Early Resistance to British Rule - Great Rebellion 1857 | 11th History : Chapter 18 : Early Resistance to British Rule

Chapter: 11th History : Chapter 18 : Early Resistance to British Rule

Great Rebellion 1857

Great Rebellion 1857

Introduction

1857 has been a subject of much debate among

historians, both British and Indian. British imperialist historians dismissed

it a mutiny, an outbreak among soldiers. Indian historians who explored the

role of the people in converting a military outbreak into a rebellion raised

two questions to which the imperial historians have had no answer. If it was

only a military outbreak how to explain the revolt of the people even before

the sepoys at those stations mutinied? Why was it necessary to punish the

people with fine and hanging for complicity in acts of rebellion? Col.

Mallesan, the Adjutant General of the Bengal army in a pamphlet titled The Making of the Bengal Army remarked, ‘a military mutiny...speedily changed its character and became a national

insurrection’.

The historian Keene attributed the outbreak due to

operation of variety of factors: to the grievances of princes, soldiers and the

people, produced largely by the annexation and reforming zeal of Dalhousie. The

greased cartridge affair merely ignited the combustible matter which had

already accumulated. Edward John Thompson described the event ‘as largely a

real war of independence’. V.D. Savarkar, in his The War of Indian Independence,

published in 1909, argued that what

the British had till then described as merely mutiny was, in fact, a war of

independence, much like the American War of Independence. Despite the fact that

the English-educated middle class played no role in the rebellion, nationalist

historians championed this argument as the First War of Indian Independence.

Causes of the Rebellion

Territorial Aggrandisement

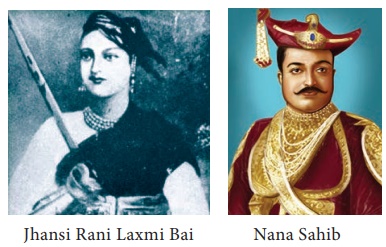

The annexation of Oudh and Jhansi by Dalhousie

employing the Doctrine of Lapse and the humiliating treatment meted out to Nana

Sahib, the last Peshwa’s adopted son produced much dissatisfaction. In the wake

of the Inam Commission (1852) appointed by Bombay government to enquire into the

cases of “land held rent-free without authority,” more than 21,000 estates were

confiscated. The land settlement in the annexed territories, particularly in

Oudh, adversely affected the interests of the talukdars, who turned against the

British. Moreover, in Oudh, thousands of inhabitants who depended on the royal

patronage and traders who were dealing in rich dresses and highly ornamented

footwear and expensive jewellery lost their livelihood. Thus Dalhousie through

his expansionist policy created hardship to a number of people.

Oppressive Land Revenue System

The rate of land revenue was heavy when compared

with former settlements. Prior to the British, Indian rulers collected revenue

only when land was cultivated. The British treated land revenue as a rent and

not a tax. This meant that revenue was extracted whether the land was

cultivated or not, and at the same rate. The prices of agricultural commodities

continued to crash throughout the first half of nineteenth century and in the

absence of any remission or relief from the colonial state, small and marginal

farmers as well as cultivating tenants were subject to untold misery.

Alienation of Muslim Aristocracy

and Intelligentsia

Muslims depended largely on public service. Before

the Company’s rule, they had filled the most honourable posts in former

governments. As commandants of cavalry some of them received high incomes. But

under the Company’s administration, they suffered. English language and western

education pushed the Muslim intelligentsia into insignificance. The abolition

of Persian language in the law courts and admission into public service by

examination decreased the Muslim’s chances of official employment.

Religious Sentiments

The Act of 1856 providing for enrolment of high

caste men as sepoys in the Bengal army stipulated that future recruits give up

martial careers or their caste scruples. This apart, acts such as the abolition

of sati, legalization of remarriage of Hindu widows, prohibition of infanticide

were viewed as interference in religious beliefs. In 1850, to the repugnance of

orthodox Hindus, the Lex Loci Act was passed permitting converts to

Christianity to retain their patrimony (right to inherit property from parents

or ancestors).

Further the religious sentiments of the sepoys –

Hindus and Muslims – were outraged when information spread that the fat of cows

and pigs was used in the greased cartridges. The Indian sepoys were to bite

them before loading the new Enfield rifle. This was viewed as a measure to

convert people to Christianity.

In every sense, therefore, 1857 was a climatic

year. The cartridge affair turned out to be a trigger factor for the rebellion.

The dispossessed, discontented rajas, ranis, zamindars and tenants, artisans

and workers, the Muslim intelligentsia, priests, and the Hindu pandits saw the

eruption as an opportunity to redress their grievances.

