Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: Eczema and dermatitis

Atopic eczema

Atopic eczema

The

word ‘atopy’ comes from the Greek (a-topos: ‘without a place’). It was

introduced by Coca and Cooke in 1923 and refers to the lack of a niche in the

medical classifications then in use for the grouping of asthma, hay fever and

eczema. Atopy is a state in which an exuberant production of IgE occurs as a

response to common environmental allergens. Atopic subjects may, or may not,

develop one or more of the atopic diseases such as asthma, hay fever, eczema

and food allergies, and the prevalence of atopy is steadily rising.

In

Scotland, as many as 8% of children under 2 years have visible atopic eczema.

At least 1 school-child in 10 in Europe now suffers from atopic eczema and this

figure is still rising. The reasons for this are not yet clear, but are

unlikely to be a change in the genetic pool in the population. However, several

envir-onmental factors have been shown to reduce the risk of developing atopic

disease. These include having many older siblings, growing up on a farm, having

childhood measles and gut infections. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ unites these,

blaming changes in infant diets, the early use of antibiotics and a reduced

expo-sure to orofaecal and other infections for preventing normal immunological

maturation. The subsequent understimulation of gut-associated lymphoid tissue

may predispose to atopic sensitization to environ-mental allergens. The

circulating T lymphocytes of children destined to develop allergies shift to a

type II response and are poor at

producing γ-interferon

(IFN-γ); this

persists into late childhood.Early infections may lower the risk of allergy by

boosting the production of INF-γ.

One

promising but still experimental way of tack-ling these problems has emerged

recently, involving the use of probiotics, which are cultures of potentially

beneficial bacteria. They may reverse the increased intestinal permeability

that is characteristic of children with atopic eczema. In one recent study, the

perinatal administration of a Gram-positive probiotic (Lacto-bacillus

GG) halved the subsequent occurrence ofeczema in at-risk

infants.

Inheritance

A

strong genetic component is obvious, although affected children can be born to

clinically normal parents. The concordance rates for atopic eczema in

monozygotic and dizygotic twins are 86% and 21%, respectively; and atopic

diseases tend to run true to type within each family. In some, most of the

affected members will have eczema; in others respiratory allergy will

predominate. There is also a tendency for atopic diseases to be inherited more

often from the mother than the father. Environmental factors too are import-ant

and, not surprisingly, a simple genetic explanation has not yet been found.

Probably

the inheritance of atopic eczema requires genes that predispose to the state of

atopy itself, and others that determine whether it is asthma, eczema or hay

fever that occurs. One plausible gene for the inheritance of atopy itself lies

on chromosome 11q13. It encodes for the E subunit of the high affinity IgE

receptor, which is found both on mast cells (Fig. 8.1) and on

antigen-presenting cells in the skin. However, it has to be pointed out that

several groups have failed to confirm this linkage either in the families of

those with atopic eczema or respiratory allergy. Most recently, another gene

strongly linked to atopic eczema has been found on chromosome 3q21. It encodes

for clus-ter of differentiation (CD) antigens 80 and 86. Other candidates lie

on chromosomes 14q, 16p and 17p.

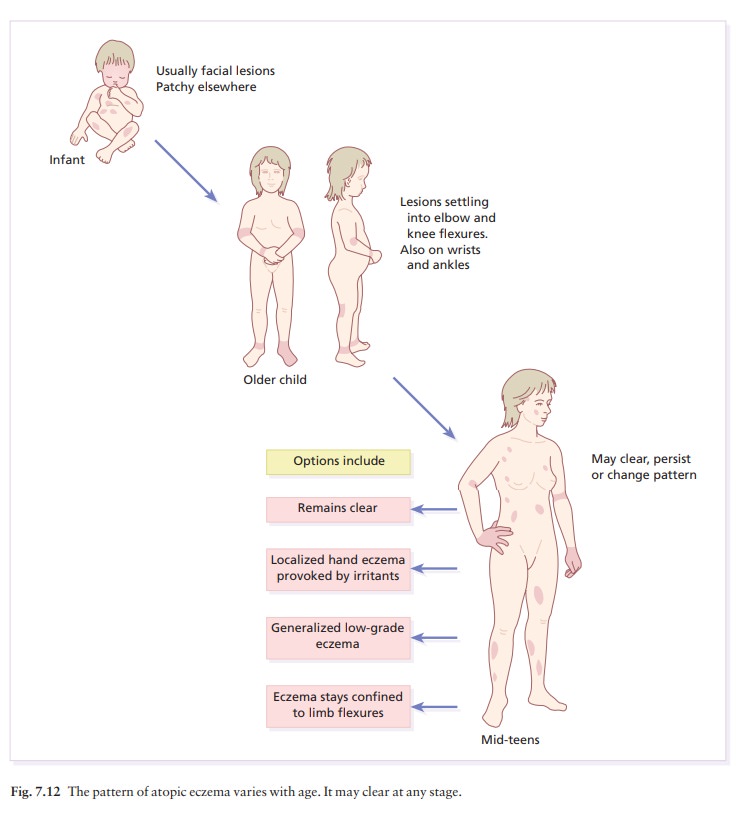

Presentation and course

Seventy-five

per cent of cases of atopic eczema begin before the age of 6 months, and 80–90%

before the age of 5 years. It affects at least 3% of infants, but the onset may

be delayed until childhood or adult life. Some 60–70% of children with atopic

eczema will clear by their early teens, although subsequent relapses are

possible. The distribution and character of the lesions vary with age (Fig.

