Chapter: Clinical Cases in Anesthesia : Cardiomyopathy Managed With A Left Ventricular Assist Device

What are the important anesthetic considerations for patients supported by LVADs?

What are

the important anesthetic considerations for patients supported by LVADs?

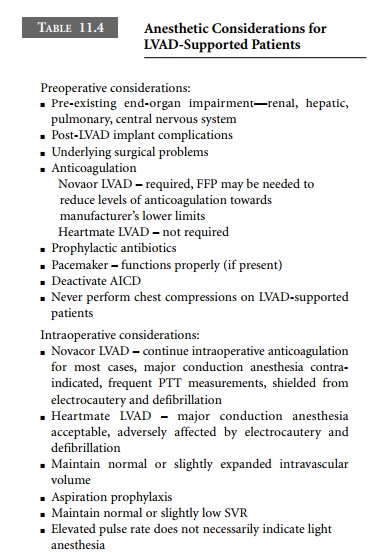

Preoperative Considerations

The preoperative clinical status of

LVAD-supported patients depends on multiple issues, such as the amount of

end-organ damage sustained during low-output states prior to ventricular assist

device (VAD) implantation, post-implantation complications, and underlying

surgical prob-lems. Many LVAD recipients are ambulatory and otherwise

uncompromised. Others experience varying degrees of renal, hepatic, pulmonary,

and/or central nervous system insufficiency. Preoperative evaluation of

neurologic dys-function and other major organ system problems is essen-tial.

Any further deterioration in the perioperative period may preclude full

recovery or disqualify a patient from later heart transplantation.

One of the most serious complications of

extracorpo-real circulation is thromboembolism, and LVADs are no exception. The

Heartmate’s blood chamber is designed with an antithrombogenic surface and

requires no formal anticoagulation; however, the Novacor’s polyurethane-lined

blood chamber mandates anticoagulation. Initially heparin is used and then

long-term warfarin therapy is commenced. International normalized ratios (INRs)

are maintained at 2.5–3.5 times normal. In elective situa-tions, Novacor

patients may discontinue warfarin therapy preoperatively and convert to

carefully monitored heparin infusions. In

most cases, heparin infusions should not be discontinued preoperatively. The majority of surgical procedures (except for neurosurgical

cases) can proceed safely in the presence of anticoagulation; however,

scrupu-lous attention to hemostasis is required intraoperatively. Fresh frozen

plasma or cryoprecipitate may be infused to decrease the level of

anticoagulation toward the lower limit of manufacturer’s recommendations.

Frequent partial thromboplastin time (PTT) measurements are important to

balance the dual potential complications of hemorrhage and thromboembolism.

Anesthesiologists must determine (perhaps in consultation with the sur-geon) a

safe anticoagulation regimen for the perioperative period.

Adherence to strict aseptic technique is

mandatory for all invasive procedures and prophylactic perioperative

antibiotics are routinely employed. Infection of an LVAD is a catastrophic

complication. They are very large foreign bodies that cannot be sterilized.

As with all critical life-support equipment in

the oper-ating room, an LVAD must be connected to a reliable power supply. Its

battery life is limited.

Preoperative considerations and practices

regarding pacemakers and AICDs are much the same in LVAD-supported patients as

in other patients. The pre-set pace-maker mode is ascertained and it is

interrogated for proper functioning. Usually, atrioventricular sequential

pacing will be in use (DDD or DOO mode), because this frequently preserves RV

output (and therefore LV filling) in these patients. Magnets should be available

in case of pacemaker malfunction. Modern pacemakers will usually convert to an

asynchronous mode (e.g., AOO, VOO, or DOO) when a magnet is applied, and should

revert to their prior programming when the magnet is removed. In any event,

pacemaker-dependent patients should have their device interrogated

postoperatively to assure proper func-tioning. Many, but not all LVAD patients

will have an AICD. Unipolar electrocautery emits a high-frequency signal that

could potentially be interpreted as ventricular fibrilla-tion, resulting in

unnecessary defibrillatory discharges. Consequently, AICDs are usually

deactivated in the imme-diate preoperative setting, assuming that a

defibrillator is immediately available. Where possible, bipolar electro-cautery

should be preferentially used. In an emergency situation, a magnet may be used

to deactivate the AICD. Most AICDs (Medtronics, St. Jude, Biotronik) will

remain deactivated as long as the magnet remains in place; however, a Guidant

AICD is permanently deactivated by application of a magnet. Removal and

subsequent reapplication of the magnet is required to reactivate a Guidant

AICD.

