Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Liver Disease

Anesthesia for Acute Hepatitis

ACUTE HEPATITIS

Acute hepatitis is usually the result of a

viral infec-tion, drug reaction, or exposure to a hepatotoxin. The illness

represents acute hepatocellular injury with a variable degree of cellular

necrosis. Clinical manifestations depend both on the severity of the

inflammatory reaction, and, more importantly, on the degree of necrosis. Mild

inflammatory reactions may present merely as asymptomatic elevations in the

serum transaminases, whereas massive hepatic necrosis presents as acute

fulminant hepatic failure.

Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is most commonly due to hepa-titis A, hepatitis B, or

hepatitis C viral infection. At least two other hepatitis viruses have also

been identified: hepatitis D (delta virus) and hepa-titis E (enteric non-A,

non-B). Hepatitis types and E are transmitted by the fecal-oral route, whereas

hepatitis types B and C are transmitted primarily percutaneously and by contact

with body fluids. Hepatitis D is unique in that it may be transmitted by either

route and requires the pres-ence of hepatitis B virus in the host to be

infective. Other viruses may also cause hepatitis, including Epstein–Barr,

herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, and coxsackieviruses.

Patients with viral hepatitis often have a 1-

to 2-week mild prodromal illness (fatigue, malaise, low-grade fever, or nausea

and vomiting) that may or may not be followed by jaundice. The jaundice

typically lasts 2–12 weeks, but complete recovery, as evidenced by serum

transaminase measurements, usually takes 4 months. Because clinical

manifes-tations overlap, serological testing is necessary to determine the causative

viral agent. The clinical course tends to be more complicated and prolonged

with hepatitis B and C viruses relative to other types of viral hepatitis.

Cholestasis may be a major

manifestation. Rarely, fulminant hepatic fail-ure (massive hepatic necrosis)

can develop.

The incidence of chronic active

hepatitis is 3% to 10% following

infection with hepati-tis B virus and at least 50% following infection with

hepatitis C virus. A small percentage of patients (mainly immunosuppressed

patients and those on long-term hemodialysis regimens) become asymp-tomatic

infectious carriers following infection with hepatitis B virus, and up to 30%

of these patients remain infectious with the hepatitis B surface anti-gen

(HBsAg) persisting in their blood. Most patients with chronic hepatitis C

infection seem to have very low, intermittent, or absent circulating viral

particles and are therefore not highly infective. Approximately 0.5% to 1% of

patients with hepatitis C infection become asymptomatic infectious car-riers,

and infectivity correlates with the detection of hepatitis C viral RNA in

peripheral blood. Such infectious carriers pose a major health hazard to

operating room personnel.

In addition to “universal precautions” for

avoiding direct contact with blood and secretions (gloves, mask, protective

eyewear, and not recapping needles), immunization of healthcare personnel is

highly effective against hepatitis B infection. A vac-cine for hepatitis C is

not available; moreover, unlike hepatitis B infection, hepatitis C infection

does not seem to confer immunity to subsequent exposure. Postexposure

prophylaxis with hyperimmune glob-ulin is effective for hepatitis B, but not

hepatitis C.

Drug-induced Hepatitis

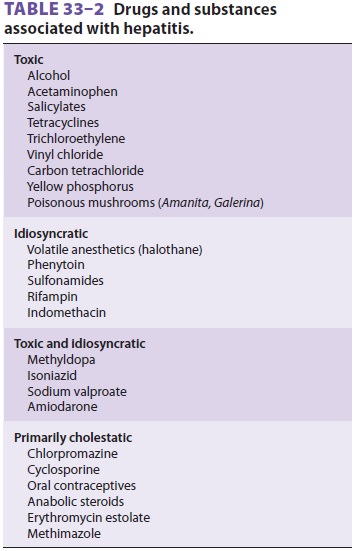

Drug-induced hepatitis (Table 33–2) can result from direct, dose-dependent toxicity of a drug or drug

metabolite, an idiosyncratic drug reaction, or a combination of these two

causes. The clinical course often resembles viral hepatitis, making diagnosis

difficult. Alcoholic hepatitis is probably the most common form of drug-induced

hepatitis, but the etiology may not be obvious from the history. Chronic

alcohol ingestion can also result in hepato-megaly from fatty infiltration of

the liver, which reflects impaired fatty acid oxidation, increased uptake and esterification

of fatty acids, and diminished lipoprotein synthesis and secretion.

