Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : Bone, Soft Tissue, and Skin

Bone : Surgical Pathology Dissection

Bone

General Comments

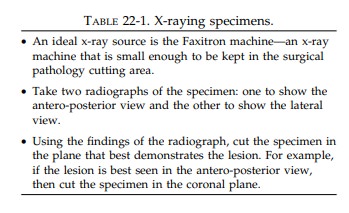

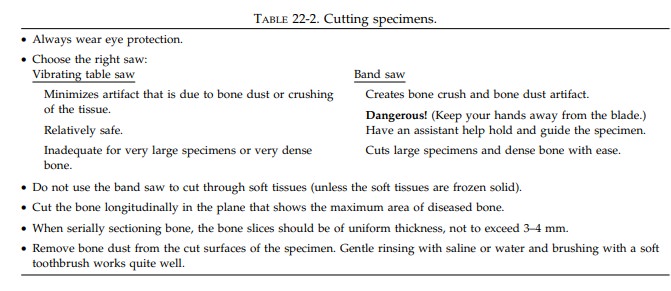

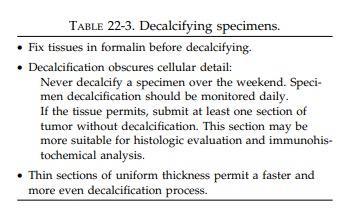

The hardness of bone introduces three challenges that are unique to the dissection of bone speci-mens: (1) Many lesions involving bone are not easily appreciated simply by palpating and inspecting the intact specimen. This inability to pinpoint the lesion may frustrate attempts to demonstrate its size and location when cutting the bone specimen. (2) Bone specimens cannot be easily dissected and sampled with standard knives and scalpels. (3) Since the microtome blade also cannot penetrate bone, bone cannot easily be sectioned in the histology laboratory. Fortu-nately, each of these obstacles can be overcome. Specimen radiographs (Table 22-1) allow one to visualize the extent and location of the patho-logic process so that the specimen can be cut in the proper plane; appropriate saws (Table 22-2) allow one to cut bone without destroying the speci-men; and finally, special solutions (Table 22-3) can demineralize bone making it easier to sec-tion for microscopic evaluation. Thus, the success-ful dissection of bone specimens requires that the prosector master the use of radiography, special techniques, instruments, and a variety of chemical solutions.

Small Bone Fragments

Whether

dealing with bone biopsies, currettings, or the removal of small bones, there

is always the danger of overdecalcifying the tissue. Efforts to minimize the

time in decalcification solution and to separate out tissue fragments that do

not require decalcification will reap great rewards when evaluating these

tissues microscopically. When it is necessary to cut a bone fragment before

processing, orient and cut the bone to show as much surface as possible. For

example, small tubular bones such as metatarsals or ribs should be cut

longitudinally rather than in cross section. When articular cartilage is

present, sections should be taken to show its relationship to cortical bone.

For specimens consisting of multiple pieces of tissue, soft tissues should be separated

from bone and processed routinely in formalin without decalcification, while

pieces of bone should be grouped in cassettes ac-cording to size and density to

allow for uniform decalcification.

Large Bone Specimens

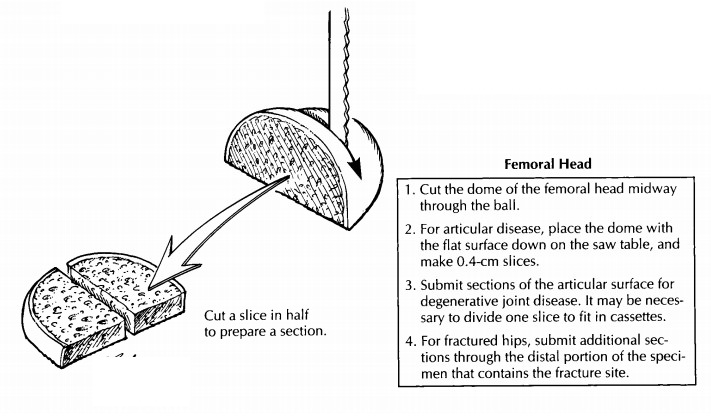

Femoral heads are the most common example of large bone specimens. They are usually removed because of either osteoarthritis or a hip fracture. Consequently, it is particularly important to identify, inspect, and sample the articular surface and any fracture site.

