Chapter: Forensic Medicine: Toxicology and alcohol

Alcohol: Pharmacological effect

Pharmacological effect

General

The effect that alcohol has on the psyche, both

pleasant and unpleasant, is well-known. What is less well-known is that

alcohol, in different quantitiesfor different people, is a toxic drug. Alcohol

has both an acute and chronic effect on various organs of the body, including

the brain, heart, lungs, liver, the gastro-intestinal, genito-urinary and

endocrine systems.

a Nervous system

The damage that alcohol causes to the central

and peripheral nervous systems is of particular importance when it comes to the

driving of vehicles, as the following quote (Shaw: 1978) makes clear:

The exact mode of action of alcohol on the central nervous system is

unclear and its study complex. The effects of acute administration of alcohol

are often quite at variance with the effects of chronic administration and the

effects caused by a steady blood-alcohol level are often very different from

the effects caused by a changing blood-alcohol level. The rate of change may

itself be an important factor. Individual variation on whatever basis it may

rest is also important. Not only do we find that effects in the naõÈve subject

are very different from effects in the alcohol sophisticate, but it is well

known that all alcoholics do not suffer all the complications of alcoholism and

indeed some suffer none.

It appears that alcohol modifies the quality of

nerve-impulse transmission by stimulating the naturally occurring

nerve-transmission inhibitor, GABA, (gamma-amino-butyric acid) in the grey

matter of the brain. Drugs like Valium and barbiturates mimic this effect.

Similarly, cross-tolerance between these drugs and alcohol, when one of them is

used over a long period, is frequently observed. Furthermore, different types

of nerve cells display different degrees of sensitivity to the effects of

alcohol and these drugs.

The fact that we have stressed the complexity of

the effects of alcohol on the body should make it clear that many factors, as

yet poorly understood, could influence the response elicited by alcohol, and

that extreme caution should be exercised before expressing any final opinion on

individual behaviour and responses of the users of alcohol. In the early stages

of intoxication it is the loss of the inhibitory effect exercised by the higher

centres over the lower centres which accounts for the characteristic

behavioural changes such as the feeling of euphoria and the excessive

self-confidence which is out of all proportion to reality (Shaw: 1978).

It produces loss of emotional restraint and diminishes the inhibitions

which civilisation imposes on human conduct. Because in a social environment

many people become more active, both in speech and manner, it is widely (but

incorrectly) regarded as a stimulant.

The effect of alcohol on the nervous system is,

however, essentially depression of function, the extent of which depends on the

amount of alcohol working in on the brain cells, and the susceptibility of

these cells (or groups of cells) to alcohol. The cortical brain cells

(responsible for the higher functions) generally display the effect of alcohol

far sooner than those of the lower centres in the basal ganglia and the

midbrain. As blood-alcohol and thus brain-alcohol levels rise, more functions

of the nervous system are impaired, until co-ordination is drastically disturbed

and unconsciousness ensues. Deathcould follow due to depression of the

respiratory and later the circulatory control centres. It is said that alcohol

is in fact the most powerful depressant of the central nervous system that is

freely available without a doctor's prescription.

Furthermore, it seems as if alcohol prolongs

recovery time of the retinal response, and this is probably due to a direct

effect on the nerve cells of the retina.

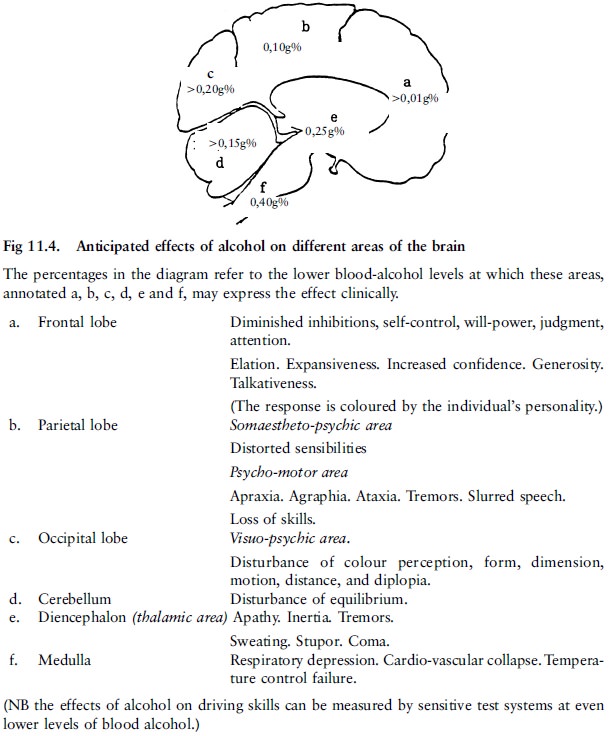

In broad terms it can be said that the effect of

alcohol on the highly developed frontal cortical regions of the brain

(responsible, inter alia, for conscious thought) can be seen with blood-alcohol

levels as low as 0,01%. This is manifested through altered judgment,

talkativeness and lack of attention (Shaw: 1978).

