Early Resistance to British Rule - South Indian Rebellion 1801 | 11th History : Chapter 18 : Early Resistance to British Rule

Chapter: 11th History : Chapter 18 : Early Resistance to British Rule

South Indian Rebellion 1801

South Indian Rebellion 1801

The victory over Tipu and Kattabomman had released

British forces from several fronts to target the fighting forces in

Ramanathapuram and Sivagangai. Thondaiman of Pudukottai had already joined the

side of the Company. The Company had also succeeded in winning the support of

the descendent of the former ruler of Sivagangai named Padmattur Woya Thevar.

Woya Thevar was recognised by the Company as the legitimate ruler of

Sivagangai. This divisive strategy split the royalist group, eventually

demoralizing the fighting forces against the British.

In May 1801 a strong detachment under the command

of P.A. Agnew commenced its operations. Marching through Manamadurai and

Partibanur the Company forces occupied the rebel strongholds of Paramakudi. In

the clashes that followed both sides suffered heavy losses. But the fighters’

stubborn resistance and the Marudu brothers’ heroic battles made the task of

the British formidable. In the end the superior military strength and the able

commanders of the British army won the day. Following Umathurai’s arrest Marudu

brothers were captured from the Singampunary hills, and Shevathiah from

Batlagundu and Doraiswamy, the son of Vellai Marudu from a village near

Madurai. Chinna Marudu and his brother Vellai Marudu were executed at the fort

of Tiruppatthur on 24 October 1801. Umathurai and Shevathiah, with several of

their followers, were taken to Panchalamkurichi and beheaded on 16 November

1801. Seventy three rebels were banished to Penang in Malaya in April 1802.

Theeran Chinnamalai

The Kongu country comprising Salem, Coimbatore,

Karur and Dindigul formed part of the Nayak kingdom of Madurai but had been

annexed by the Wodayars of Mysore. After the fall of the Wodayars, these

territories together with Mysore were controlled by the Mysore Sultans. As a

result of the Third and Fourth Mysore wars the entire Kongu region passed into

the hands of the English.

Theeran Chinnamalai was a palayakkarar of Kongu

country who fought the British East India Company. He was trained by the French

and Tipu. In his bid to launch an attack on the Company’s fort in Coimbatore

(1800), Chinnamalai tried taking the help of the Marudu brothers from

Sivagangai. He also forged alliances with Gopal Nayak of Virupatchi; Appachi

Gounder of Paramathi Velur; Joni Jon Kahan of Attur Salem; Kumaral Vellai of

Perundurai and Varanavasi of Erode in fighting the Company.

Chinnamalai’s plans did not succeed as the Company

stopped the reinforcements from the Marudu brothers. Also, Chinnamalai changed

his plan and attacked the fort a day earlier. This led to the Company army

executing 49 people. However, Chinnamalai escaped. Between 1800 and July 31,

1805 when he was hanged, Chinnamalai continued to fight against the Company.

Three of his battles are important: the 1801 battle on Cauvery banks, the 1802

battle in Odanilai and the 1804 battle in Arachalur. The last and the final one

was in 1805. During the final battle, Chinnamalai was betrayed by his cook

Chinnamalai and was hanged in Sivagiri fort.

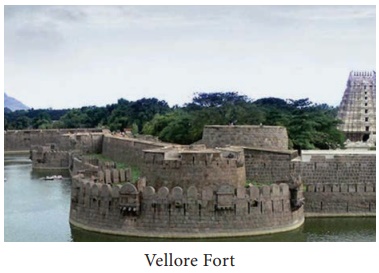

Vellore Revolt (1806)

Vellore Revolt 1806 was the culmination of the

attempts of the descendents of the dethroned kings and chieftains in south

India to throw of the yoke of the British rule. After the suppression of revolt

of Marudu brothers, they made Vellore the centre of their activity. The

organizers of an Anti-British Confederacy continued their secret moves, as a

result of which no fewer than 3,000 loyalists of Mysore sultans had settled

either in the town of Vellore or in its vicinity. The garrison of Vellore

itself consisted of many aggrieved persons, who had been reduced to dire

straits as a sequel to loss of positions or whose properties had been

confiscated or whose relatives were slain by the English. Thus the Vellore Fort

became the meeting ground of the rebel forces of south India. The sepoys and

the migrants to Vellore held frequent deliberations, attended by the

representatives of the sons of Tipu.