Acetaminophen ingestion of 25 g or more usually results in fatal fulminant

hepatotoxicity. A few drugs, such as chlorpromazine and oral contracep-tives,

may cause cholestatic-type reactions . Ingestion of potent hepatotoxins, such

as carbon tetrachloride and certain species of

mushrooms (Amanita, Galerina),

also may result in fatal hepatotoxicity.

Because of the increased risk of perioperative

morbidity and mortality, patients with acute hepatitis should have elective

surgery postponed until the illness has resolved, as indicated by the

nor-malization of liver tests. In addition, acute alcohol toxicity greatly

complicates anesthetic management, and acute alcohol withdrawal during the

periopera-tive period may be associated with a mortality rate as high as 50%.

Only emergent surgery should be considered for patients presenting in acute

alcohol withdrawal. Patients with hepatitis are at risk of deterioration of

hepatic function and the develop-ment of complications from hepatic failure,

such as encephalopathy, coagulopathy, or hepatorenal syndrome.

Laboratory evaluation of the patient with

hep-atitis should include blood urea nitrogen, serum electrolytes, creatinine,

glucose, transaminases, bili-rubin, alkaline phosphatase, and albumin, platelet

count, and PT. Serum should also be checked for HBsAg whenever possible. A

blood alcohol level is useful if the history or physical examination is compatible

with ethanol intoxication. Hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis are not uncommon

and are usually due to vomiting. Concomitant hypo-magnesemia may be present in

chronic alcoholics and predisposes to cardiac arrhythmias. The eleva-tion in

serum transaminases does not necessarily correlate with the amount of hepatic

necrosis. The serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is generally higher than the

serum aspartate aminotransfer-ase (AST), except in alcoholic hepatitis, where

the reverse occurs. Bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase are usually only

moderately elevated, except with the cholestatic variant of hepatitis. The PT

is the best indicator of hepatic synthetic function. Persistent prolongation of

longer than 3 sec (INR > 1.5) fol-lowing administration of vitamin K is indicative of severe

hepatic dysfunction. Hypoglycemia is not uncommon. Hypoalbuminemia is usually

not pres-ent except in protracted cases, with severe malnutri-tion, or when

chronic liver disease is present.

If a patient with acute hepatitis must undergo an emergent operation,

the preanesthetic evalua-tion should focus on determining the cause and the

degree of hepatic impairment. Information should be obtained regarding recent

drug exposures, including alcohol intake, intravenous drug use, recent

transfusions, and prior anesthetics. The pres-ence of nausea or vomiting should

be noted, and, if present, dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities should be

anticipated and corrected. Changes in mental status may indicate severe hepatic

impair-ment. Inappropriate behavior or obtundation in alcoholic patients may be

signs of acute intoxica-tion, whereas tremulousness and irritability usually

reflect withdrawal. Hypertension and tachycardia are often also prominent with

the latter. Fresh fro-zen plasma may be necessary to correct a coagu-lopathy.

Premedication is generally not given, in an effort to minimize drug exposure

and not confound hepatic encephalopathy in patients with advanced liver

disease. However, benzodiazepines and thia-mine are indicated in alcoholic

patients with, or at risk for, acute withdrawal.

Intraoperative Considerations

The goal of intraoperative management is to

preserve existing hepatic function and avoid factors that may be detrimental to

the liver. Drug selection and dos-age should be individualized. Some patients

with viral hepatitis may exhibit increased central ner-vous system sensitivity

to anesthetics, whereas alco-holic patients will often display cross-tolerance

to both intravenous and volatile anesthetics. Alcoholic patients also require

close cardiovascular monitoring, because the cardiac depressant effects of

alcohol are additive to those of anesthetics; moreover, alcoholic

cardiomyopathy is present in many alcoholic patients.

Inhalation anesthetics are generally

preferable to intravenous agents because most of the latter are dependent on

the liver for metabolism or elimina-tion. Standard induction doses of

intravenous induction agents can generally be used because their action is terminated

by redistribution rather than metabolism or excretion. A prolonged duration of

action, however, may be encountered with large or repeated doses of intravenous

agents, particularlyopioids. Isoflurane and sevoflurane are the volatile agents

of choice because they preservehepatic blood flow and oxygen delivery. Factors

known to reduce hepatic blood flow, such as hypo-tension, excessive sympathetic

activation, and high mean airway pressures during controlled ventila-tion,

should be avoided. Regional anesthesia, includ-ing major conduction blockade,

may be employed in the absence of coagulopathy, provided hypotension is

avoided.

Related Topics