Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Mood Disorders: Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder: Treatment

Treatment

Antidepressant Treatment

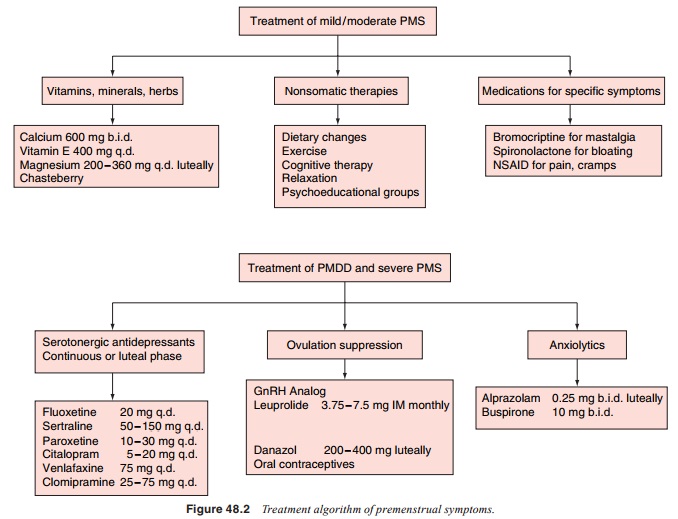

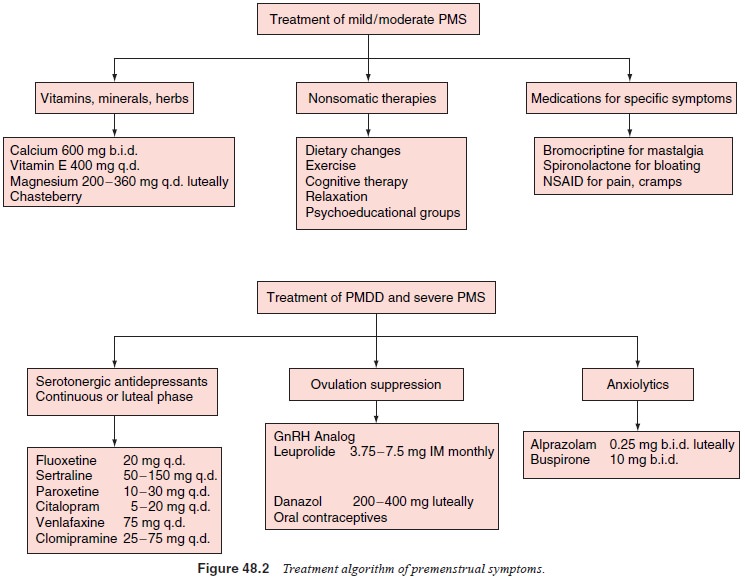

The treatment studies of SSRIs and venlafaxine in PMDD have suggested a

similar efficacy rate to treatment studies of SSRIs in major depressive

disorder, with 60 to 70% of women respond-ing to SSRIs compared with

approximately 30% of women re-sponding to placebo. In general, the effective

doses for all SSRIs are similar to the doses recommended for the treatment of

major depressive disorder (Figure 48.2) The efficacy of the continuous versus

intermittent dosing is equivalent.

A large RCT has reported that fluoxetine 20 mg/day dur-ing the luteal

phase only was superior to placebo in reducing premenstrual emotional and

physical symptoms in 252 women with PMDD (Cohen et al., 2002). There have not been reports of discontinuation

symptoms from these doses of SSRIs when abruptly stopped from the first day of

menses. There are no pub-lished studies to date of the efficacy of “symptom

onset” dosing of SSRIs, that is, administering SSRIs the postovulatory day that

premenstrual symptoms appear until menses. The efficacy of intermittent dosing,

as well as the findings from most SSRI tri-als that efficacy is achieved by the

first treatment cycle, has sug-gested a more rapid and different mechanism of

action of SSRIs in PMDD compared with its effect in major depressive disorder,

which typically takes 2 to 6 weeks. As discussed above, it has been

hypothesized that the rapid improvement of premenstrual symptoms by SSRIs may

be due to an increase in allopregna-nolone levels. The selective superiority of

serotonergic antide-pressants for PMDD is compatible with the postulated

serotonin dysfunction in PMDD.

Most SSRI trials have been 6 months or less in duration, so

efficacy-based long-term treatment recommendations do not ex-ist. Clinically,

many women note the recurrence of premenstrual symptoms after SSRI

discontinuation and many clinicians treat women over a long period of time. As

reviewed, a few open stud-ies report maintenance of SSRI efficacy over a couple

of years (Yonkers, 1997). Studies are needed to identify whether or not some

women develop tolerance to the SSRI and need a higher dose over time and

whether or not some women stay in remission for a period of time following SSRI

discontinuation.