Immediate Cause

In the meantime, the English enforced certain

innovations in the administration of the sepoy establishments. They prohibited

all markings on the forehead which were intended to denote caste and religious,

and directed the sepoys to cut their moustaches to a set pattern. Added to

these, Adjutant General Agnew designed and introduced under his direct

supervision a new model turban for the sepoys.

The most obnoxious innovation in the new turban,

from the Indian point of view, was the leather cockade. The cockade was made of

animal skin. Pig skin was anathema to Muslims, while upper caste Hindus shunned

anything to do with the cow’s hide. To make matters worse the front part of the

uniform had been converted into a cross.

The order regarding whiskers, caste marks and earrings,

which infringed the religious customs of both Hindu and Muslim soldiers, was

justified on the grounds that, although they had not been prohibited previously

by any formal order, it had never been the practice in any well-regulated corps

for the men to appear with them on parade.

The first incident occurred in May 1806. The men in

the 2nd battalion of the 4th regiment at Vellore refused to wear the new

turban. When the matter was reported to the Governor by Col. Fancourt,

commandant of the garrison, he ordered a band of the 19th Dragoons (Cavalry) to

escort the rebels, against whom charges had been framed, to the Presidency for

a trial. The 2nd battalion of the 4th regiment was replaced by the 2nd

battalion of the 23rd regiment of Wallajahbad. The Court Martial tried 21

privates (a soldier of lower military rank)– 10 Muslims and 11 Hindus–, for

defiance. In pursuance of the Court Martial order two soldiers (a Muslim and a

Hindu) were sentenced to receive 900 lashes each and to be discharged from service.

Despite signals of protest the Government decided

to go ahead with the change, dismissing the grievance of Indian soldiers.

Governor William Bentinck also believed that the ‘disinclination to wear the

turban was becoming more feeble.’

Though it was initially claimed that the officers

on duty observed nothing unusual during the night of July 9, it was later known

that the English officer on duty did not go on his rounds and asked one of the

Indian officers to do the duty and Jameder Sheik Kasim, later one of the

principal accused, had done it. The leaders of the regiment who were scheduled

to have a field day on the morning of 10 July, used it as a pretext to sleep in

the Fort on the night of 9 July. The Muslim native adjutant contrived to post

as many of his followers as possible as guards within the Fort.

Jamal-ud-din, one of the twelve princes of Tipu

family, who was suspected to have played a key role in the revolt, kept telling

them in secret parleys that the prince only required them to keep the fort for

eight days before which time ten thousand would arrive to their support. He

disclosed to them that letters had been written to dispossessed palayakkarars

seeking their assistance. He also informed that there were several officers in

the service of Purniah (Tipu’s erstwhile minister) who were formerly in the

Sultan’s service and would undoubtedly join the standard.

Outbreak of Revolt

At 2:00 a.m. on 10 July, the sentry at the main

guard informed Corporal Piercy saying that a shot or two had been fired

somewhere near the English barracks. Before Piercy could respond, the sepoys

made a near simultaneous attack on the British guards, the British barracks and

the officers’ quarters in the Fort. In the European quarters the shutters were

kept open, as they were the only means of ventilation from the summer heat. The

rebels could easily fire the gun ‘through the barred windows on the Europeans,

lying unprotected in their beds.’ Fire was set to the European quarters.

Detachments were posted to watch the dwellings of the European officers, ready

to shoot anyone who came out. A part of the 1st regiment took possession of the

magazines (place where gun powder and ball cartridges stored). A select band of

1st Regiment was making their rounds to massacre the European officers in their

quarters.

Thirteen officers were killed, in addition to

several European conductors of ordnance. In the barracks, 82 privates died, and

91 were wounded.

