Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Pelvic Support Defects, Urinary Incontinence, and Urinary Tract Infection

Urinary Incontinence

URINARY INCONTINENCE

The prevalence of urinary

incontinence appears to increase gradually during young adult life, has a broad

peak around middle age, and then steadily increases in the elderly. Urinary

incontinence has been shown to affect women’s social, clinical, and psychologic

well-being. It is esti-mated that less than one half of all incontinent women

seek medical care, even though the condition can often be treated.

Types

Several types of urinary

incontinence have been identified, and a patient may have more than one type

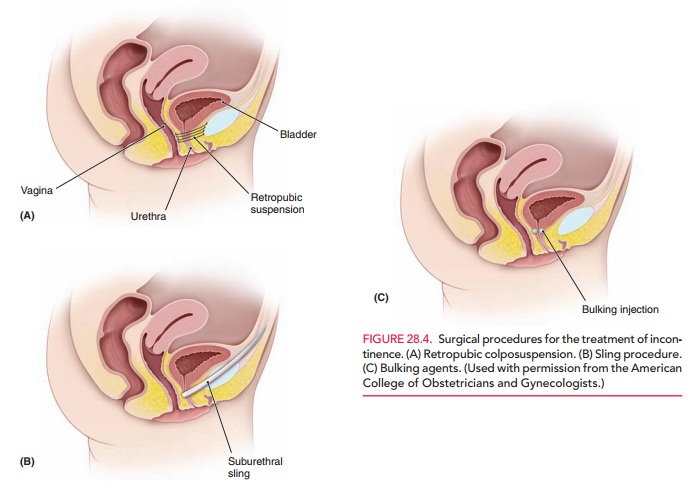

(Table 28.1).

DETRUSOR OVERACTIVITY (URGE INCONTINENCE)

The normal voiding “reflex” is

initiated when stretch receptors within the detrusor muscle, the layer of mus-cle that lines the interior

bladder wall, send a signal to the brain. The brain then decides if it is

socially acceptable to void. The detrusor muscle contracts, elevating the

blad-der pressure to exceed the urethral pressure. The external urethral

sphincter, under voluntary control, relaxes, and voiding is completed.

Normally, the detrusor muscle

allows the bladder to fill in a low-resistance setting. The volume increases

within the bladder, but the pressure within the bladder remains low. Patients

with an overactive detrusor muscle have uninhibited detrusor contractions.

These contractions cause a rise in the bladder pressure that overrides the ure-thral

pressure, and the patient will leak urine without evi-dence of increased

intra-abdominal pressure. Idiopathic detrusor overactivity has no organic

cause, but has a neuro-genic component.

A patient with detrusor overactivity presents with the feel-ing that she must run to the bathroom frequently and urgently. This may or may not be associated with nocturia. These symptoms may occur after bladder surgery to correct stress incontinence or after extensive bladder dissection during pelvic surgery.

STRESS URINARY INCONTINENCE

Normal physiology and anatomy

allow for increased abdominal pressure to be transmitted along the entire

urethra. In addition, the endopelvic fascia that extends beneath the urethra

allows for the urethra to be com-pressed against the endopelvic fascia, thus

maintaining a closed system and maintaining the bladder neck in a stable

position. In patients with stress incontinence, increased intra-abdominal

pressure is transmitted to the bladder, but not to the urethra (specifically,

the urethral–vesical junction [UVJ]), due to loss of integrity of the

endopelvic fascia. The bladder neck descends, the bladder pressure is elevated

above the intra-urethral pressure, and urine is lost. Patientswith stress incontinence present with loss of urine during

activities that cause increased intra-abdominal pressure, such as coughing,

laughing, or sneezing.

MIXED INCONTINENCE

Some

patients may have symptoms of both urge incontinence and stress incontinence. These

patients experience urine leakageduring coughing, laughing, or sneezing; the

increased intra-abdominal pressure that occurs during these activi-ties causes

the UVJ to descend and also stimulates the detrusor to contract. This clinical

scenario may be treated as stress or as detrusor instability, although it is

not clear which approach offers a better outcome.

OVERFLOW INCONTINENCE

In this form of incontinence, the

bladder does not empty completely during voiding due to an inability of the detru-sor

muscle to contract. This may occur because of an obstruction of the urethra or

a neurologic deficit that causes the patient to lose the ability to perceive

the need to void. Urine leaks out of the bladder when the bladder pressure

exceeds the urethral pressure. These

patients expe-rience continuous leakage of small amounts of urine.

Evaluation

Patients with urinary

incontinence should undergo a basic evaluation that includes a history,

physical examination, direct observation of urine loss, measurement of postvoid

residual volume, urine culture, and urinalysis. These tests and examinations

are performed to rule out urinary tract infection, neuromuscular disorders, and

pelvic support defects, all of which are associated with urinary inconti-nence.