7.12) but a general dryness of the skin may persist throughout life.

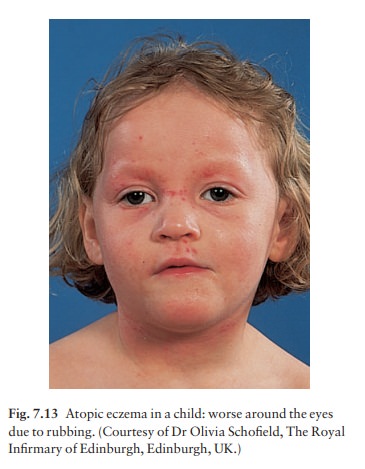

•

In infancy, atopic eczema tends to

be vesicular and weeping. It often starts on the face (Fig. 7.13) with a

non-specific distribution elsewhere, commonly spar-ing the napkin (diaper)

area.

•

In childhood, the eczema becomes

leathery, dry and excoriated, affecting mainly the elbow and knee flexures

(Fig. 7.14), wrists and ankles. A stubborn ‘reverse’ pattern affecting the

extensor aspects of the limbs is also recognized.

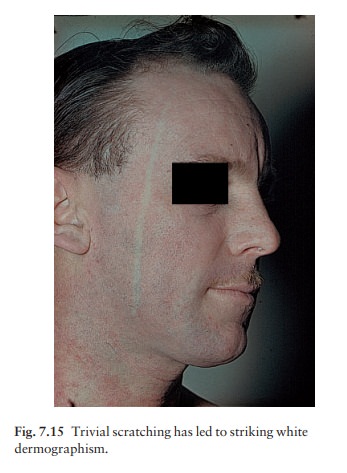

•

In adults, the distribution is as in

childhood with a marked tendency towards lichenification and a more widespread

but low-grade involvement of the trunk, face and hands. White dermographism

(Fig. 7.15) is often striking, but not diagnostic of atopic eczema.

The

cardinal feature of atopic eczema is itching; and scratching may account for

most of the clin

Affected children may sleep poorly, be hyperactive and sometimes

manipulative, using the state of their eczema to get what they want from their

parents. Luckily, the condition remits spontaneously before the age of 10 years

in at least two-thirds of affected children, although it may come back at times

of stress. Eczema and asthma may seesaw, so that while one improves the other

may get worse.

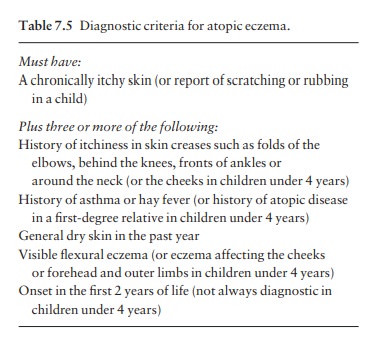

Diagnostic criteria

Useful

diagnostic criteria have been developed in the UK recently (Table 7.5).

Complications

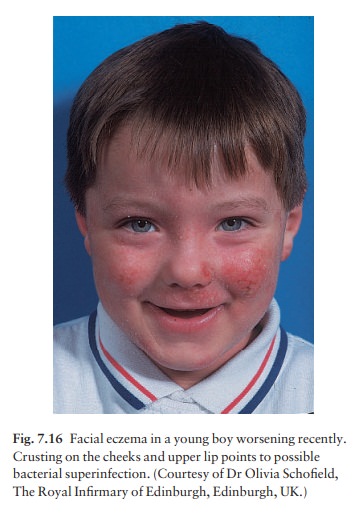

Overt bacterial infection is troublesome in many patients with atopic eczema (Fig. 7.16). They are also especially prone to viral infections, most dangerously with widespread herpes simplex (eczema herpeticum; Fig. 7.17), but also with molluscum contagiosum and warts.

Growth hormone levels

rise during deep sleep (stages 3 and 4), but these stages may not be reached

during the disturbed sleep of children with severe atopic eczema and as a

consequence they may grow poorly. The absorption of topical steroids can contribute

to this too.

Investigations

Prick

testing (see Fig. 3.10) demonstrates immediate-type hypersensitivity and is

helpful in the investigation of asthma and hay fever. However, the value of

prick testing in atopic eczema remains controversial. Often the finding of

multiple positive reactions, and a high IgE level, does little more than

support a doubtful clinical diagnosis without leading to fruitful lines of

treatment.

Treatment

Management

here is complex and should include the following.

•

Explanation, reassurance and

encouragement. Many patients and parents benefit from an introduction to the

National Eczema Society in the UK or the National Eczema Association for

Science and Education or the Inflammatory Skin Institute in the USA.

