Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : Bone, Soft Tissue, and Skin

Skin : Surgical Pathology Dissection

Skin

General Comments

Skin

biopsies comprise a large component of the volume of many anatomic pathology

labo-ratories. These biopsies come in many shapes and sizes, both because of

the ease with which the cutaneous surface can be sampled and also because

biopsies are performed using a wide va-riety of techniques. Specimens are

generally ob-tained to diagnose tumors, to ensure complete excision of tumors,

and to identify or confirm the nature of cutaneous inflammatory diseases.

Understanding the suspected diagnosis and pur-pose of the procedure will help

expedite the pro-cessing of the tissue and ensure an accurate diagnosis.

Small Biopsies

Specimens

obtained to establish the diagnosis of a cutaneous tumor are usually performed

by the shave biopsy technique, punch biopsy tech-nique, or curettage.

Determining the adequacy of resection in fragmented curettage specimens is not

possible. In most other instances, determining resection margins is often not

requested, because a second procedure is anticipated by the physi-cian based on

the diagnosis. Nonetheless, some physicians may request an estimate of tumor

ex-tension to the resection margins, and in fact the occasional tumor is

completely removed by deep shave biopsy or by punch biopsy procedures.

Embedding the tissue in an orientation such that sections are taken in a plane

perpendicular to the epidermis allows easy identification of surg-ical margins

along the exposed dermis. Ink the exposed dermis before sectioning specimens

greater than 0.5 cm in largest dimension. In this manner, margins may be

reported as free or involved in the planes of section. Bisect any specimen 0.5

cm or greater in largest dimension and at least trisect any shave biopsy

specimen 1.0 cm or greater. Tissue bags or similar aids can help confine small

pieces of skin.

