoma or atypical

duct hyperplasia is identified in these initial sections, the remaining tissue

should be submitted in its entirety to determine the extent of the lesion and

the status of the margins and to exclude inva-sion in cases of ductal carcinoma

in situ.

Lumpectomy

Lumpectomy for a Grossly Benign Palpable Mass

A

lumpectomy specimen from a palpable mass that is grossly benign should be

measured, inked, and serially sectioned perpendicular to the clos-est palpable

margin. Inspect the cut surface and record the size and appearance of the

lesion as well as its distance from the margins. Sequen-tially submit the

entire lumpectomy specimen in up to 10 cassettes. Be sure that your sections

show the border of the lesion with the surrounding breast tissue (important for

distinguishing fibro-adenoma from phyllodes tumors), and take perpendicular

sections from the lesion to the margins. If the margins are designated, be sure

to obtain a section perpendicular to each of the six margins. Cost-effective

strategies for handling large lumpectomy specimens have also been proposed.

Schnitt et al.11,12 suggested submit-ting a maximum of 10 initial

sections of the fibrous tissue in these cases, as carcinoma and atypical

hyperplasia are unlikely to be found in the fatty tissue alone.

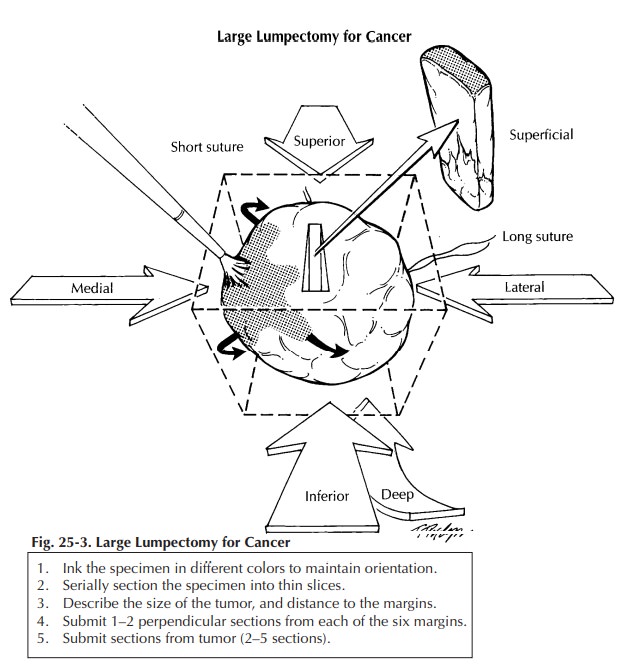

Lumpectomy for Grossly Identifiable Cancers

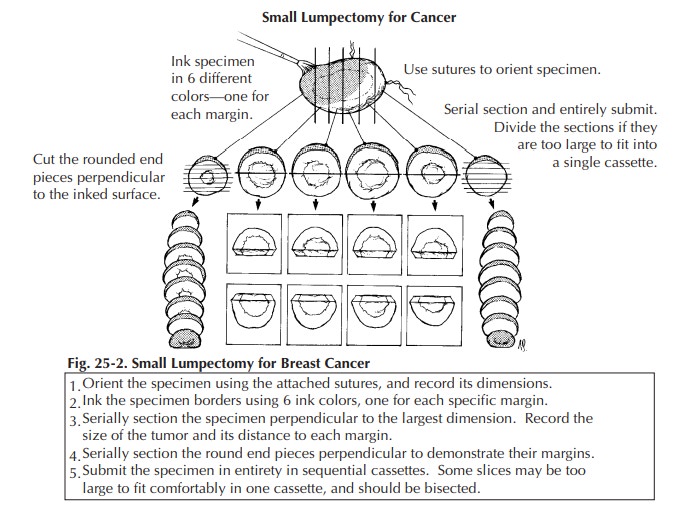

Lumpectomy

biopsies for grossly identifiable cancers are usually brought to the surgical

pathology laboratory with some indication of orientation provided by the

surgeon. Frequently, but not universally, a short stitch is used to desig-nate

the superior aspect of the specimen and a long stitch to designate the lateral

aspect of the specimen. From these two landmarks you can then determine the

inferior, medial, anterior, and posterior margins. As illustrated, these

margins are easier to conceptualize if you think of the specimen as a cube.