Course of the Revolt

The rebellion first began as a mutiny in

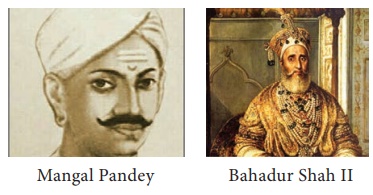

Barrackpore (near Calcutta). Mangal Pandey murdered his officer in January 1857

and a mutiny broke out there. In the following month, at Meerut, of the 90

sepoys who were to receive their cartridges only five obeyed orders. On 10 May

three sepoy regiments revolted, killed their officers, and released those who

had been imprisoned. The next day they reached Delhi, murdered Europeans, and

seized that city. The rebels proclaimed Bahadur Shah II as emperor.

By June the revolt had spread to Rohilkhand, where

the whole countryside was in rebellion. Khan Bahadur Khan proclaimed himself

the viceroy of the Emperor of India. Nearly all of Bundelkhand and the entire

Doab region were up in arms against the British. At Jhansi, Europeans were

massacred and Laxmi Bai, aged 22, was enthroned. In Kanpur Nana Sahib led the

rebels. About 125 English women and their children along with English officers

were killed and their bodies were thrown into a well. Termed as the Kanpur

massacre, this incident angered the British and General Henry Havelock, who was

sent to deal with the situation, defeated Nana Sahib the day after the

massacre. Neill, who was left there, took terrible vengeance and those whom he

regarded as guilty were executed. Towards the close of November Tantia Topi

seized Kanpur but it was soon recovered by Campbell.

The Lucknow residency, defended by Henry Lawrence

fell into the hands of rebels. Havelock marched towards Lucknow after defeating

Nana Sahib, but he had to retire. By the close of July John Nicholson sent by

John Lawrence to capture Delhi succeeded in capturing Delhi. The Mughal emperor

Bahadur Shah II now became a prisoner and his two sons and grandson were shot

dead after their surrender.

Resistance in Oudh was prolonged because of the involvement of talukdars as well as peasants in the revolt. Many of these taluqdars were loyal to the Nawab of Awadh, and they joined Begum Hazrat Mahal (the wife of the NawabWajid Ali Shah) in Lucknow to fight the British. Since a vast majority of the sepoys were from peasant families in the villages of Oudh, the grievances of the peasants had affected them. Oudh was the nursery of the Bengal Army for a long time. The sepoys from Oudh complained of low levels of pay and the difficulty of getting leave. They all rallied behind Begum Hazrat Mahal. Led by Raja Jailal Singh, they fought against the British forces and seized control of Lucknow and she declared her son, Birjis Qadra, as the ruler (Wali) of Oudh. Neill who wreaked terrible vengeance in Kanpur was shot dead in the street fighting at Lucknow. Lucknow could be finally captured only in March 1858.

Neill’s statue on the Mount Road,

Madras angered the Indian nationalists. The Congress Ministry of Rajaji

(1937-39) removed it and lodged it in the Madras Museum.

Hugh Rose besieged Jhansi and defeated Tantia Topi

early in April. Yet Lakshmi Bai audaciously captured Gwalior forcing

pro-British Scindia to flee. Rose with his army directly confronted Lakshmi

Bai. In this battle Lakshmi Bai died fighting admirably. Rose described Lakshmi

Bai as the best and bravest military leader of the rebels.

Gwalior was recaptured soon. In July 1858 Canning

announced the suppression of the “Mutiny” and restoration of peace. Tantia Topi

was captured and executed in April 1859.

Bahadur Shah II, captured in September 1857, was

tried and declared guilty. He was exiled to Rangoon (Myanmar), where he died in

November 1862 at the age of 87. With his death the Mughal dynasty came to an

end.

Effects of the Great Rebellion

Queen’s Proclamation 1858

A Royal Durbar was held at Allahabad on November 1,

1858. The proclamation issued by Queen Victoria was read at the Durbar by Lord

Canning, who was the last Governor General and the first Viceroy of India.

·

Hereafter India would be governed by and in the name of the British Monarch through a Secretary of

State. The Secretary of State was to be assisted by a Council of India

consisting of fifteen members. As a result, the Court of Directors and the

Board of Control of the East India Company were abolished and the Crown and

Parliament became constitutionally responsible for the governance of India. The

separate army of the East India Company was abolished and merged with that of

Crown.

·

Proclamation endorsed the treaties made by the Company with Indian princes, promised to respect their

rights, dignity and honour, and disavowed any ambition to extend the existing

British possessions in India.

·

The new council of 1861 was to have Indian nomination, since the Parliament thought the Legislative

Council of 1853 consisted of only Europeans who had never bothered to consult

Indian opinion and that led to the crisis.

·

The Doctrine of Lapse and the policy of annexation to be given up. A general amnesty (pardon) to be

granted to the rebels except those who directly involved in killing the British

subjects.

·

The educational and public works programmes (roads, railways, telegraphs, and irrigation) were

stimulated by the realization of their value for the movement of troops in

times of emergency.

·

Hopes of are vival of the past

diminished and the traditional structure of Indian society began to break

down. A Westernized English-educated middle class soon emerged with a

heightened sense of nationalism.

Related Topics