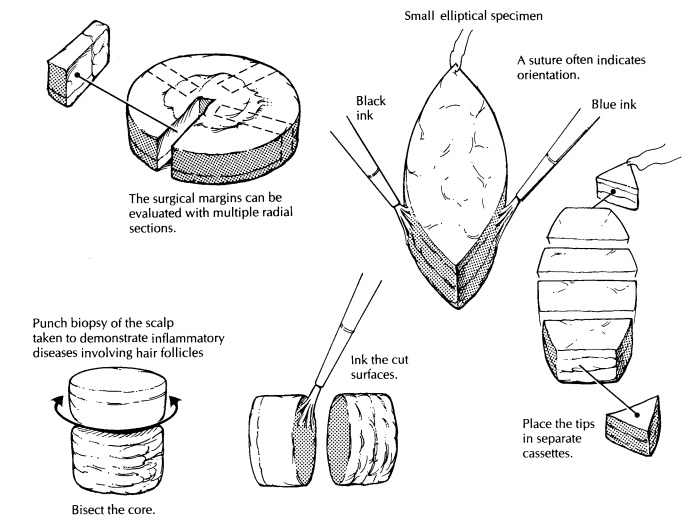

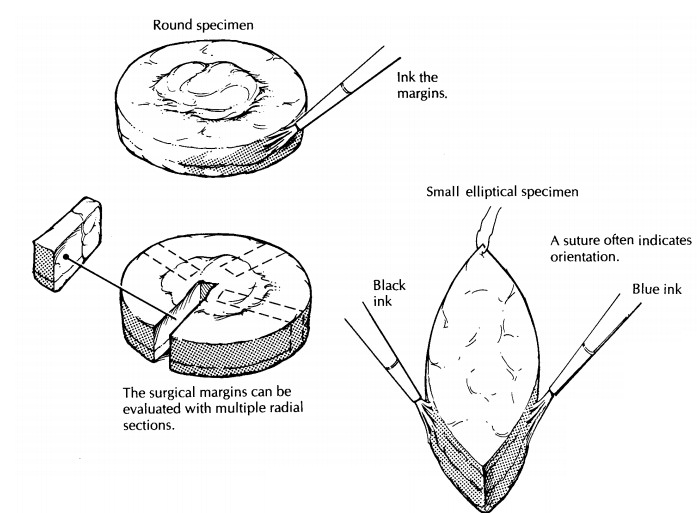

Elliptical Specimens

Many excisional specimens are submitted as el-liptical pieces of tissue because this shape leaves wounds that lie parallel to skin tension lines, allowing easy closure and good cosmesis. That said, excisional specimens can arrive in a variety of other shapes, especially from the face, based on the anticipated closure. Round, triangular, and rhomboid specimens should be expected. Usu-ally, there is some indication of how the specimen was oriented. For example, there can be a suture in one tip indicating the superior margin or ink placed on one or several surfaces of the tissue with an accompanying designation as to orienta-tion. Note such identifiers in your gross descrip-tion, and ink resection margins, including the deep margin. Use enough colors (generally the same ones used by the surgeon) to allow for accu-rate determination of precisely which margins are involved or free once the tissue is sectioned. In elliptical and rhomboid specimens, remove the small tips of the tissue fragments and place them in separate cassettes if specimen orientation is provided; one cassette may be used in the absence of anatomic identifiers. Embed the cut surface of the tip (i.e., not the surgical margin) in the block such that tissue sections progress toward the tip and become smaller over multiple tissue levels.

In this way, residual tumor may be traced out into the tip. The

body of the specimen can then be serially sectioned perpendicular to the

epi-dermis in sections of roughly a nickel’s width. Multiple tissue sections

may be placed in sin-gle cassettes, but when necessary single slices can be

placed in cassettes to allow for more accurate determination of the location of

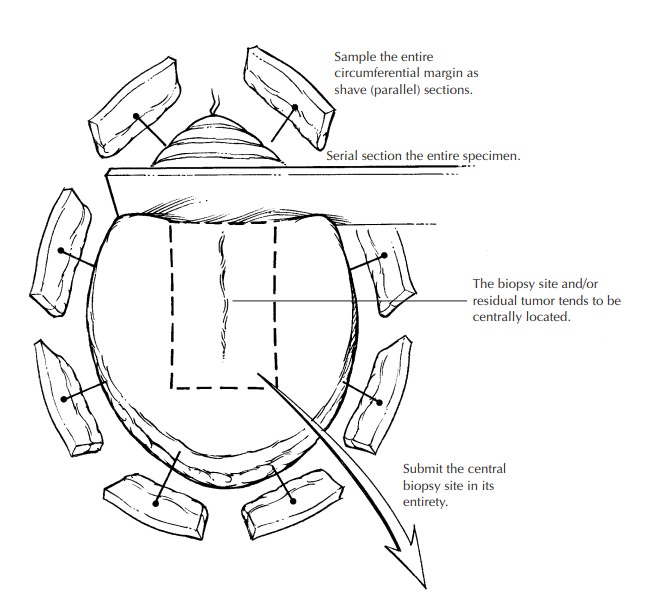

resection margins involved with tumor. Most specimens may be submitted entirely

in this fashion. Larger resec-tions for melanoma require sampling of the

mar-gins based on visual identification of where the tumor is (was) located. In

this instance, multi-ple samples taken perpendicular to the margin of resection

and including the tumor (or biopsy wound) are recommended. The deep

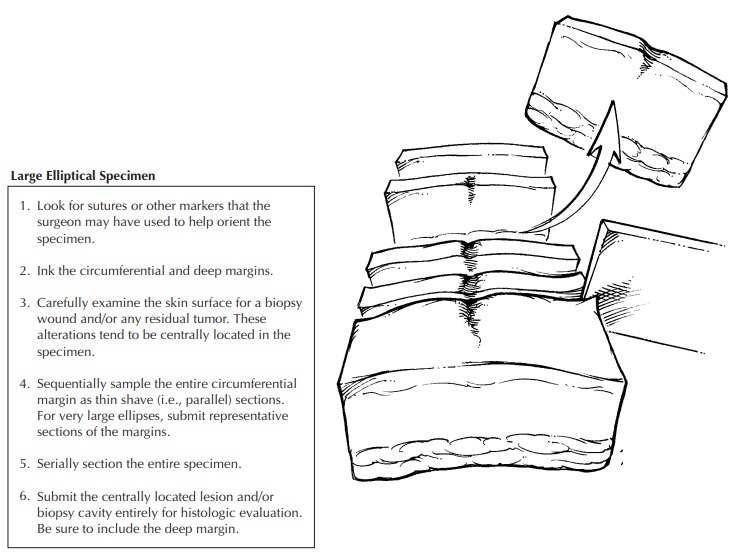

subcutane-ous margin may have to be sampled separately. Alternatively,

sequential sampling of the entire circumference of especially large elliptical

speci-mens may be undertaken as shown in the illustra-tion. The biopsy wound,

scar, or residual tumor is generally centrally located and should be sub-mitted

in its entirety. In this manner, all critical areas of the specimen are

examined, although some tissue is not processed.