Ovulation Suppression Treatments

Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists suppress ovulation by downregulating GnRH receptors in the hypothalamus, leading to decreased follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone release from the pituitary, resulting in decreased estrogen and progesterone levels. GnRH agonists are administered parenterally (e.g., subcutaneous monthly injections of goserelin, intramuscular monthly injections of leuprolide, daily intranasal buserelin) (see Figure 48.2). GnRH agonists lead to improvement in most emotional and physical premenstrual symptoms, with possible decreased efficacy for premenstrual dysphoria and severe premenstrual symptoms or for the exacerbation of chronic depression. After relief of PMS is achieved with a GnRH agonist, “add-back” hormone strategies have been investigated due to the undesirable medical consequences of the hypoestrogenic state resulting from prolonged anovulation. The addition of estrogen and progesterone to goserelin and leuprolide led to the reappearance of mood and anxiety symptoms. Since women with severe PMS and PMDD have an abnormal response to normal hormonal fluctuations, it is not surprising that women had the induction of mood and anxiety symptoms from the addition of gonadal steroids, reducing the benefit of the replacement strategy

Oral Contraceptives

Even

though oral contraceptives (OCs) are a commonly pre-scribed treatment for PMS,

there is minimal literature endorsing its efficacy. Anecdotally, women report

that oral contraceptives may benefit, worsen, or not affect their premenstrual

symptoms. The induction of dysphoria may be related to the type and dose of the

progestin component, the androgenic properties of the pro-gesterone, or to the

estrogen/progestin ratio (Kahn and Halbreich, 2001). A more recent RCT compared

an oral contraceptive to pla-cebo in 82 women with PMDD (Freeman et al., 2001).

Even though the OC containing ethinyl estradiol 30 µg and drospirenone 3 mg

improved most premenstrual symptoms, due in large part to a placebo response

rate of 40%, the OC was significantly more effi-cacious than placebo only in

decreasing food cravings, increased appetite and acne. Oral contraceptives have

been reported not to alter the response to SSRIs in women with PMDD.

Progesterone

The early assumption that PMS was due to a progesterone deficiency,

which has never been substantiated, led to luteal phase progesterone being one

of the earliest treatments of PMS in the literature. A recent systematic review

of published double-blind placebo-controlled randomized studies of luteal phase

progesterone (given as vaginal suppositories or oral micronized tablets) and

progestogens reported that there was no clinically meaningful difference

between all progesterone forms and placebo, although there was a small

statistically significant superiority of progesterone over placebo (Wyatt et al., 2001).

Other Medications

Alprazolam (administered during the luteal phase) has been re-ported to

be superior to placebo in most studies, and although it has a lower efficacy

rate than SSRIs, it is effective for premen-strual emotional symptoms.

Alprazolam should be tapered over the first few days of menses each cycle.

Buspirone at 25 mg/day during the luteal weeks has some efficacy.

Spironolactone has been reported to decrease premenstrual emotional and

physical symptoms. Bromocriptine has been reported to decrease premen-strual

breast.

Herbal Treatments and Dietary Supplementation

Most RCTs have shown little efficacy from herbal treatments and

therefore at this time no herbal treatment can be recommended. With respect to

dietary supplementation, calcium is reported to have a nearly 50% efficacy rate

for reducing the emotional and physical symptoms of the PMDD diagnostic

criteria, except for fatigue and insomnia, compared with 30% for placebo.

However, women with concurrent psychiatric illness were not clearly excluded,

and other treatments except for analgesics were allowed. The efficacy of

calcium was somewhat less in women who were also taking oral contraceptives

(Thys-Jacobs et al., 1998). The

results of this study were notable, and calcium deserves further study. Like herbal preparation, there is a

paucity of data to support the efficacy of vitamin supplementation. have a

nearly 50% efficacy rate for reducing the emotional and physical symptoms of

the PMDD diagnostic criteria, except for fatigue and insomnia, compared with

30% for placebo. However, women with concurrent psychiatric illness were not

clearly excluded, and other treatments except for analgesics were allowed. The

efficacy of calcium was somewhat less in women who were also taking oral

contraceptives (Thys-Jacobs et al.,

1998). The results of this study were notable, and calcium deserves further study. Like herbal preparation, there is a

paucity of data to support the efficacy of vitamin supplementation.

Lifestyle Modifications and Psychosocial Treatments

Many lifestyle modifications and psychosocial treatments have been

suggested for PMS. Lifestyle modifications are often sug-gested through

self-help materials or in an individual or group psychoeducation format. A

recent study reported that a weekly peer support and professional guidance

group for four sessions was superior to waitlist control in terms of reducing

premen-strual symptoms. The treatment consisted of diet and exercise regimens,

self-monitoring and other cognitive techniques and environment modification

(Taylor, 1999). Studies have not been conducted on individual lifestyle or

psychosocial treatments to identify which components are most efficacious.

Dietary recommendations include decreased caffeine, fre-quent snacks or

meals, reduction of refined sugar and artificial sweeteners, and increase in

complex carbohydrates. Premen-strual increased appetite and carbohydrate

craving increases the availability of tryptophan in the brain, leading to

increased serot-onin synthesis. There is little data at this time supporting

dietary interventions.

Exercise is likewise a frequently recommended treatment for PMS that has

yet to be tested in a sample of women with prospectively-confirmed PMS or PMDD.

As reviewed, negative effect and other premenstrual symptoms improve with

regular exercise in women in general. Cognitive therapy (CT) is reported to be

a promising treatment for PMS. There are limited studies in the use of light

therapy, massage therapy, reflexology, chiropractic manipulation, acupuncture

and biofeedback.

Related Topics