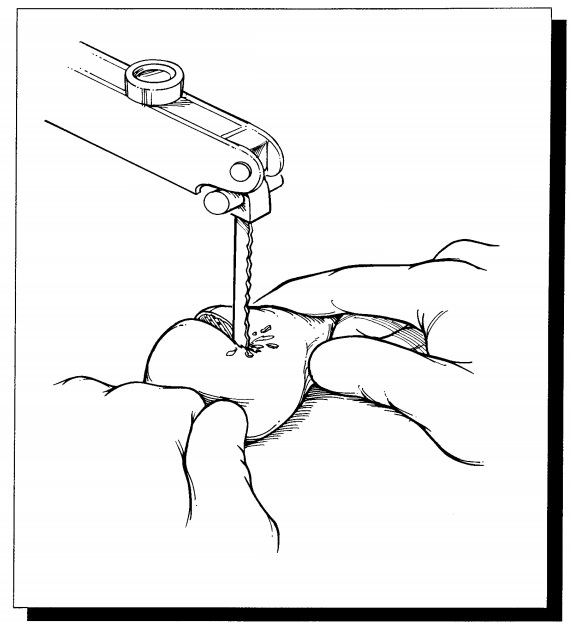

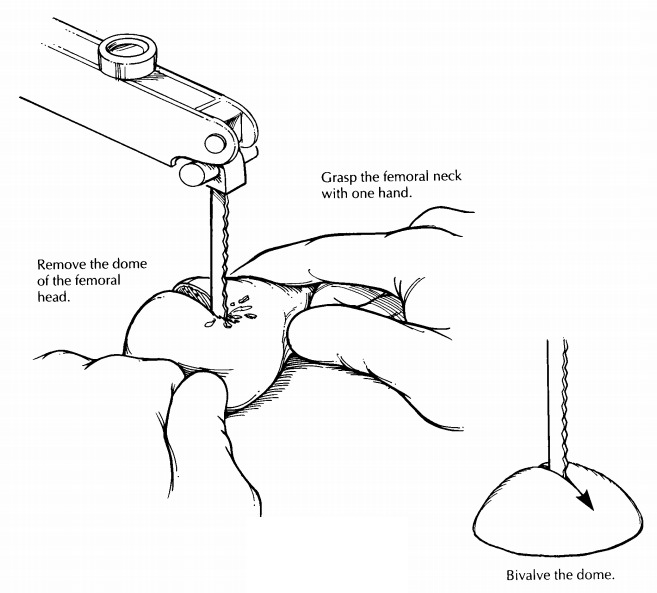

Measure the specimen and describe the articular cartilage,

noting whether it is eroded, frayed, pitted, or absent. The presence of

osteophytes should also be noted. As illus-trated, separate the dome of the

femoral head from the neck, then place the cut surface of the head on the table

saw, and section it into 4-mm slices in a plane perpendicular to the articular

cartilage. Note the density of the bone and the thickness of the cartilage. In

a similar manner, serially section the femoral neck. Look for the presence of

blood clot, marrow hemorrhage, or a neoplasm.

Sampling for histology should be guided by the clinical history and gross findings. For cases of osteoarthritis, sample the femoral head to show cartilage destruction and the reaction of the un-derlying bone. In cases of fracture, direct your attention to the fracture site; most of the sections should come from this area. Always submit at least one cassette of soft tissue including the syno-vial membrane and capsule.