Round Specimens

Small,

round excisional specimens, generally from the forehead, are a challenge. If

the surgeon places an identifier on the tissue, use this infor-mation to

localize the other resection margins. Because no tips are present to remove,

one ap-proach to these specimens is to tangentially shave a small piece of

tissue and embed these shaves as described previously for tips from ellip-tical

specimens, with subsequent serial slicing of the remaining tissue. The tips of

elliptical specimens are generally separated from the tumor by a reliable

amount of uninvolved skin. This safe zone is absent in round specimens where

tumor may be close to all margins. An alternative ap-proach is, therefore, to

obtain numerous sections in radial configuration, but visualization of all

margins is more difficult with this approach.

Irregularly Shaped Specimens

A

similar problem arises in determining ade-quacy of resection margins at the

base of riangular specimens. The base of such speci-mens generally abuts some

cosmetically sensi-tive structure such as the eyebrow or tragus. It is

difficult to determine if a margin is clear of tumor in sections taken parallel

to the base of the triangle if the tumor is near the resection margin. On the

other hand, perpendicular sections may miss a positive margin in the remaining

tissue sections. The most reliable approach is to pay scrupulous attention to

the gross appearance of the tumor and its relationship to the margins when

dissecting round and triangular excisional specimens from the skin.

Punch Biopsy

The most

popular method of skin sampling in the evaluation of inflammatory skin

conditions is the punch or trephine biopsy. A core of tissue is obtained in

this manner. Epidermis, dermis, and subcutis are usually easy to identify, and

the specimen should be embedded such that tissue sections are obtained

perpendicular to the plane of the epidermis. Punch biopsy specimens greater than

0.4 cm in diameter should generally be bisected. Read the clinical history carefully! If the clinician suspects an

infectious agent, requesting appropriate special stains at the time tissue is

submitted for histology will greatly shorten the time it takes to diagnose a

case. Dermatophyte in-fection is the most commonly overlooked clinical and

histologic diagnosis in the skin; obtaining fungal stains prospectively is

never a waste of time or money. Certain skin conditions display only subtle or

focal histologic findings, and serial sectioning of the block may be required

to iden-tify these processes, especially if a 6-mm punch bi-opsy specimen is

submitted from a 1- or 2-mm clinical lesion. Examples include folliculitis,

der-matitis herpetiformis, and transient acantholy-tic dermatosis.

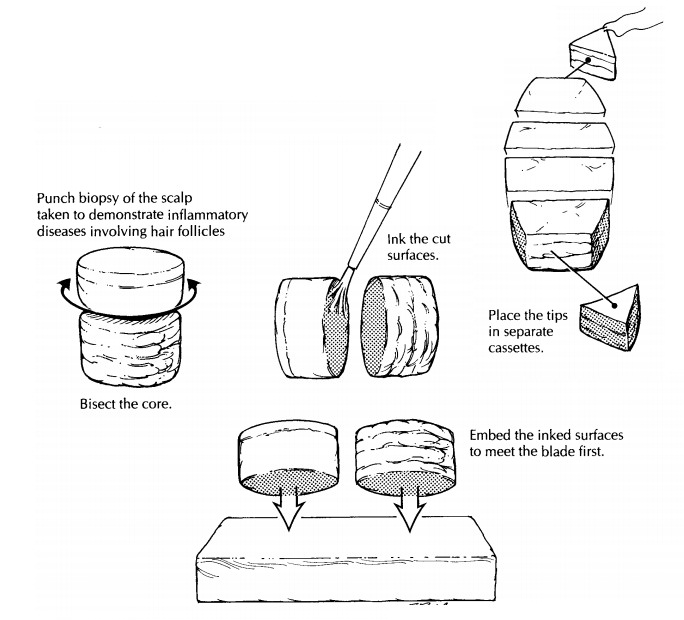

Punch Biopsies of the Scalp

Increasingly,

dermatopathologists prefer to inter-pret punch biopsy specimens from the scalp,

taken to diagnose inflammatory conditions, in sections parallel to the plane of

the epidermis. Perpendicular sectioning results in the identifi-cation of few

hair follicles in a given tissue section, and then the hair follicles are only

par-tially seen. Parallel sectioning is performed as follows. Bisect the core

of tissue in a plane hori-zontal to the epidermis at a level approximately 1 mm

above (i.e., toward the epidermis) the junc-tion of the dermis and subcutis.