Early behavioural effects are much modified by personality factors in

the user and by the environmental situation in which drink is taken. In lively

company, disinhibition is the rule. The drinker becomes less self-conscious,

more talkative and less discreet. Judgment and restraint rapidly go and there

is loss of emotional control, giving rise to the humorous observation that the

super-ego is readily soluble in alcohol. As the blood level rises, thinking

becomes slowed and superficial and learning and retention become faulty. Less

attention is paid to stimuli so that internal stimuli such as hunger and pain

are ignored, sometimes with dire consequences. It becomes more difficult to

attend and respond to external stimuli. Events at the periphery are ignored and

only the immediate situation is given attention. This impaired psychological

state is usually accompanied by feelings of increased confidence and skill.

b Muscular system

The detrimental effect on muscle activity is due

to poor control by the central nervous system (and the decrease in impulse

conduction and transmission) over the use and co-ordination of muscle

potential, rather than to any direct impact on muscle strength itself.

Factors affecting pharmacological effect

The pharmacological effect of alcohol can be

modified by a number of congenital and acquired factors, which could partly

account for the different reactions of individuals to alcohol. One of these is

the elimination rate.

Certain organic, functional and degenerative

diseases could render the brain cells or parts of the brain more susceptible to

the intoxicating effect of alcohol. Severe liver disease, such as alcoholic

cirrhosis, can have a significant effect on the distribution and elimination of

drugs, including alcohol, and this makes it difficult to predict how such a

person will respond to alcohol or drugs in any dosage.

Degrees of intoxication: clinical features

(See also Kemp 1986:29±31.)

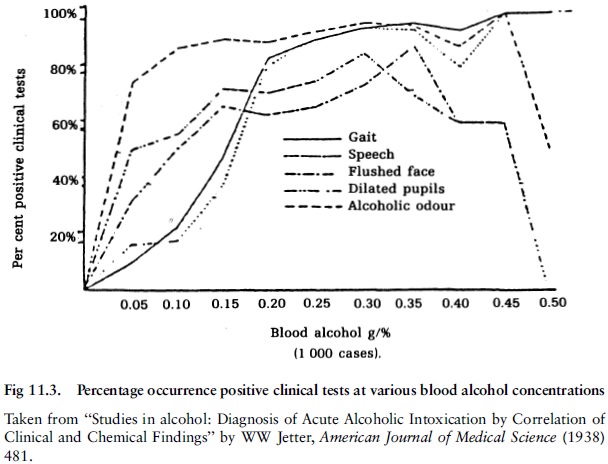

The clinical features of alcoholic intoxication

are mainly caused by its effect on the intellect, voluntary movement, speech

content, sensation, reflexes, cardio-vascular and gastrointestinal function.

It is customary to use various words and phrases

such as ``intoxicated'', ``under the influence'', ``drunk'' and ``paralytic''

to describe various states which may follow upon the consumption of alcohol.

These terms, as well as ``drunken driving'' and ``driving under the influence

of intoxicating liquor'' are at times used erroneously, as if they have the

same meaning.

It is suggested that the expression ``under the

influence'' be used to describe any abnormal mental or physical condition which

is the result of indulgence in any amount of alcohol, and which can range from

a state that deprives the subject of ``that clearness of intellect and control

which he would otherwise possess'' (Gradwohl 1954:971) to a state where death

from alcohol poisoning may be at hand. An individual under the influence of

alcohol could appear sober, that is, evidencing no noticeable effect at a

routine clinical examination, even to the skilled observer.

The clinically intoxicated person could

seemingly be:

·

lightly intoxicated

·

moderately intoxicated

·

heavily intoxicated

·

very heavily intoxicated

·

intoxicated to the extent of being stuporous to comatose

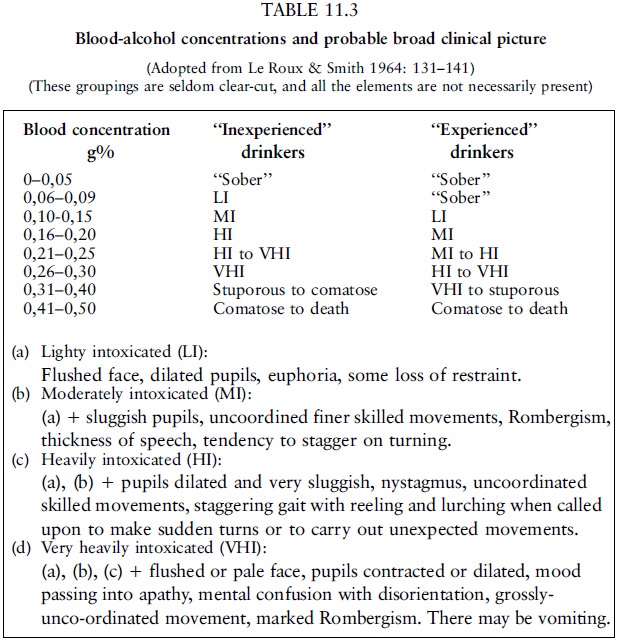

These degrees are not clearly distinguishable,

and rather represent a subtle progression of change in a broad spectrum of

behavioural and functional patterns. They tend to correspond broadly to

specific blood-alcohol concentrations, but wide variations are often seen

between the clinical picture and the BAC (blood alcohol concentration).