•

The avoidance of exacerbating

factors such as irrit-ants (e.g. woollen clothing next to the skin) and later

of careers such as hairdressing and engineering, which would inevitably lead to

much exposure to irritants. Also avoid extremes of temperature, and contact

with soaps and detergents.

•

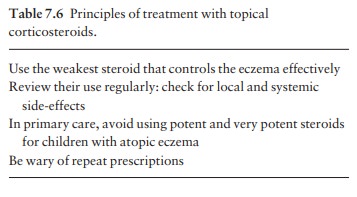

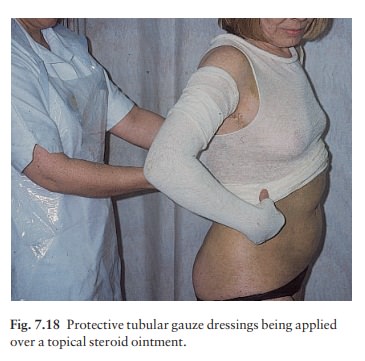

The judicious use of topical

steroids and other applications as for other types of chronic eczema (Table

7.6). A technique useful for extens-ive and troublesome eczema, particularly in

children, is that of ‘wet wrap’ dressingsasee above. A nurse who is expert in

applying such dressings is an asset to any practice (Fig. 7.18).

Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant produced by a streptomycete. It is used systemically in kidney, liver and heart trans-plantation. Trials of tacrolimus in ointment form have shown that it can be a quick and highly successful topical treatment for moderate to severe atopic eczema.

The preparation seems to be safe in use, with a transient

burning sensation being the most common side-effect; however, it decreases with

usage. Some use topical steroids briefly, to improve the eczema, before

starting tacrolimus ointment, hoping in this way to decrease the incidence and

severity of this burning sen-sation. Systemic absorption is low, and skin

atrophy is not a problem. Local infection might be troublesome and the

development of skin cancer, especially on exposed treated areas, is a concern

when the drug is used for prolonged periods. Perhaps more information and

experience are required before tacrolimus can be hailed as a revolutionary new

treatment for the treatment of inflammatory skin disordersabut the results so

far look highly impressive. Topical tacrolimus is now available as Protopic

ointment.

Pimecrolimus

is another topical immunosuppressant and a derivative of askamycin. Clinical

trials in moderate atopic eczema have been encouraging and it can be used in

patients older than 3 months. Its action is very similar to that of tacrolimus

and time will tell if either preparation is superior.

•

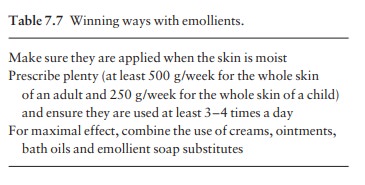

The regular use of bland emollients,

either directly to the skin or in the form of oils to be used in the bath. Some

of these can also be used as soap substitutes. A list of suitable preparations

is given in Formulary 1. Some rules governing the use of emollients are given

in Table 7.7.

•

Those with an associated ichthyosis

should gener-ally use ointments rather than creams.

• The scratch–itch cycle can often be interrupted by occlusive bandaging, e.g. with a 1% ichthammol paste bandage. Nails should be kept short.

•

Sedative antihistamines, e.g.

trimeprazine or hydro-xyzine are of

value if sleep is interrupted, but histamine release is not the main cause of

the itching, so the newer non-sedative anti-histamines help less than might be

expected.

•

Acute flares are often induced by

the surface pro-liferation of staphylococci, even without frank sepsis. A

month’s course of a systemic antibiotic, e.g. eryth-romycin, may then be

helpful.

• Allergen avoidance: prick tests confirm that most sufferers from atopic eczema have immediate hyper-sensitivity responses to allergens in the faeces of house dust mites. Sometimes, but not always, measures to reduce contact with these allergens help eczema. These measures should include encasing the mattress in a dustproof bag, washing the duvets and pillows every 3 months at a temperature greater than 55°C, and thorough and regular vacuuming in the bedroom, where carpets should preferably be avoided.

•

Do not keep pets to which there is

obvious allergy.

•

The role of diet in atopic eczema is

even more debatable, and treatments based on changing the diet of sufferers are

often disappointing. Similarly, it is not certain that the avoidance of dietary

allergens (e.g. cow’s milk and eggs) by a pregnant or lactating woman lessens

the risk of her baby developing eczema. It may still be wise to breastfeed children

at special risk for 6 months.

•

Routine inoculations are permissible

during quiet phases of the eczema. However, children who are allergic to eggs

should not be inoculated against measles, influenza and yellow fever.

•

Those with active herpes simplex infections

should be avoided to cut the risk of developing eczema herpeticum.

•

In stubborn cases UVB, UVA-1

(340–400 nm) or even PUVA therapy may be useful.

•

Cyclosporin: severe and unresponsive

cases may be helped by short courses under specialist supervision.

•

Chinese herbal remedies: properly

conducted trials have given promising results but difficulties remain. The

active ingredients within these complex mixtures of herbs have still not been

identified. We have some hope for the future but currently do not prescribe

these treatments for our patients.

Related Topics