Chapter: Plant Anatomy:An Applied Approach: Economic aspects of applied plant anatomy

Taxonomic application - Economic aspects of applied plant anatomy

Taxonomic application

Systematic anatomy has a long history. From the early days of microscopy it has fascinated people who saw first the wide range of variations in plant anatomy, then began to recognize patterns of similarity, and eventually realized that in many instances, plants sharing large numbers of anatomical characters in common were probably closely related. This led to a series of attempts to work through the plant kingdom in an orderly way, and record what was present. For the angiosperms, in particular, this process led to the production of series of books. The work was started in earnest on the di-cotyledons, and when the first review was done the monocotyledons were started. In the present day, the work on dicotyledons is being revised, and completion of the first run through the monocotyledons is in progress. There is an enormous number of papers on angiosperm anatomy, and before setting out on new work it is sensible to find out what has already been published. In addition to the normal search engines, it is worth looking at the Plant Micromorphology Bibliographic Database on the web-site of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. This is important, because it goes far back into the literature and is kept up to date. Quoting from the web site ‘This is a unique bibliographic database maintained by the Micromor-phology Group (Anatomy Section and Palynology Unit). It contains over 95,000 articles and is probably the most comprehensive computerized index to higher plant micromorphology in existence. It covers most work published on plant anatomy in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and is regularly updated with new literature. All aspects of angiosperm and gymnosperm plant structure are covered, together with vegetative anatomy of pteridophytes. Common subject areas include ontogeny, ul-trastructure, techniques, palaeobotany, embryology and seed anatomy. In-ternet searches are available free of charge for scientific purposes. (If the searches are used in a publication, the “Micromorphology Group, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew” should be acknowledged.) Contact: pa.database@ kew.org.

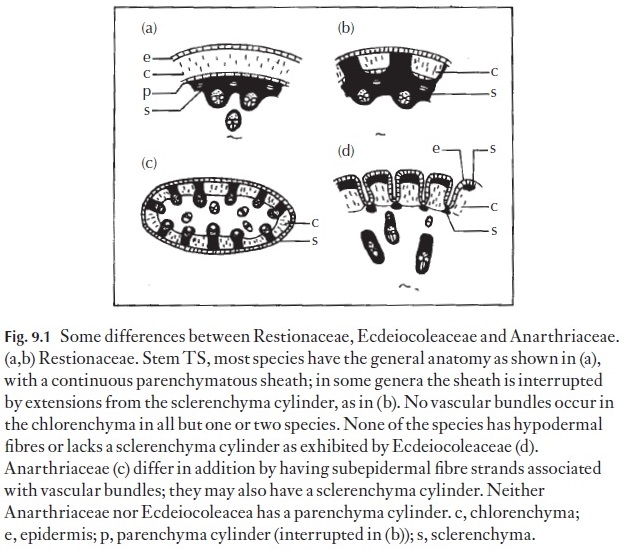

Anatomical data are easily applied to improving classifications and can often be used in making identifications. Take for example an instance where two new families were first recognized from their distinctive anatomy. The southwest Australian genera Anarthria and Ecdeiocolea were formerly treat-ed as members of the Restionaceae. An extensive anatomical survey of the family Restionaceae showed the two genera to be misfits. Consultation with a classical taxonomist proved that there also were taxonomically valid distinctions at the macromorphological level. Co-operative research re-sulted in two new families being recognized, Anarthriaceae and Ecdeio-coleaceae. Figure 9.1 summarizes some of the main differences. These families have subsequently been shown to be chemically distinct, and mo-lecular studies also support their separation. Thus, a hypothesis based upon macromorphology was tested using anatomy and other approaches and subsequently supported.

There are occasions when herbarium botanists find that it is difficult to ascribe a particular species or genus to a family, or where general affinities are suspected but there is insufficient evidence for them to place a taxon in a particular family. Here, additional anatomical evidence may be of help and

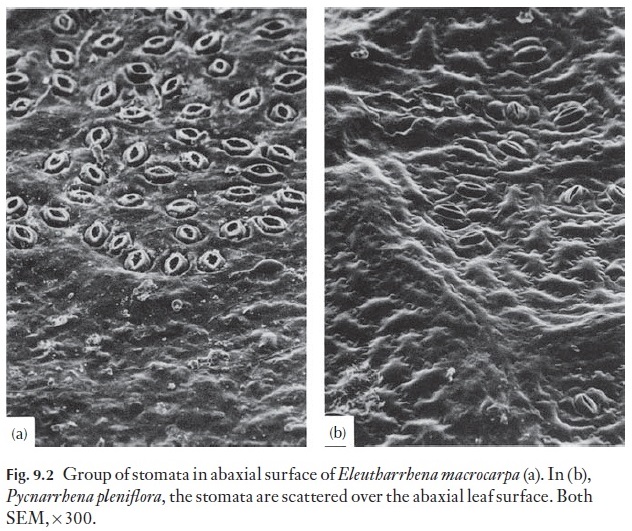

there are many times when little extra helpful information comes from the anatomy. Recently, tree leaf material collected in China was examined ana-tomically; although there were no flowers or fruits on the herbarium sheet, the taxonomist thought that he knew the close relatives of the plant in ques-tion. The anatomy confirmed his views that the plant was Pycnarrhena mac-rocarpa Diels (Menispermaceae). A further study of species from this genusled to the discovery that two distinct genera were involved and a new genus Eleutharrhena was named by Forman to include P. macrocarpa using evi-dence from morphology, anatomy and palynology. In Pycnarrhena, stomata are scattered over the abaxial leaf surface; in the Eleutharrhena the stomata are in distinct clusters (Fig. 9.2).

Of course, the correct classification of plants is important, but it is often of more direct importance to know exactly to which species a specimen be-longs. When flowers and fruits are absent, plant anatomists come into their own. Leaf fragments, wood and roots or twigs may have readily recogniza-ble features which can be seen with a lens, but more often than not, identity has to be confirmed with the microscope. It is possible, for example, to check the identity of non-flowering aloes by looking at the leaf surfaces under the SEM. The appearance of the leaf surface in these plants can also indicate which subgroup they belong to.

Related Topics