In individuals who are under the influence of

alcohol but appear sober, blood-alcohol levels of up to 0,08g% are often found.

Slight changes in neurological responses and behaviour compared to the

individual's normal responses may be detected by means of special tests not

normally used during the routine examinations, or by people who know the

subject well. The measured impairment detected by special tests is relative to

the subject's normal potential, and although not necessarily inferior to that

of another sober person, is nevertheless sufficient to materially affect

driving ability at levels of as low as 0,04g% or less.

a Lightly intoxicated

Clinically the subject may reveal signs of

mental impairment, unco-ordinated movements and speech defects. The face may be

flushed, the behaviour friendly, and the mood elevated. However, the reactions

are often coloured by the person's personality and surroundings. Euphoria or

depression, increased confidence, expansiveness, generosity, altered judgment

and absentmindedness may be present in differing degrees in different

individualsand in the same individual at different times at a given

blood-alcohol level. Clinical examinations generally reveal no other signs of

impairment. Blood-alcohol levels could reach 0,15g%. Subjectively the first

noticeable changes may be difficulty in visual accommodation and hearing,

especially when these functions are also impaired by disease or the ageing

process. The first movements to become visibly impaired are those requiring the

greatest skill.

b Moderately intoxicated

Clinical examination generally reveals evidence

of faculty impairment. The mood becomes less self-critical, and behavioural

changes, less tempered by reason, tend to be accentuated and often accompanied

by impulsive acts. The person is more reckless but sometimes also more

cautious. Unsteadiness when standing, turning and walking may be present in

varying degrees. Nystagmus (an involuntary rapid movement of the eyeball) is

usually present. The face is often flushed and the eyes bloodshot.

Blood-alcohol levels could reach 0,25g%, but generally range between 0,10 and

0,20g%.

c Heavily intoxicated

It is easy to detect functional impairment with

this degree of intoxication. Many aspects of behaviour are generally beyond

self-control and self-evaluation. The mind is dull and impairment of most

faculties is obvious. The faculties controlling the close co-ordination needed

for walking and other voluntary motor actions are markedly impaired.

Staggering, slurred and thick speech, the quality of which is shallow, confused

and illogical, is present. Movements are clumsy. Distance and position are

misjudged. The subject may attempt to conceal this impairment by performing

tasks more slowly. Pain and other sensations are dulled. Reflexes as tested

clinically are depressed and reaction time prolonged. The pupils become dilated

and react sluggishly to light. Co-ordination of eye movement is impaired.

Balance is impaired. Heart rate can increase. If nausea or vomiting is present,

the subject could be pale. Although intoxication is obvious to the observer,

the cause may (as in all degrees of intoxication) be difficult to determine. Blood-alcohol

levels of up to 0,30g% and very occasionally even higher are found.

d Very heavily intoxicated

There are confusion and disorientation with

regard to both time and place, apathy, drowsiness and marked disruption of both

motor and functional co-ordination. Confusion, disorientation and supressed

sensibility, particularly when accompanied by nausea and vomiting, could mask

or resemble underlying organic pathology. Blood-alcohol levels even in excess

of 0,35g% are found.

e Stuporous to comatose

It can be very difficult to determine the cause

of the stupor or coma. Unconsciousness, slow respiration, weak cardiac action

and dilated pupils with marked depression of all reflex reactions may be caused

by many different intoxicants and a great variety of diseases. Blood-alcohol

levels of up to 0,45g% and on rare occasions even higher may be found.

At levels of 0,45g% stupor is to be expected and

at levels of around 0,50g%, coma or death. Death has occurred at levels of

0,40g% or even lower in cold conditions, but recovery has occurred with levels

as high as 0,70g%. The manner of dying is via deepening coma to respiratory

paralysis.

In habitual drinkers the behavioural

disturbances will be less marked at all blood-alcohol levels, although it is

said that the alcoholic is no less susceptible than the non-alcoholic to

potentially lethal blood-alcohol levels. The well-known phenomenon of a

hangover (headache, fatigue and dizziness) can be caused by the alcohol or

acetaldehyde or both or by substances formed during the fermentation process.

It has also been suggested that most of the symptoms of a hangover can be the

result of hypoglycaemia. Blood-glucose levels are generally lower in both the

normal alcohol-naõÈve and the chronic alcoholic, but true hypoglycaemia is

rarely found the morning after.

In a recent study no correlation was found

between the impairment of psychomotor skills necessary for driving and the

intensity of the hangover, although irritability caused by the hangover could

lead to carelessness. Drugs, such as codeine compounds, taken to relieve the

symptoms of the hangover, could affect driving skill due to their psychoactive

effect.

Related Topics