Chapter: Modern Pharmacology with Clinical Applications: Antiviral Drugs

Viral Infection and Disease

VIRAL INFECTION

AND DISEASE

Viruses are obligate

intracellular parasites that use many of the host cell’s biochemical mechanisms

and products to sustain their viability. A mature virus (virion) can exist

outside a host cell and still retain its infective properties. However, to reproduce, the virus must enter the host cell, take over the host

cell’s mecha-nisms for nucleic acid and protein synthesis, and direct the host

cell to make new viral particles.

Classification of Viruses

Viruses are composed of one

or more strands of a nu-cleic acid (core) enclosed by a protein coat (capsid).

Many viruses possess an outer envelope of protein or lipoprotein. Viral cores

can contain either DNA or RNA; thus, viruses may be classified as DNA viruses

or RNA viruses. Further classification is usually based on morphology, cellular

site of viral multiplication, or other characteristics.

Examples of DNA viruses and

the diseases that they produce include adenoviruses (colds, conjunctivitis);

hepadnaviruses (hepatitis B); herpesviruses (cytomega-lovirus, chickenpox,

shingles); papillomaviruses (warts); and poxviruses (smallpox). Pathogenic RNA

viruses in-clude arborviruses (tick-borne encephalitis, yellow fever);

arenaviruses (Lassa fever, meningitis); or-thomyxoviruses (influenza);

paramyxoviruses (measles, mumps); picornaviruses (polio, meningitis, colds);

rhab-doviruses (rabies); rubella virus (German measles); and retroviruses

(AIDS).

Viral Replication

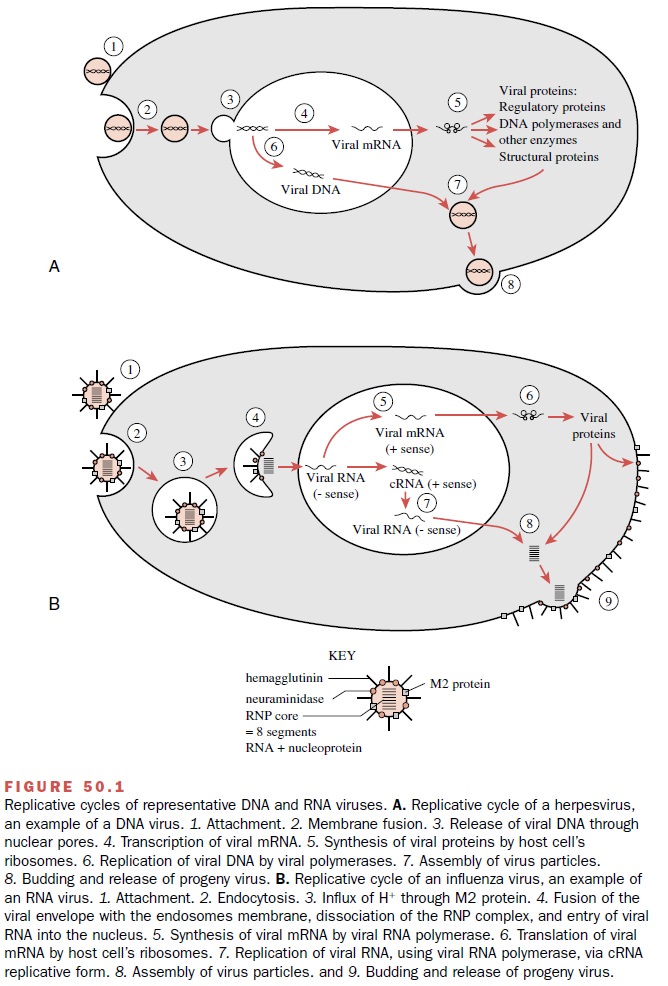

Although the specific details

of replication vary among types of viruses, the overall process can be

described as consisting of five phases: (1) attachment and penetra-tion, (2)

uncoating, (3) synthesis of viral components, (4) assembly of virus particles,

and (5) release of the virus. An overview of the viral replication cycle is

shown in Figure 50.1.

Infection begins when specific receptor sites on the virus recognize corresponding surface proteins on the host cell. The virus penetrates the host membrane by a mechanism resembling endocytosis and is encapsulated by the host cell’s cytoplasm, forming a vacuole. Next, the protein coat dissociates and releases the viral genome, usually into the host cell’s nucleus.

Following the release of its

genome, the virus synthesizes nucleic acids and proteins in sequence. In DNA

viruses, the first genes to be transcribed are the im-mediate–early genes.

These genes code for regulatory proteins that in turn initiate the

transcription of the early genes responsible for viral genome replication.

After the viral DNA is replicated, the late genes are transcribed and

translated, producing proteins required for the assembly of the new virions.

RNA viruses have several major strate-gies for genome replication and protein

expression. Certain RNA viruses contain enzymes that synthesize messenger RNA

(mRNA) using their RNA as a template; others use their own RNA as mRNA. The

retroviruses use viral reverse transcriptase enzymes to produce DNA using viral

RNA as a template. The newly synthesized DNA integrates into the host genome

and is transcribed into mRNA and genomic RNA for progeny virions.

Following their production,

the viral components are assembled to form a mature virus particle. The viral

genome is encapsulated by viral protein; in some cases (e.g. adenovirus,

poliovirus), it is not encapsulated. In certain viruses, such as the

poxviruses, multiple mem-branes surround the capsid. Release of the virus from

the host cell may be rapid and produce cell lysis and death. A slower process

resembling budding may allow the host cell to survive.

Overview of Antiviral Therapy

Three basic approaches are

used to control viral dis-eases: vaccination, antiviral chemotherapy, and

stimula-tion of host resistance mechanisms.Vaccination has been used

successfully to prevent measles, rubella, mumps, poliomyelitis, yellow fever,

smallpox, chickenpox, and hepatitis B. Unfortunately, the usefulness of

vaccines ap-pears to be limited when many stereotypes are involved (e.g.,

rhinoviruses, HIV). Furthermore, vaccines have lit-tle or no use once the

infection has been established be-cause they cannot prevent the spread of

active infections within the host. Passive immunization with human im-mune

globulin, equine antiserum, or antiserum from vaccinated humans can be used to

assist the body’s own defense mechanisms. Intramuscular preparations of im-mune

globulin may be used to prevent infection follow-ing viral exposure and as

replacement therapy in indi-viduals with antibody deficiencies. Peak plasma

concentrations of intramuscular immune globulins occur in about 2 days. In contrast,

intravenously administered immune globulin provides immediate passive immunity.

The chemotherapy of viral

infections may involve interference with any or all of the steps in the viral

replication cycle. Because viral

replication and host cell processes

are so intimately linked, the main problem in

the chemotherapy of viruses is finding a drug that is se-lectively

toxic to the virus. Stimulation of host resistance

is the least used of the antiviral intervention strategies.

Related Topics