After orienting the speci-men, measure it, ink it, and obtain one or two

perpendicular sections from each of the six mar-gins (superior, inferior,

medial, lateral, superfi-cial, deep). Serially section the specimen at 2- to

3-mm intervals. Note the size of the tumor and the distance to each of the

margins. Obtain two to five sections of the tumor. If a portion of skin is

present, it should also be sampled for histologic examination. If the

lumpectomy specimen is rela-tively small, submit it entirely (Figure 25-2). For

large lumpectomy specimens, where the entire specimen cannot be submitted in 20

cassettes, submit representative sections (Figure 25-3).![]()

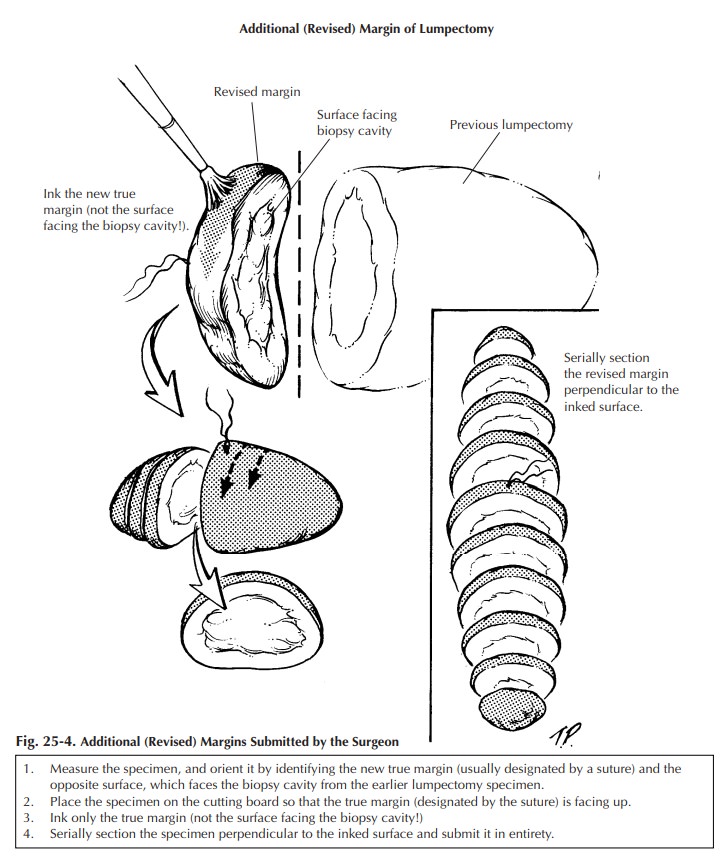

Additional (Revised) Margins Submitted by the

Surgeon

Sometimes

the surgeon separately submits addi-tional (revised) margins for one or all six

of the lumpectomy surfaces. Usually these specimens appear as a strip of tissue

with a stitch on one face marking the new margin. The opposite sur-face, which

would face the lumpectomy speci-men, often contains fresh blood and is not a

true margin. Ink the surface containing the stitch, obtain serial sections

perpendicular to the ink, and submit all of the sections for microscopic

examination (Figure 25-4). Do not ink the oppo-site surface; otherwise, it may

be impossible to tell which is the true margin.

Re-excision Lumpectomy

Re-excision

lumpectomies are generally per-formed because a positive margin was identified

during a prior excision. Therefore, specimen sam-pling should focus on the

biopsy cavity to docu-ment the presence of residual disease and on the new

specimen margins to ensure the adequacy of tumor removal during the

re-excision. Try to submit re-excision specimens in their entirety if they can

be submitted in fewer than 10 cassettes. If the biopsy cavity appears grossly

benign, two sections per centimeter of greatest specimen diameter is probably

adequate.

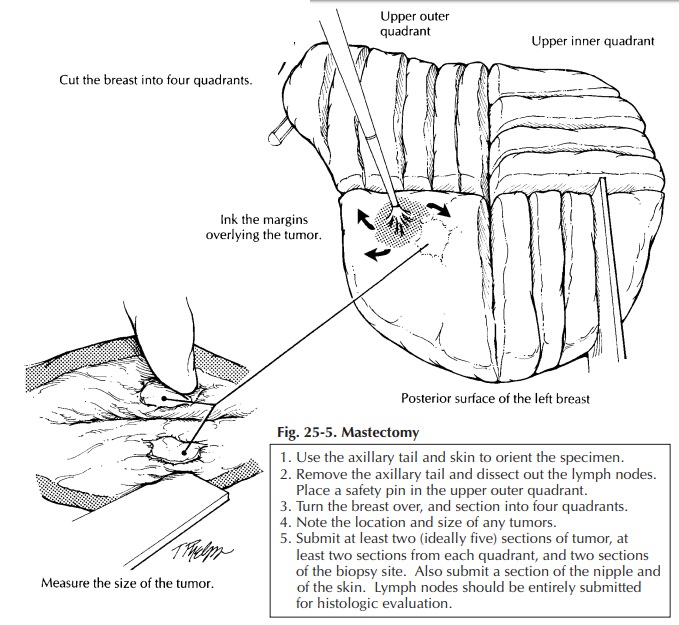

Mastectomy

True radical mastectomies are seldom performed anymore. The procedure includes complete axillary dissection including removal of the modified radical mastectomy is more common.

