Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Nervous system

Bacterial meningitis - Infections of the nervous system: Meningitis and encephalitis

Infections of the nervous system

Meningitis and encephalitis

Bacterial meningitis

Definition

Bacterial infection of the meninges (the tissues lining the brain and spinal cord).

Aetiology

The likely organism changes with age. In adults, the most common are Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae. Less common organisms include gram-negative bacilli (particularly as a hospital acquired infection) and Listeria in the elderly and immunocompromised. Predisposing factors include predisposition to streptococcal infection (e.g. asplenic patients), otitis media, alcoholism, skull fracture, neurosurgery or immunosuppression.

Pathophysiology

The organisms may spread directly from the nasopharynx, middle ear, the skull vault or haematogenously then crossing the blood-brain barrier. Once within the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the bacteria multiply rapidly. There is an acute inflammatory response to the bacteria with neutrophils and cytokine release, then endothelial dysfunction causing disruption of local blood flow, oedema, and ischaemia and cell death. Hydrocephalus, raised intracranial pressure, cranial nerve palsies or other neurological problems such as seizures may occur as a result. Neisseria meningitidis may cause meningitis, septicaemia or both simultaneously.

Clinical features

· Meningitis should be considered in all patients with a headache and fever. Patients may have a prodromal illness resembling ‘flu’.

· The symptoms may progress rapidly over hours, or a few days. The headache is generalised, and increases in intensity to severe. Associated symptoms include photophobia, confusion and non-specific symptoms such as malaise, nausea and vomiting, and neck pain.

· Examination often demonstrates neck stiffness (an inability to touch chin to chest passively or actively).

· Other signs of meningism are a positive Kernig sign (when the hip is kept flexed at 90◦ , knee extension causes pain or is resisted) or Brudzinski sign (spontaneous flexion of the hip when the neck is flexed). Patients are examined for a petechial rash which suggests N. meningitidis.

· There may be evidence of an underlying cause or origin for the infection.

Complications

Neurological and cerebrovascular complications include intracranial venous thrombosis, cerebral oedema and hydrocephalus. Septic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation occur in 8–10% of patients with meningococcal meningitis. N. meningitidis is also associated with adrenal haemorrhage (Waterhouse– Friderichsen syndrome) which is rapidly fatal.

Macroscopy/microscopy

Inflamed arachnoid mater, with exudate in the subarachnoid space which is rich in neutrophils. There may be oedema, focal infarction and congested vessels in the underlying brain tissue.

Investigations

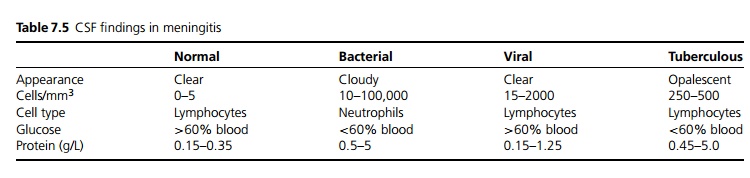

If there is no evidence of intracranial mass lesion, focal neurology, papilloedema or reduced consciousness, a lumbar puncture can be performed otherwise a CT brain is indicated prior to LP. CSF is sent urgently for protein, glucose, microscopy and culture (see Table 7.5). CSF pressure is characteristically raised. Other important tests include blood culture (up to 50% positive, if taken before antibiotics given), coagulation screen and blood glucose levels for comparison with CSF glucose. Low inflammatory markers (CRP and ESR) and low white blood counts do not exclude the diagnosis and are associated with a worse prognosis. PCR, ELISA and antigen testing are increasingly used.

Management

Treatment delay may be fatal, if the patient is severely un-well treatment should be commenced before performing LP/CT brain. CSF taken soon after antibiotics are given still demonstrates the causative organism in many cases.

· A broad-spectrum antibiotic such as a cephalosporin at high doses is initially recommended due to the increasing emergence of penicillin-resistant strepto-cocci. Once cultures and sensitivities are available, the course and choice of agent can be determined (ceftriaxone/cefotaxime for Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae, penicillin for N. menin-gitidis, and ampicillin for Listeria).

· Dexamethasone for 2–4 days which is commenced shortly before or at the time of giving antibiotics may reduce mortality and overall morbidity in adults and may reduce the incidence of hearing loss in children.

· Nasopharyngeal clearance may be recommended for the patient and household ‘kissing contacts’, e.g. with a quinolone or rifampicin. Cephalosporins provide good clearance of nasal carriage in the patient, but penicillins do not.

· Any underlying cause may need to be treated.

Vaccination

Vaccination with the H. influenzae B (HiB) vaccine has dramatically reduced this as a cause of meningitis in children. It is recommended in asplenic patients.

Meningococcal meningitis is most commonly of the type B meningococcus, for which there is no vaccine. However, the type C vaccine is used to reduce the chance of an epidemic when clusters occur and is now a routine childhood immunisation.

Conjugate Strep. pneumoniae vaccine (Prevenar®) is given to infants with chronic diseases, and Pneumovax® (live attenuated) is used in at risk patients.

Prognosis

Despite the advent of antibiotics, the mortality is still as high as 15–20%, with a significant proportion of survivors having persistent neurological abnormality. Poor prognostic markers include hypotension, confusion and seizures.

Related Topics