Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiety Disorders: Panic Disorder With and Without Agoraphobia

Anxiety Disorders: Panic Disorder With and Without Agoraphobia

Anxiety Disorders: Panic Disorder With and Without

Agoraphobia

Definitions and Diagnostic Criteria

According to the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (Ameri-can Psychiatric Association,

2000), panic disorder is defined by recurrent and unexpected panic attacks. At

least one of these at-tacks must be followed by one month or more of:

·

persistent concern about having more attacks;

·

worry about the implications or consequences of the

attack; or

·

changes to typical behavioral patterns (e.g.,

avoidance of work or school activities) as a result of the attack

In addition, the panic attacks must not stem solely from the direct

effects of illicit substance use, medication, or a general medical condition

(e.g., hyperthyroidism, vestibular dysfunction) and are not better explained by

another mental disorder (e.g., such as social phobia for attacks that occur

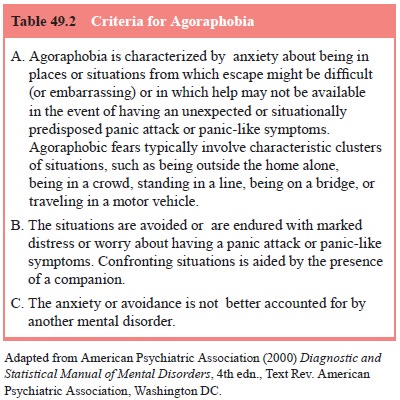

only in social situations). A diagnosis of panic disorder with agoraphobia is

warranted when the criteria for panic disorder are satisfied and accompanied by

agoraphobia.

Although panic attacks are a cardinal feature of panic dis-order and in

combination with agoraphobia (i.e., anxiety about be-ing in a place or a situation

that is not easily escaped or where help is not easily accessible if panic

occurs) are essential to a diagno-sis of panic disorder with agoraphobia, the

criteria sets for panic attacks and for agoraphobia are listed separately as

standalone noncodable conditions that are referred to by the diagnostic

cri-teria for panic disorder and agoraphobia without history of panic disorder.

Notwithstanding, accurate diagnosis is difficult without a proficient

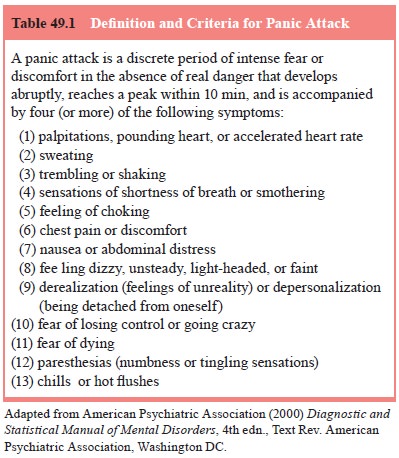

understanding of these features. Tables 49.1 and 49.2 show the DSM-IV-TR

criteria for panic attack and agoraphobia, respectively. While the criteria for

agoraphobia are generally straightforward, panic attacks can be difficult to

understand.

A number

of investigations indicate that people report hav-ing what they consider to be

a panic attack during or in association with actual physical threat (i.e., a

true alarm situation). It is, how-ever, important to distinguish between a fear

reaction in response to actual threat and a panic attack. In an attempt to do so,

the DSM-IV-TR has clarified that panic attacks occur “in the absence of real

danger”. Such attacks involve a paroxysmal occurrence of intense fear or

discomfort accompanied by a minimum of four of the 13 symptoms shown in Table

49.1. The DSM-IV-TR recognizes three characteristic types of panic attacks,

including those that are unex-pected (i.e., not associated with an identifiable internal

or external trigger and appear to occur “out of the blue”), situationally bound

(i.e.,

almost invariably occur when exposed to a situational trigger or when

anticipating it) and situationally predisposed (i.e., usually, but not

necessarily, occur when exposed to a situational trigger or when anticipating

it). The term limited symptom attacks is used to refer to panic-like

episodes comprising fewer than four symptoms.

Although unexpected panic attacks are required for a diag-nosis of panic

disorder, not all panic attacks that occur in panic dis-order are unexpected.

The occurrence of unexpected attacks can wax and wane and over the

developmental course of the disorder they tend to become situationally bound or

predisposed. Moreo-ver, unexpected panic attacks as well as those that are

situationally bound or predisposed can occur in the context of other psychiatric

disorders, including all of the other anxiety disorders, e.g., a per-son with

social phobia might have an occasional unexpected panic attack without the

other feature required to diagnose panic disor-der; a dog phobic might panic

whenever a large dog is encountered) and some general meda conditions. A clear

understanding of the

distinction between types of panic attacks outlined in the DSM-IV-TR

provides a foundation for diagnosis and differential diag-nosis. However,

consideration of other characteristics of panic – including duration of

attacks, frequency of attacks, number and intensity of symptoms, nature of

catastrophic thinking and mech-anism responsible for termination of an attack –

can be important in identifying exacerbating and controlling factors.

Related Topics