Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Pelvic Support Defects, Urinary Incontinence, and Urinary Tract Infection

Urinary Tract Infections

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

An

estimated 11% of U.S. women report at least one physician-diagnosed urinary tract infection (UTI) per year,

and the lifetime probability that a woman will have a UTI is 60%. Most UTIs

in women ascend from bacterial contamination of the urethra. Except in patients

with tuberculosis or in immunosuppressed patients, infections are rarely

acquired by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. The relatively short female

urethra, exposure of the meatus to vestibular and rec-tal pathogens, and sexual

activity that may induce trauma or introduce other organisms, all increase the

potential for infection (Box 28.1). Estrogen

deficiency also causes a decreasein urethral resistance to infection, which

contributes to ascending contamination. This increased susceptibility may

explain the20% prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in women over the age of

65.

Of first

infections, 90% are caused by Escherichia coli.The

remaining 10% to 20% of UTIs are caused by other microorganisms, occasionally

colonizing the vagina and periurethral area. Staphylococcus saprophyticus frequently causes lower UTIs. Proteus, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, and

Box 28.1

Risk Factors for Urinary Tract Infection

Premenopausal Women

History

of urinary tract infection

Frequent

or recent sexual activity

Diaphragm

contraception use

Use

of spermicidal agents

Increasing

parity

Diabetes

mellitus

Obesity

Sickle

cell trait

Anatomic

congenital abnormalities

Urinary

tract calculi

Neurologic

disorders or medical conditions requiring indwelling or repetitive bladder

catheterization

Postmenopausal Women

Vaginal

atrophy

Incomplete

bladder emptying

Poor

perineal hygiene

Rectocele,

cystocele, urethrocele, or uterovaginal prolapse

Lifetime

history of urinary tract infection

Type

1 diabetes mellitus

(From

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Treatment of urinary tract

infections in nonpregnant women. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 91. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 111(3): 785–794.)

Enterobacter

species all have been isolated in women

withcystitis or pyelonephritis, and these frequently are associ-ated with

structural abnormalities of the urinary tract, indwelling catheters, and renal

calculi. Enterococcus species also

have been isolated in women with structural abnormal-ities. Gram-positive

isolates, including group B streptococci, are increasingly isolated along with

fungal infections in women with indwelling catheters.

Clinical History

Patients with lower UTIs typically present with

symptoms of frequency, urgency, nocturia, or dysuria. The symp-toms found vary

somewhat with the site of the infection. Symptoms caused by irritation of the

bladder or trigone include urgency, frequency, and nocturia. Irritation of the

urethra leads to frequency and dysuria. Some patients may report suprapubic

tenderness or urethral or bladder-base tenderness. Fever is uncommon in women

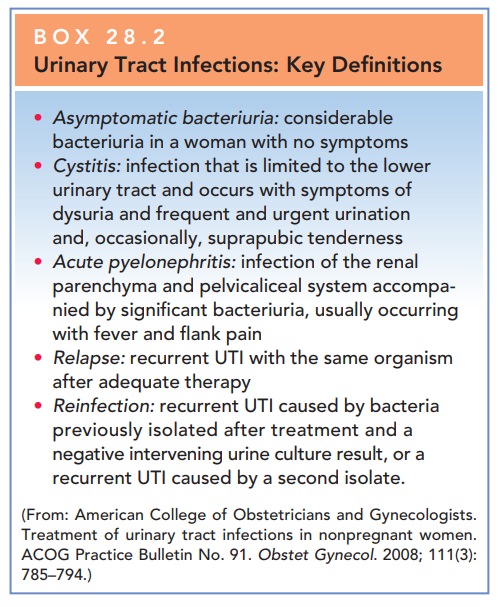

with uncompli-cated lower UTI. Upper UTI

or acute pyelonephritis fre-quently occurs with a combination of fever and

chills, flank pain, and varying degrees of dysuria, urgency, and frequency (Box

28.2).

Laboratory Evaluation

The evaluation of the patient suspected of having a uri-nary tract infection should include a urinalysis.