With this procedure the undersurface of the

spec-imen is composed only of fascial planes with occasional shreds of

pectoralis major muscles attached. The anterior surface usually contains an

island of skin and nipple with the subcutaneous tissue extending beyond it.

Nevertheless, com-plete axillary dissection typically is included within the

specimen, forming an elongated tail at one end of the otherwise elliptical

specimen. Most mastectomies are performed after a core needle biopsy has

established a diagnosis of in-vasive carcinoma or after a lumpectomy has not

been successful in completely removing an in

situ and/or invasive carcinoma.

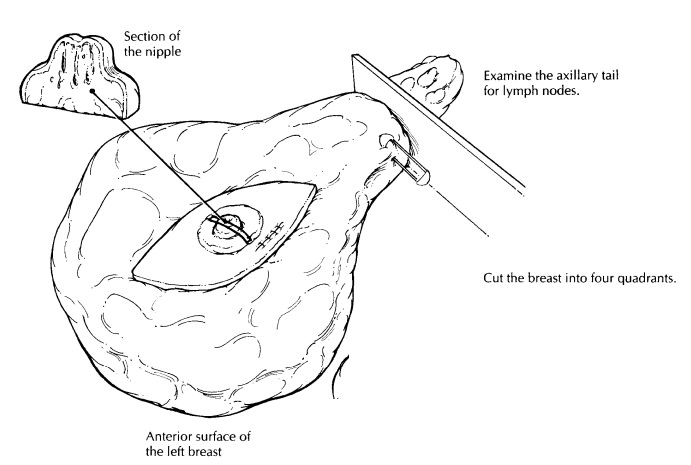

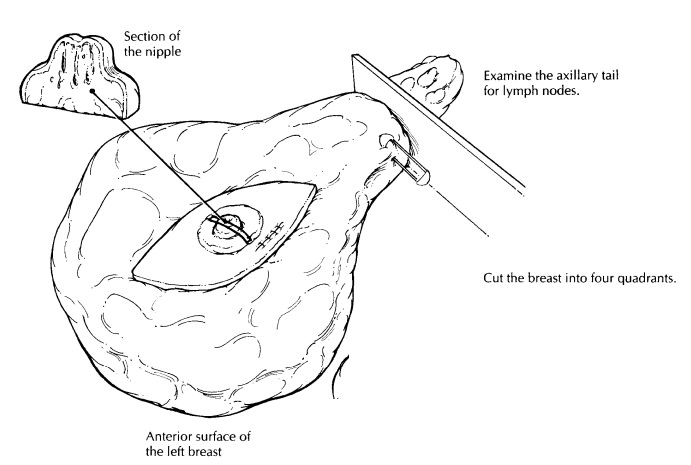

First,

orient the specimen to localize the four quadrants of the breast correctly.

This step should not be difficult if you use the axillary contents, the

sidedness of the breast, and the surgeon’s description of the location of the

tumor. Once the specimen has been oriented, place a safety pin in the corner of

the upper outer quadrant. This practice helps you to reorient the specimen

quickly in case you have to return to the speci-men. Weigh and measure the

specimen; then de-scribe the skin, nipple, and any biopsy sites seen. The

axillary tail can be removed now for later examination. Next, take the time to

palpate the specimen. Localize the biopsy scar, the biopsy cavity, and any

masses. Examine the deep surface of the specimen for attached fragments of

skeletal muscle, and ink it so perpendicular sections can be obtained to

evaluate the deep soft tissue margin. Also ink the exposed breast tissue

lateral to the skin ellipse on the anterior surface of the specimen (preferably

with ink of a different color). These constitute the anterior margins. Hence,

all surfaces except for the skin and axillary tail should be inked.

The

breast can then be placed skin surface down on a cutting board and sectioned.

