Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Anxiety, Anxiety Disorders, and Stress-Related Illness

Anxiety as a Response to Stress

ANXIETY AS A RESPONSE TO STRESS

Stress is the wear and tear that

life causes on the body (Selye,

1956). It occurs when a person has difficulty deal-ing with life situations,

problems, and goals. Each person handles stress differently: One person can

thrive in a situ-ation that creates great distress for another. For example,

many people view public speaking as scary, but for teach-ers and actors, it is

an everyday, enjoyable experience. Marriage, children, airplanes, snakes, a new

job, a new school, and leaving home are examples of stress-causing events.

Hans Selye (1956, 1974), an endocrinologist, identified the physiologic

aspects of stress, which he labeled the gen-eral

adaptation syndrome. He used laboratory animals to assess biologic system changes; the stages of the body’s physical

responses to pain, heat, toxins, and restraint; and, later, the mind’s

emotional responses to real or perceived stressors. He determined three stages

of reaction to stress:

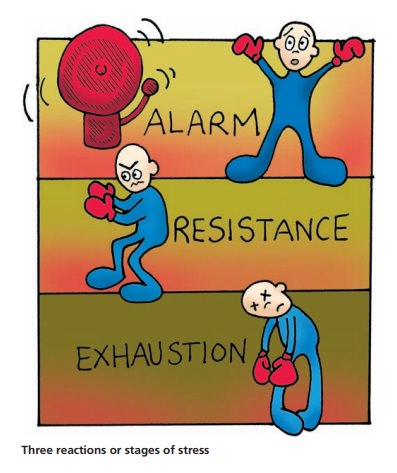

In the alarm reaction stage,

stress stimulates the body to send messages from the hypothalamus to the glands

(such as the adrenal gland, to send out adrenaline and norepinephrine for fuel)

and organs (such as the liver, to reconvert glycogen stores to glucose for

food) to pre-pare for potential defense needs.

·

In the resistance stage,

the digestive system reduces function to shunt blood to areas needed for

defense. The lungs take in more air, and the heart beats faster and harder so

it can circulate this highly oxygenated and highly nourished blood to the

muscles to defend the body by fight, flight, or freeze behaviors. If the

per-son adapts to the stress, the body responses relax, and the gland, organ,

and systemic responses abate.

·

The exhaustion stage

occurs when the person has re-sponded negatively to anxiety and stress: body

stores are depleted or the emotional components are not re-solved, resulting in

continual arousal of the physiologic responses and little reserve capacity.

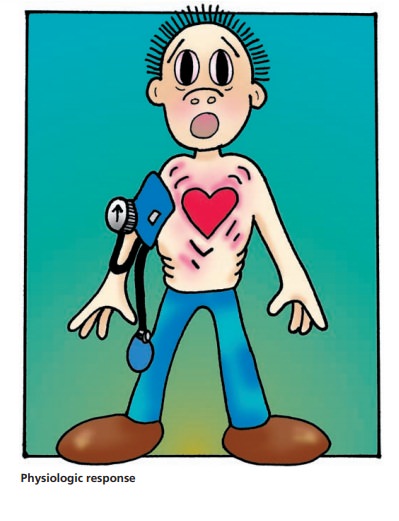

Autonomic nervous system responses to fear and anxi-ety generate

the involuntary activities of the body that are involved in self-preservation.

Sympathetic nerve fibers “charge up” the vital signs at any hint of danger to

prepare the body’s defenses. The adrenal glands release adrenalin

(epinephrine), which causes the body to take in more oxy-gen, dilate the

pupils, and increase arterial pressure and heart rate while constricting the

peripheral vessels and shunting blood from the gastrointestinal and

reproductive systems and increasing glycogenolysis to free glucose for fuel for

the heart, muscles, and central nervous system. When the danger has passed,

parasympathetic nerve fibers reverse this process and return the body to normal

operat-ing conditions until the next sign of threat reactivates the sympathetic

responses.

Anxiety causes uncomfortable cognitive, psychomotor, and

physiologic responses, such as difficulty with logical thought, increasingly

agitated motor activity, and elevated vital signs. To reduce these

uncomfortable feelings, the person tries to reduce the level of discomfort by

imple-menting new adaptive behaviors or defense mechanisms. Adaptive behaviors

can be positive and help the person to learn, for example, using imagery

techniques to refocus attention on a pleasant scene, practicing sequential

relax-ation of the body from head to toe, and breathing slowly and steadily to

reduce muscle tension and vital signs. Neg-ative responses to anxiety can

result in maladaptive behav-iors such as tension headaches, pain syndromes, and

stress-related responses that reduce the efficiency of the immune system.