Ink and embed the cut surfaces such that the inked surfaces face the microtome

blade. The tissue is serially sectioned with all tissue placed on slides. We

stain every other slide to reduce the overall number of slides examined as well

as to provide unstained slides for fungal stains if indicated after an initial

inspection of the tissue. This method allows all follicles at a given depth in

the skin to be exam-ined in one tissue section. Examination of serial sections

allows the complete assessment of folli-cles and follicular units contained in

the core of tissue. Determination of interface changes at the epidermis (e.g.,

for lupus erythematosus) is gen-erally still possible despite the horizontal

sec-tioning, but identification of epidermal atrophy is nearly impossible.

Embedded as described above, the series of slides provides sections from two

pieces of tissue with progression toward the epidermis in one piece and toward

the deep margin (hopefully subcutis) in the other.

Other Specimens

Dermatologic

surgeons may submit somewhat untraditional specimens. Liposuction specimens

consist of a variable volume of fat and sero-sanguineous fluid. While such

specimens may be submitted as a ‘‘gross only,’’ always examine a representative

amount of fat to reduce the chances of missing the unsuspected superficial

liposarcoma. Taking representative sections of certain common benign tumors

(e.g., lipomas, cysts, keloids) is acceptable.

Specimens from Moh’s Micrographic Surgery

A

complete description of Moh’s micrographic technique of histologically

controlled cutaneous surgery is beyond the scope of this topic. In brief, after

tumor debulking, wafer-thin planes of tissue are obtained from the wound bed in

an orientation horizontal to the epidermis. The sur-geon then carefully marks

the fresh tissue to establish resection margins and to identify the position in

the wound bed. A map of the tissue and markings is drawn. The tissue is divided

and mounted for frozen sections. The surgeon examines these sections while the

patient re-mains in the operating suite and the wound is still anesthetized.

Identification of tumor at a resection margin prompts removal of another plane

of tissue only in the involved area(s) and so on until complete removal of

tumor is en-sured. This technique offers a higher cure rate than conventional

procedures and is tissue spar-ing. Based on the surgeon’s routine, frozen

tissue sections are placed on the slide such that tissue nearest the resection

margin can be identified.![]()

Pathologists

can become involved in this proce-dure in three ways. First, the dermatologic

sur-geon may seek a second opinion regarding the presence or absence of tumor

in a particular frozen section. Second, a review of the frozen section slides

may be requested if there is a per-ceived discrepancy with the biopsy

diagnosis. Third, in rural areas, dermatologists will perform a similar

modified technique, so-called ‘‘slow Moh’s.’’ Here, planes of skin are

submitted as fixed tissue from a similarly prepared wound bed. The tissue must

be processed in horizontal sections, with an effort made to provide anatomic

localization of involved margins based on infor-mation provided by the

clinician. In the face of positive margins, the clinician will reanesthetize the

(now granulating) wound base and obtain another plane of tissue. Success in

this endeavor requires exceptionally good communication be-tween the clinician,

pathologist, and laboratory personnel. Occasionally, closure is delayed while

immunohistochemistry is performed on puta-tively negative margins to ensure

removal, par-ticularly for melanoma, using S-100 protein.

Important Issues to Address in Your Surgical Pathology Report on Melanomas

· What

procedure was performed, and what structures/organs are present? Specifically,

record the components present (e.g., skin, subcutaneous tissue, and other soft

tissue such as muscle or nerve).

· What is

the histologic type of the tumor?

· What is the growth phase?

· What is

the deepest level of penetration of the tumor (confined to the epidermis, into

the papillary dermis, filling the papillary dermis, into the reticular dermis,

into the subcutane-ous tissue)?

· What is

the maximum tumor thickness? (Mea-sure from the top of the granular layer to

the deepest extent of the tumor.)

· Are any margins involved by tumor?

· Is the

tumor ulcerated?

· How many

mitotic figures are identified per square millimeter?

· Are any

precursor lesions identified?

· Is any

evidence of regression of the lesion present?

· Is any

host inflammatory response to the tumor present?

· Is there

evidence of vascular or neural invasion?

Related Topics