Segmental Resections and Amputations for Neoplasms

Segmental Resections

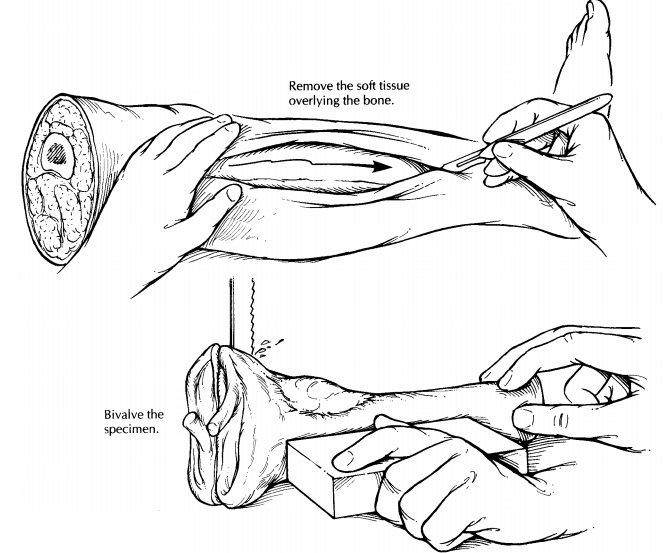

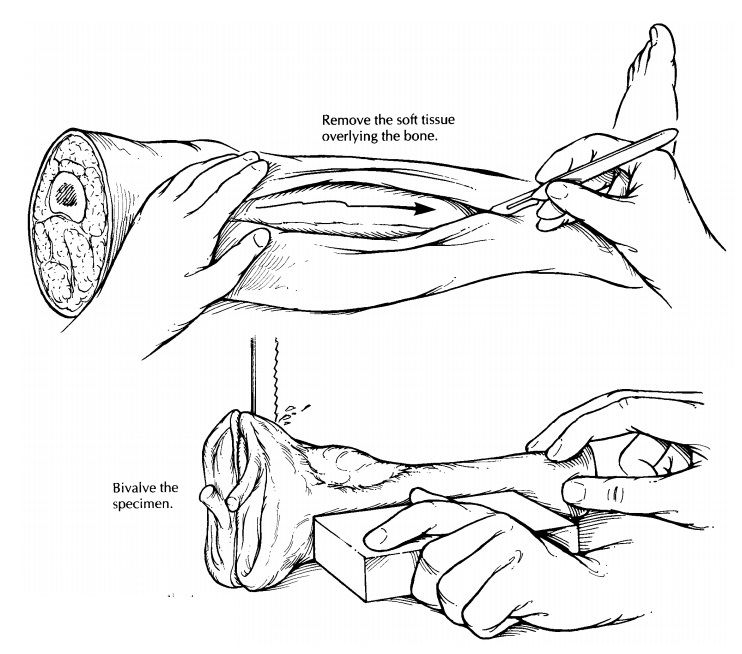

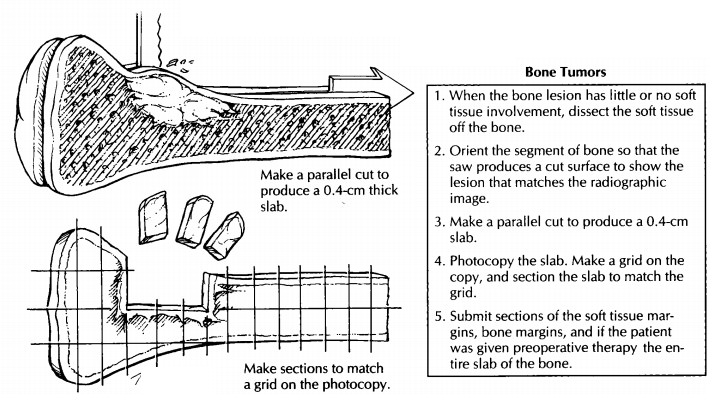

Segmental

resections of bone are performed for malignant neoplasms and aggressive benign

tumors. Because local recurrence is an important complication, the margins of

resection need to be carefully evaluated. The soft tissue margins are best

sampled while the specimen is intact and still easy to orient. After inking the

soft tissue resection margin, sample the margin using per-pendicular sections

from those areas for which there is gross or radiologic suspicion of margin

involvement.

After soft tissue margins are sampled, decide which plane of section will best demonstrate the lesion. The radiographic findings will help guide this strategy. For the saw to cleanly pass through the bone, expose the surfaces of the bone as illustrated by cutting through and peeling back the soft tissues in this plane. Next, bisect the bone in the appropriate plane (usually the coronal plane) using a band saw. Inspect the cut surface. The extent of the lesion should then be measured and described. In addition, the presence of corti-cal penetration and soft tissue extension should be noted. Look for noncontiguous ‘‘skip’’ lesions in the medullary canal, and measure the distance from the edges of the tumor to the bone resection margin. Scoop a small amount of marrow from the end(s) of the bone, and submit this marrow as the bone margin(s).

An

alternative method is to freeze the entire specimen. The frozen specimen does

not re-quire removal of the soft tissues before cutting the bone. Thus, the

relationship of the bone neo-plasm to soft tissue spread is better preserved.

Now you

are ready to cut a slab from the face of the bone cut surface. Place one half

of the bisected specimen on the band saw, and cut a complete 4-mm-thick slab,

then photograph and x-ray the slab. Ideally, this slab should be thin, uniform,

and represent the greatest surface area of the tumor. Before sectioning the

slab further, make a representation of the slab to map the precise location of

each section submitted for his-tology. One method is to photocopy the slab and

then to draw grids slightly smaller than your cassette size on the photocopy.

The entire slab can then be blocked out and submitted for micro-scopic

examination according to the grids on the photocopy.

When the

patient has received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the entire face of the slab

should be evaluated microscopically to determine the percentage of tumor

necrosis. When the patient has not received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, you may

be more selective in the sections that you submit for histology. Important

areas that should always be sampled include: (1) the intramedul-lary component

of the neoplasm; (2) penetration of the tumor through the cortex; (3) extension

of the tumor into soft tissues; (4) the interface of the tumor with normal

bone; (5) involvement by the tumor of an articular surface and/or joint space;

and (6) the bone margin(s).

Amputation Specimens

Although

amputations for tumor appear more complex than segmental resections as a result

of their size and bulk, they can be dissected along the same guidelines given

for segmental resections. Indeed, after margins are sampled, the portion of the

limb containing the bones and joints not involved by the neoplasm can be

removed. This, in essence, converts the specimen to one that is similar to the

segmental resection.

Important Issues to Address in Your Surgical Pathology Report on Bone Tumors

· What

procedure was performed, and what structures/organs are present?

· What

type of neoplasm is present?

· What are

the size and histologic grade of the neoplasm?

· If the

patient received neoadjuvant chemo-therapy, what is the percentage of tumor

necrosis?

· Is there

any cortical penetration or soft tissue invasion?

· What is

the status of the soft tissue and bone margins of resection?

·

Is a skip lesion present?

Related Topics