People can communicate anxiety to others both ver-bally and

nonverbally. If someone yells “fire,” others around them can become anxious as

they picture a fire and the possible threat that represents. Viewing a

distraught mother searching for her lost child in a shopping mall can cause

anxiety in others as they imagine the panic she is experiencing. They can

convey anxiety nonverbally through empathy, which is the sense of walking in

another person’s shoes for a moment in time (Sullivan, 1952).

Examples of nonverbal empathetic communication are when the family

of a client undergoing surgery can tell from the physician’s body language that

their loved one has died, when the nurse reads a plea for help in a client’s

eyes, or when a person feels the tension in a room where two people have been

arguing and are now not speaking to each other.

Levels of Anxiety

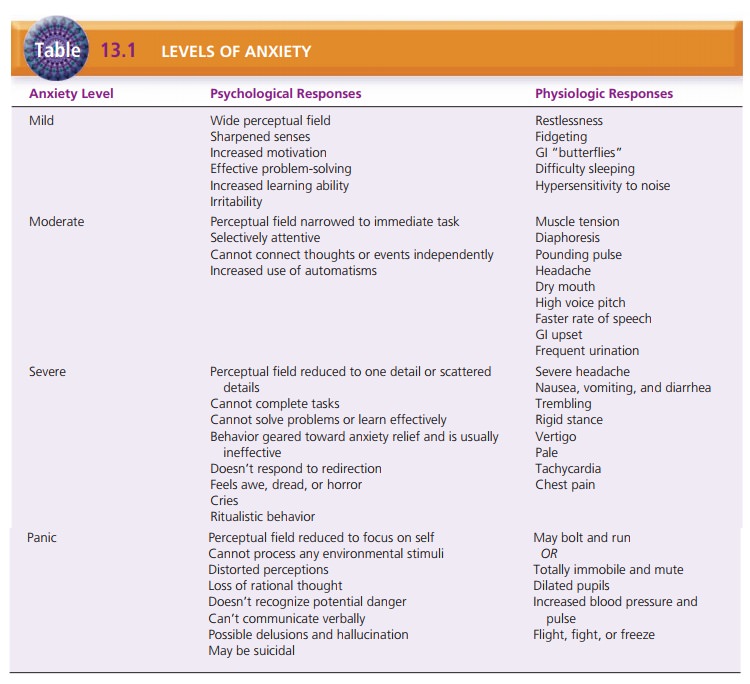

Anxiety has both healthy and harmful aspects depending on its

degree and duration as well as on how well the per-son copes with it. Anxiety

has four levels: mild, moderate, severe, and panic (Table 13.1). Each level

causes both physiologic and emotional changes in the person.

Mild anxiety is a sensation that something

is different and warrants special

attention. Sensory stimulation increases and helps the person focus attention

to learn, solve prob-lems, think, act, feel, and protect himself or herself.

Mild anxiety often motivates people to make changes or to engage in

goal-directed activity. For example, it helps students to focus on studying for

an examination.

Moderate anxiety is the disturbing feeling

that something is definitely wrong;

the person becomes nervous or agitated. In moderate anxiety, the person can

still process information, solve problems, and learn new things with assistance

fromothers. He or she has difficulty concentrating independently but can be

redirected to the topic. For example, the nurse might be giving preoperative

instructions to a client who is anxious about the upcoming surgical procedure.

As the nurse is teaching, the client’s attention wanders but the nurse can

regain the client’s attention and direct him or her back to the task at hand.

As the person progresses to severe

anxiety and panic, more primitive survival skills take over, defensive

responses ensue, and cognitive skills decrease significantly. A person with

severe anxiety has trouble thinking and reasoning. Muscles tighten and vital

signs increase. The person paces; is restless, irritable, and angry; or uses

other similar emotional–psychomotor means to release tension. In panic, the

emotional–psychomotor realm predominates with accompanying fight, flight, or

freeze responses. Adrenaline surge greatly increases vital signs. Pupils

enlarge to let in more light, and the only cognitive process focuses on the

person’s defense.

Working with Anxious Clients

Nurses encounter anxious clients and families in a wide variety of

situations such as before surgery and in emer-gency departments, intensive care

units, offices, and clin-ics. First and foremost, the nurse must assess the

person’s anxiety level because that determines what interventions are likely to

be effective.

Mild anxiety is an asset to the client and requires no direct

intervention. People with mild anxiety can learn and solve problems and are

even eager for information. Teach-ing can be very effective when the client is

mildly anxious.