Box 28.2

Urinary Tract Infections: Key Definitions

Asymptomatic bacteriuria: considerablebacteriuria in a woman with no

symptoms

Cystitis: infection that is limited to the lowerurinary

tract and occurs with symptoms of dysuria and frequent and urgent urination

and, occasionally, suprapubic tenderness

Acute pyelonephritis: infection of the renalparenchyma and

pelvicaliceal system accompa-nied by significant bacteriuria, usually occurring

with fever and flank pain

Relapse: recurrent UTI with the same organismafter

adequate therapy

Reinfection: recurrent UTI caused by bacteriapreviously

isolated after treatment and a negative intervening urine culture result, or a

recurrent UTI caused by a second isolate.

(From:

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Treatment of urinary tract

infections in nonpregnant women. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 91. Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 111(3): 785–794.)

The

initial treatment of a symptomatic lower UTI with pyuria or bacteriuria does

not require a urine culture.

However, if clinical improvement

does not occur within 48 hours or, in the case of recurrence, a urine culture

is useful to help tailor treatment.

A urine

culture should be performed in all cases of upper UTIs.

Urine for these studies is

obtained through a “clean-catch midstream” sample, which involves cleansing the

vulva and catching a portion of urine passed during the middle of uninterrupted

voiding. Urine obtained from catheters or suprapubic aspiration may also be

used. A standard uri-nalysis will detect pyuria, defined as 10 leukocytes per

milliliter, but pyuria alone is not a reliable predictor of infection. However,

pyuria and bacteriuria together on microscopic examination results markedly

increase the probability of UTI.

“Dipstick” tests for infection

based on the detection of leukocyte esterase are useful as screening tests.

However, women with negative test results and symptoms should have a urine

culture or urinalysis or both performed, because false-negative results are

common.

Cultures of urine samples that

show colony counts of more than 100,000 for a single organism generally

indi-cate infection. Colony counts as low as 10,000 for E. coli are associated with infection when symptoms are present. If

a culture report indicates multiple organisms, contami-nation of the specimen

should be suspected.

Treatment

Once infection is confirmed by

urinalysis or culture, antibiotic therapy should be instituted.

Recent

data have shown that 3 days of therapy is equivalent in efficacy to longer

durations of therapy, with eradication rates exceeding 90%.

Recommended agents for the 3-day

therapy include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, ciproflox-acin,

levofloxacin, and gatifloxacin.

In cases of acute pyelonephritis,

treatment should be initiated immediately. The choice of drug should be based

on knowledge of resistance in the community. Once the urine and susceptibility

culture results are available, therapy is altered as needed. Most women can be treated on an out-patient

basis initially or given intravenous fluids and one par-enteral dose of an

antibiotic before being discharged and given a regimen of oral therapy. Patients

who are severely ill, have complications, are unable to tolerate oral

medications or fluids, or who the clinician suspects will be noncompliant with

outpatient therapy should be hospitalized and receive empiric broad-spectrum

parenteral antibiotics.

Women with frequent recurrences

and prior confir-mation by diagnostic tests and who are aware of their symptoms

may be empirically treated without recurrent testing for pyuria. Management of recurrent UTIs should

startwith a search for known risk factors associated with recurrence. These

include frequent intercourse, long-term spermicide use, diaphragm use, a new

sexual partner, young age at first UTI, and a maternal history of UTI.

Behavioral changes, such as using a different form of contraception instead of

spermicide, should be advised. The first-line intervention for the prevention

of the recurrence of cystitis is prophylac-tic or intermittent antimicrobial therapy.

For women with frequent recurrences, continuous prophylaxis with once-daily

treatment with nitrofurantoin, norfloxacin, ciproflo-xacin, trimethoprim,

trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, or another agent has been shown to decrease the

risk of recur-rence by 95%. Drinking cranberry juice has been shown to decrease

symptomatic UTIs, but the length of therapy and the concentration required to

prevent recurrence long-term are not known.

Recurrence

is most common in postmenopausal women; the hypoestrogenic state with

associated genitourinary atrophy likely contributes to the increased

prevalence. Oral and vaginal exoge-nous estrogens have been

studied with varying results.

Screening

for and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is not recommended in nonpregnant,

premenopausal women. Specific groups for whom

treatment of asymptomatic bac-teriuria is recommended include all pregnant

women, women undergoing a urologic procedure in which mucosal bleeding is

anticipated, and women in whom catheter-acquired bacteriuria persists 48 hours

after catheter removal. Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in women with

diabetes mellitus, older institutionalized patients, older patients living in a

community setting, patients with spinal cord injuries, or patients with indwelling

catheters is not recommended.

Related Topics