Chapter: Plant Anatomy:An Applied Approach: Economic aspects of applied plant anatomy

Wood: present day

Wood: present day

Trunk wood

Most samples sent to Kew for anatomical identification consist wholly or mainly of wood. The samples are derived from many different sources and can be broadly divided into wood of recent origin and archaeological material. Furniture is made from woods carefully selected for their appear-ance and strength. Fashions have changed and it is common for certain spe-cies to have been selected for a period and then superseded by others. In addition, some woods were unavailable at certain periods. Consequently, by knowing which species were involved in the manufacture of antique fur-niture, it may be possible to date the piece, and occasionally the furniture expert may be able to get a good idea of who made it. Some craftsmen worked only with a carefully selected, characteristic range of woods. When repairs are necessary, it is also helpful to know which species should be used. The only way of being absolutely certain which woods were used is, in most in-stances, by making a microscopical study. Those who claim to be able to identify woods ‘on sight’ are either extremely experienced or over-bold, and many make errors.

The country of origin of carved wooden items can sometimes be estab-lished from the identity of the wood. Care must be taken because woods can be transported and then carved a long way away from their original sources. We have looked at items collected by Captain Cook on his voyages to try to determine where they could have come from, and this has proved suc-cessful. We once had for identification a wooden mask, carved in the like-ness of a dog. This proved to be alder wood and its association with North American Indians was confirmed.

The Trade Descriptions Act has again provided problems for builders and manufacturers where woods are concerned. If they state that a particu-lar wood has been used, this must be correct. The British Standards Institute has published a list of common names and the species from which the woods come, and this is the authoritative work which has to be followed

in the UK. The only way to be certain that the correct wood has been used is to compare sections of it with those from a standard reference collection of microscopic slides. On one occasion a door said to be made of solid mahogany was brought to the laboratory. It turned out to be laminated, and no true mahogany was found in it – in fact the middle layer of veneer was birch.

![]()

![]()

Properties of woods related to structure have been mentioned. We are occasionally asked to suggest substitute woods for some specialist purpose, when the supply of the normally used species has ceased. This can be difficult, but it is sometimes possible to suggest other species, which from their anatomical make-up might be expected to have similar properties.

Wood used as a backing for paintings, such as icons, is brought to the lab-oratory from time to time. The purpose in finding out the identity is often related to establishing the name of the artist, or the country of origin. We have examined the wood from a good many walking sticks; an amazingly wide range of species has been used for this purpose!

Preservation of wood is of considerable economic importance. A great deal of experimental anatomy is carried out in various parts of the world in order to establish the nature of the process of decay, the identity of the or-ganisms involved and the prevention of their degrading activities. The ‘sound’ wood has to be very carefully examined and described. Close obser-vations then have to be recorded on all stages of the decay processes and the action that the various organisms have on the wood.

Tree roots

Considerable damage, running into millions of pounds, is caused each year to buildings either directly or indirectly by the action of roots of trees or shrubs. There may be a number of different tree species near to the build-ings concerned. All or some of them might have roots beneath the founda-tions. It would be excessively expensive to try and trace the roots back to their parent trees by excavation. Fortunately it is possible to identify most roots of trees growing in the British Isles from aspects of their root anato-my, largely from features of the wood (secondary xylem). In some instances it is possible to identify to the species level, but more often only the genus can be identified, for example Quercus, oak, or Fraxinus, ash, and Acer, ma-ples and sycamore. In the Rosaceae, identifications can be made only to the subfamily level, for example Pomoideae and Prunoideae. Current research is aimed at finding additional characters in this family.

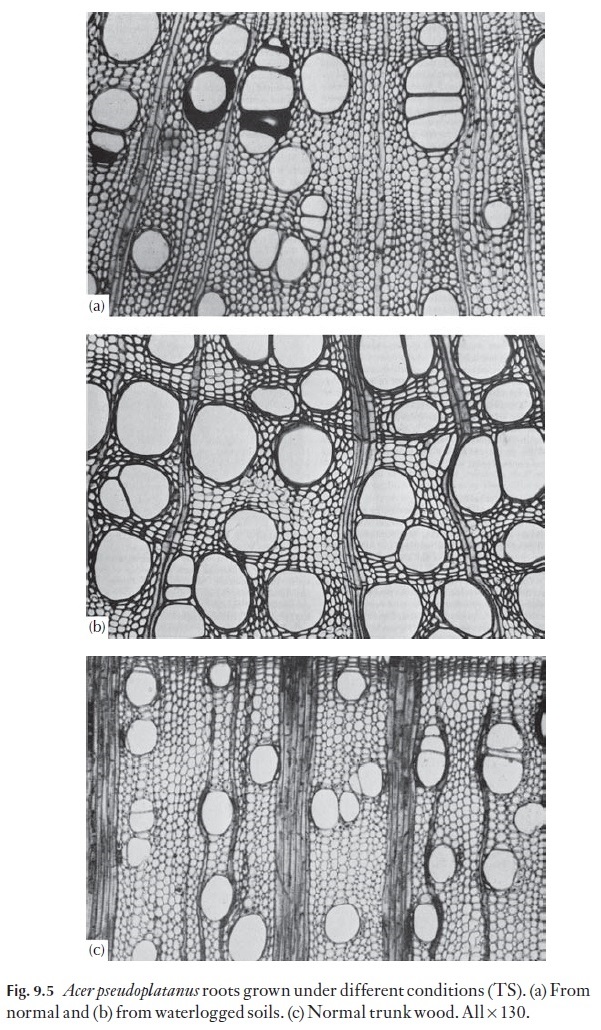

Sometimes it is not possible to get closer than the family, as for example in Salicaicae. In trunk wood, Salix and Populus can normally be separated because Salix usually has heterocellular rays and Populushomocellular rays. However, in the root wood this distinction does not hold. Indeed, root wood is often slightly dissimilar in its anatomy from trunk wood of the same spe-cies. This means that one cannot rely on the descriptions contained in ref-erence works on wood anatomy for accurate identification of roots. Root anatomy is also quite variable within a species, so the only way to be sure of making the proper identification is to compare the root sections with refer-ence microscope slides taken from a range of authenticated specimens. Figure 9.5 shows two roots of Acer pseudoplatanus (TS) grown under very different conditions and some normal trunk wood for comparison.

Related Topics