In moderate anxiety, the nurse must be certain that the client is

following what the nurse is saying. The client’s attention can wander, and he

or she may have some difficulty concentrating over time. Speaking in short,

simple, and easy-to-understand sentences is effective; the nurse must stop to

ensure that the client is still taking in information correctly. The nurse may

need to redirect the client back to the topic if the client goes off on an

unrelated tangent.

When anxiety becomes severe, the client no longer can pay attention

or take in information. The nurse’s goal must be to lower the person’s anxiety

level to moderate or mild before proceeding with anything else. It is also

essential to remain with the person because anxiety is likely to worsen if he

or she is left alone. Talking to the client in a low, calm, and soothing voice

can help. If the person cannot sit still, walking with him or her while talking

can be effective. What the nurse talks about matters less than how he or she

says the words. Helping the person to take deep even breaths can help lower

anxiety.

During panic-level anxiety, the person’s safety is the pri-mary

concern. He or she cannot perceive potential harm and may have no capacity for

rational thought. The nurse must keep talking to the person in a comforting

manner, even though the client cannot process what the nurse is saying. Going

to a small, quiet, and nonstimulating envi-ronment may help to reduce anxiety.

The nurse can reas-sure the person that this is anxiety, that it will pass, and

that he or she is in a safe place. The nurse should remain with the client

until the panic recedes. Panic-level anxiety is not sustained indefinitely but

can last from 5–30 minutes.

When working with an anxious person, the nurse must be aware of his

or her own anxiety level. It is easy for the nurse to become increasingly

anxious. Remaining calm and in control is essential if the nurse is going to

work effectively with the client.

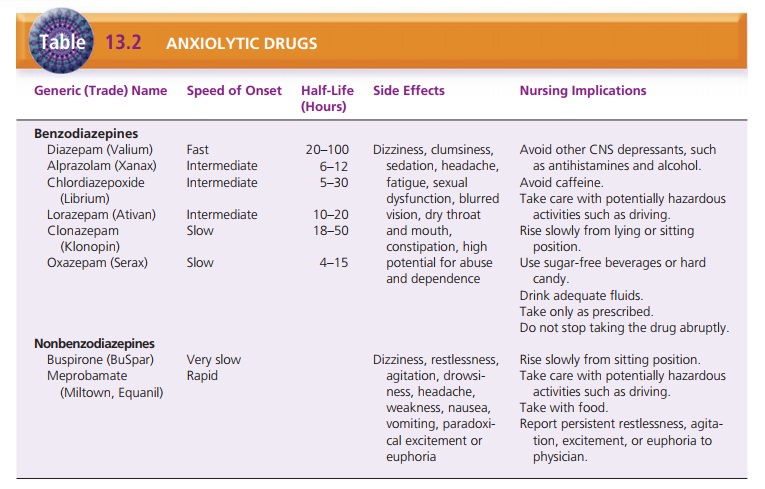

Short-term anxiety can be treated with anxiolytic medications

(Table 13.2). Most of these drugs are benzo-diazepines, which are commonly

prescribed for anxiety. Benzodiazepines have a high potential for abuse and

dependence, however, so their use should be short-term, ideally no longer than

4 to 6 weeks. These drugs are designed to relieve anxiety so that the person

can deal more effectively with whatever crisis or situation is caus-ing stress.

Unfortunately, many people see these drugs as a “cure” for anxiety and continue

to use them instead of learning more effective coping skills or making needed

changes.

Stress-Related Illness

Stress-related illness is a broad term that covers a spectrum of

illnesses that result from or worsen because of chronic, long-term, or

unresolved stress. Chronic stress that is repressed can cause eating disorders,

such as anorexia ner-vosa and bulimia. Repressed stress can cause physical

symptoms with no actual organic disease, called somatoform disorders . Stress

can also exacerbate the symptoms of many medical illness, such as hypertension

and ulcerative colitis. Chronic or recurrent anxiety resulting from stress may

also be diagnosed as an anxiety disorder.

OVERVIEW OF ANXIETY DISORDERS

Anxiety disorders are diagnosed when anxiety no longer functions as

a signal of danger or a motivation for needed change but becomes chronic and

permeates major por-tions of the person’s life, resulting in maladaptive

behav-iors and emotional disability. Anxiety disorders have many

manifestations, but anxiety is the key feature of each (American Psychiatric

Association [APA], 2000). Types of anxiety disorders include the following:

·

Agoraphobia with or without panic disorder

·

Panic disorder

·

Specific phobia

·

Social phobia

·

OCD

·

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

·

Acute stress disorder

·

Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Related Topics