Major Armstrong of the 16th native infantry was

passing outside the Fort when he heard the firing. He advanced to the glacis

and asked what the firing meant. He was answered by a volley from the ramparts,

killing him instantly. Major Coates, an officer of the English regiment who was

on duty outside the Fort, on hearing of the revolt tried to enter the Fort. As

he was unable to make it, he sent off an officer, Captain Stevenson of 23rd, to

Arcot with a letter addressed to Colonel Gillespie, who commanded the cavalry

cantonment there. The letter reached Arcot, some 25 km away, at 6 a.m. Colonel

Gillespie set out immediately, taking with him a squadron of the 19th dragoons

under Captain Young, supported by a strong troop of the 7th cavalry under

Lieutenant Woodhouse. He instructed Colonel Kennedy to follow him with the rest

of the cavalry, leaving a detachment to protect the cantonment and to keep up

the communication.

When Colonel Gillespie arrived at the Vellore Fort

at 9 a.m., he thought it prudent to await the arrival of the guns, since there

was continuous firing. Soon the cavalry under Kennedy came from Arcot. It was

about 10 o’Clock. The gate was blown open with the galloper guns of the 19th

dragoons under the direction of Lieutenant Blakiston. The troops entered the

place, headed by a squadron of the cavalry under Captain Skelton.

The Gillespie’s men were met by a severe crossfire.

In the ensuing battle, Colonel Gillespie himself suffered bruises. The sepoys

retreated. Hundreds escaped over the walls of the Fort, or threw down their

arms and pleaded for mercy. Then the cavalry regiment assembled on the parade

ground and resolved to pursue the fleeing soldiers, who were exiting towards

the narrow passage of escape afforded by the sally port. A troop of dragoons

and some native horsemen were sent round to intercept the fleeing soldiers. All

the buildings in the Fort were searched, and mutineers found in them pitilessly

slaughtered. Gillespie’s men wanted to enter the building and take revenge on

the princes, the instigators of the plot; but Lt. Colonel Marriott resisted the

attempt of the dragoons to kill Tipu’s sons.

According to J. Blakistan, an

eyewitness to Gillespie's atrocity, more than 800 bodies were carried out of

the fort. In W.J. Wilson's estimate 378 were jailed for involvement in the

revolt; 516 were considered implicated but not imprisoned. Based on depositions

before the Court of Enquiry, the Court Martial awarded death punishment and

banishment to select individuals, which were carried out by the commanding

officer of Vellore on 23 September 1806.

1st battalion of 1st Regiment

Blown from a gun ... 1 Havildar, 1 Naik

Shot ... 1 Naik, 4 sepoys

Hanged ... 1 Jamedar,

4 sepoys

Transported ... 3 Havildars, 2 Naiks, 1 sepoy.

2nd battalion of 23rd Regiment

Blown from a gun ... 2 Subedars, 2 Lascars

Hanged ... 2 Havildars, 1 Naik

(Source: W.J. Wilson, History of the Madras Army, vol. III, 1888-89).

Colonel Gillespie is said to have brought the Fort

under the possession of the English in about 15 minutes. Col. Harcourt

(Commanding Officer at Wallajahbad) was appointed to the temporary command of

Vellore on July 11 Harcourt assumed command of the garrison on 13 July, 1806

and clamped martial law. It was believed that the prompt and decisive action of

Gillespie put an end to ‘the dangerous confederacy, and had the fort remained

in the possession of the insurgents but a few days, they were certain of being

joined by fifty thousand men from Mysore.’

But the obnoxious regulations to which the soldiers

objected were withdrawn. The Mysore princes were ordered to be sent to

Calcutta, as according the Commission of Inquiry, their complicity could not be

established. They were removed from Vellore, on 20 August 1806. The higher

tribunals of the Home Government held the chief authorities of Madras, namely

the Governor, the Commander-in-Chief, and the Deputy Adjutant General,

responsible for the bungling and ordered their recall.

Vellore had its echoes in Hyderabad, Wallajahbad, Bangalore, Nandydurg, Palayamkottai, Bellary and Sankaridurg. Vellore Revolt had all the forebodings of Great Rebellion of 1857, if the word cartridge is substituted by cockade and Bahadur Shah and Nana Sahib could be read for Mysore Princes.

Related Topics