As illus-trated (Figure 25-5), use the nipple to center the specimen; then with

two long perpendicular cuts section the breast into four quadrants. Each

quad-rant can be further sectioned, each in its own direction. These cuts

should not go all the way through the specimen but, instead, should leave the

pieces attached together by a rim of unsec-tioned breast or skin. This

procedure not only helps orient the specimen in a clinically relevant way, it

helps remind you to document in which quadrant(s) the lesion lies The gross

dictation should include

(1) the

over-all dimensions and the weight of the specimen;

![]() the

overall dimensions of the skin surface;

the

overall dimensions of the skin surface;

(2)

the presence or absence of a biopsy scar and

biopsy cavity and their relation to the nipple;

(3)

the presence of any retraction or ulceration of

the nipple and/or surrounding skin; (5) the pres-ence or absence of muscle on

the undersurface of the specimen; (6) the

size and gross appearance ofthe tumor including the quadrant of the breast in

which it is localized; and (7) the distance of thetumor to the deep and

anterior margins. At least two and ideally five sections of the primary lesion

should be submitted for histologic examination. Two sections can then be

submitted from each of the remaining breast quadrants. If the mastec-tomy was

performed as a prophylactic procedure in a patient with an in situ carcinoma, submit at least three sections from each

quadrant; also submit any suspicious lesions in their entirety. Submit a

section of the nipple and one of the skin in the area of the prior biopsy site.

Finally,

dissect all lymph nodes from the axillary contents. If lymph nodes are

separated into levels I, II, and III by their relationship to the pectoralis

minor muscle (lateral, below, and medial to it, respectively), maintain this

orienta-tion. When dealing with axillary lymph nodes in patients with carcinoma

of the breast, it is particularly important to identify and evaluate each lymph

node and to submit lymph nodes that are grossly negative for tumor in their

entirety. Grossly positive nodes do not need to be submitted in their entirety.

The size of the tumor in the grossly involved lymph node should be documented

in your gross report.

Reduction Mammoplasty

There

are no rigid criteria that dictate the num-ber of sections to submit from

reduction mam-moplasty. In the absence of such criteria, a few considerations

provide some helpful guidelines for specimen sampling. First, thorough gross

examination of the thinly sliced specimen is the key to identifying clinically

significant lesions. Second, because the risk of breast cancer in-creases with

age, submit relatively more sections from specimens removed from older

patients.

We

suggest submitting three sections from patients under 30 years of age and five

sections from patients over 50 years of age. Third, because carcinomas and

atypical hyperplasias are much more likely to involve fibrous breast tissue

than fatty breast tissue, sections should selectively target dense and fibrotic

breast parenchyma. The identification of atypical lesions or carcinoma on these

initial sections indicates the need to go back to the specimen to obtain

additional sections.

Important Issues to Address in Your Microscopic Surgical Pathology Report

·

What procedure was performed and what

structures/organs are present?

·

What are the gross size and location (nipple,

central portion, upper inner quadrant, upper outer quadrant, lower inner

quadrant, lower outer quadrant, axillary tail) of any tumors identified? What

is the microscopic size of the tumor? Are these measurements concor-dant?

·

Are the tumors in situ or infiltrating? If the lesion contains both in situ and infiltrating carcinoma, what

proportion of the lesion is in situ,

and what proportion is infiltrating?Does in

situ carcinoma extend away from the main tumor mass?

·What are the histologic type

and grade of the in situ or

infiltrating carcinoma?

·

Is vascular/lymphatic invasion present?

·

Is there skin or nipple involvement?

· Does the

tumor involve the margins of resec-tion? If it is close to a margin (i.e., less

than 10 mm), record in millimeters the exact dis-tance of the tumor from each

of the margins.

· Does the

tumor directly extend into the chest wall or the skin?

· Are

microcalcifications present?

·

Record the location and number of nodes

ex-amined and the presence or absence of meta-static carcinoma in these nodes.

What is the size of the largest metastasis? Does the metastasis extend beyond

the lymph node capsule into the surrounding perinodal fat?

Breast Implants

The

handling of prosthetic breast implants de-serves a special note. We suggest

that you follow The College of American Pathologists (CAP) rec-ommendations.13Briefly,

they suggest that you first weigh the implant and describe its external surface

(e.g., smooth, textured), its contents (clear gel, oil, watery fluid), and its

condition (intact or ruptured). Next, document any inscriptions printed on the

implant and photograph the implant,

particularly if it is ruptured. You can then turn your attention to the tissue

capsule—the wall of fibroconnective tissue that forms around the breast

implant. Weigh and measure the capsule, describe its inner surface, and submit

one or two tissue cassettes of the capsule for histologic examination. If any

nodules are present in the capsule, they should be sampled more exten-sively.

Finally, store the implants. With the current flood of litigation, the implants

should probably be stored indefinitely.

Related Topics