Cardiovascular collapse in LVAD patients is

treated with standard advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) protocols. However, one should never perform chest compressions

on a ventricular assist device

(VAD)-supported patient. Dislodgment of intracardiac cannulae will result in

imme-diate exsanguination and certain death. The Novacor is very well shielded, and will not be

affected by defibrillation or electrocautery. Unfortunately, the Heartmate may

be reset to a fixed-rate mode by electrocautery and potentially damaged by

external defibrillation. For Heartmate patients, preoperative consultation with

the physician managing the LVAD is advisable to discuss the implications of

electrocautery and external defibrillation.

Intraoperative considerations

Novacor’s requisite anticoagulation

contraindicates major conduction anesthesia, which relegates most patients to

general anesthesia. In some cases, sedation with local skin infiltration, or a

regional intravenous technique (Bier block) is appropriate. Heartmate patients

are not anticoagulated and remain potential candidates for major conduction

anes-thesia. Unfortunately, no specific recommendations exist regarding this

issue at the time of writing.

The pump’s pre-peritoneal location places the

LVAD-supported patient at increased risk for aspiration pneumoni-tis.

Consequently, “full stomach” precautions (e.g., gastric acid prophylaxis and

rapid sequence induction with cricoid pressure) should be considered.

Extubation criteria of the LVAD-supported patient are the same as in any other

patient.

The anesthetic drugs used should be appropriate

for the planned operation, and should take into account any alter-ations of

physiology resulting from insufficiency of, or prior injury to, major organ

systems. For example, it may be disadvantageous to use pancuronium or

vecuronium in the patient with renal insufficiency or biliary obstruction,

respectively. Succinylcholine may be contraindicated in patients with recent

cerebrovascular accidents. VADs do not specifically contraindicate any

particular anesthetic agents, but the anesthetic plan should consider the

poten-tially dysfunctional unassisted RV. Consequently, particular attention

should be paid to optimizing RV preload, after-load, and inotropic support as

required.

Long-term, implanted LVADs are typically set to

auto-matically eject as soon as the blood chamber is full. The faster the

device fills, the faster it pumps and the higher the pump output. Hypovolemia

results in slow pump filling, decreased LVAD output, and hypotension.

Consequently, the goal of fluid management is to maintain normal or slightly

elevated intravascular volume. Markedly increased systemic vascular resistance

(SVR) impairs forward flow, resulting in incomplete pump emptying, which leads

to stagnation of blood in the pump and increased risk of thrombosis. Therefore,

maintenance of normal or slightly low systemic vascular resistance is

desirable. Management must be individualized. Inotropes, vasodilators, and

vaso-pressors are administered to achieve optimal hemodynam-ics. LVADs

generally function well as long as there is sufficient intravascular volume to

fill the pump.

Depth of anesthesia is judged, in part, by

hemodynamic parameters. However, LVAD-supported patients may not manifest

increased pulse rates, a classic sign of light anesthe-sia. As previously

discussed, LVADs eject as soon as the blood chamber fills, and it is this rate of

ejection which constitutes the LVAD-supported patient’s pulse rate. Therefore,

the pulse rate is rarely the same as the ECG-derived heart rate. For this

reason, intraoperative tachycardia, as measured by the pulse rate, is

reflective only of the speed of LVAD filling, and not of light anesthesia.

However, while relative hyper-tension is reflective of relative volume overload

and higher pump outputs, it could also reflect heightened adrenergic activity

with increased SVR (Table 11.4). Nevertheless, lack of an acutely increased

blood pressure with surgical stimula-tion is not always a reliable indicator of

adequate depth of anesthesia in an LVAD-supported patient.

Related Topics