The patient should also be asked about her fluid intake, the relationship of

her symptoms to fluid intake and activity, and medications. A voiding diary may

be helpful in this evaluation process.

Urodynamic testing may also be

useful. These tests measure the pressure and volume of the bladder as it fills

and the flow rate as it empties. In single-channel

uro-dynamic testing, the patient voids, and the volume isrecorded. A

urinary catheter is then placed and the postvoid residual (PVR) urine is

recorded. The bladder is filled in a retrograde fashion. The patient is asked

to note the first sensation that her bladder is being filled. She then is asked

to note when she has a desire to void, and when she can no longer hold her

urine. Normal values are: 100–150 cc for first sensation, 250 cc for first

desire to void, and 500–600 cc for maximum capacity. In multichannel urodynamictesting, a transducer is placed in the

vagina or rectum tomeasure intra-abdominal pressure. A transducer is placed in

the bladder, and EMG pads are placed along the per-ineum. This form of testing

provides an assessment of the entire pelvic floor, and an uninhibited bladder

contraction can be clearly documented.

Cystourethroscopy

may be used in the evaluation ofurinary

incontinence. In this procedure, a slender, lighted scope is introduced into

the bladder. Cystourethroscopy can help to identify bladder lesions and foreign

bodies, as well as urethral diverticula, fistulas, urethral strictures, and

intrinsic sphincter deficiency. It frequently is used as part of the surgical

procedures to treat incontinence.

Treatment

There are many options for

treatment. Often, treatments are more effective when used in combination.

NONSURGICAL TREATMENT OPTIONS

Lifestyle interventions that may

help modify incontinence include weight loss, caffeine reduction and fluid

manage-ment, reduction of physical forces (e.g., work, exercise), ces-sation of

smoking, and relief of constipation. Pelvic muscle training (Kegel exercises)

can be extremely effective in treat-ing some forms of incontinence, especially

stress inconti-nence. The exercises work to strengthen the pelvic floor and

thus decrease the degree of urethral hypermobility. The patient is instructed

to repeatedly tighten her pelvic floor muscles as though she were voluntarily

stopping a urine stream. Biofeedback techniques and weighted vaginal cones are

available to assist patients in learning the proper tech-nique. When performed correctly, these exercises

have success ratesof about 85%. Success is defined as a decreased number

ofepisodes of incontinence. However, once the patient stops the exercise

regimen, she will revert to her original status. Other treatments for stress

incontinence include various pessaries and continence tampons that can be

placed vagi-nally to aid in urethral compression.

Behavioral training is aimed at

increasing the patient’s bladder control and capacity by gradually increasing

the amount of time between voids. This type of training is most often used to

treat urge incontinence, but may also be successful in treating stress

incontinence and mixed incontinence. It may be augmented by biofeedback.

A number

of other pharmacologic agents appear to be effective for treating frequency,

urgency, and urge incontinence. However, the response to

treatment often is unpredictable, and side effects are common with effective

doses. Generally, drugs improve detrusor overactivity by inhibiting the

con-tractile activity of the bladder. These agents can be broadly classified

into anticholinergic agents, tricyclic antidepres-sants, musculotropic drugs,

and a variety of less commonly used drugs

Surgical Therapy

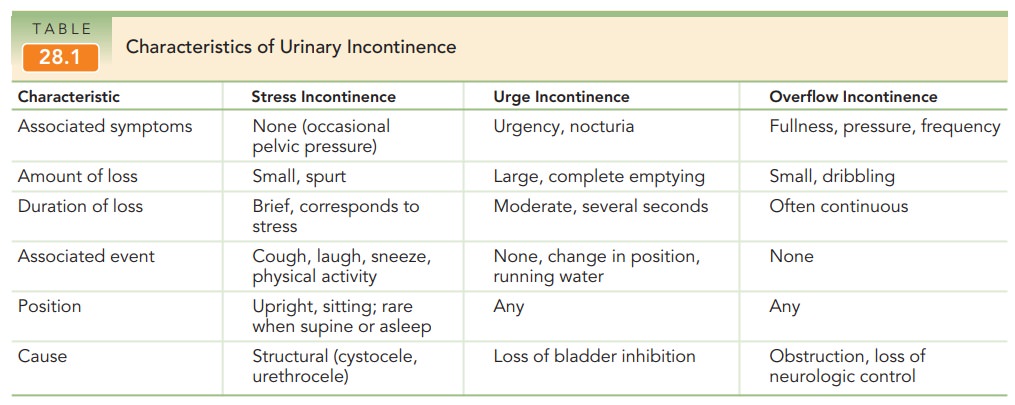

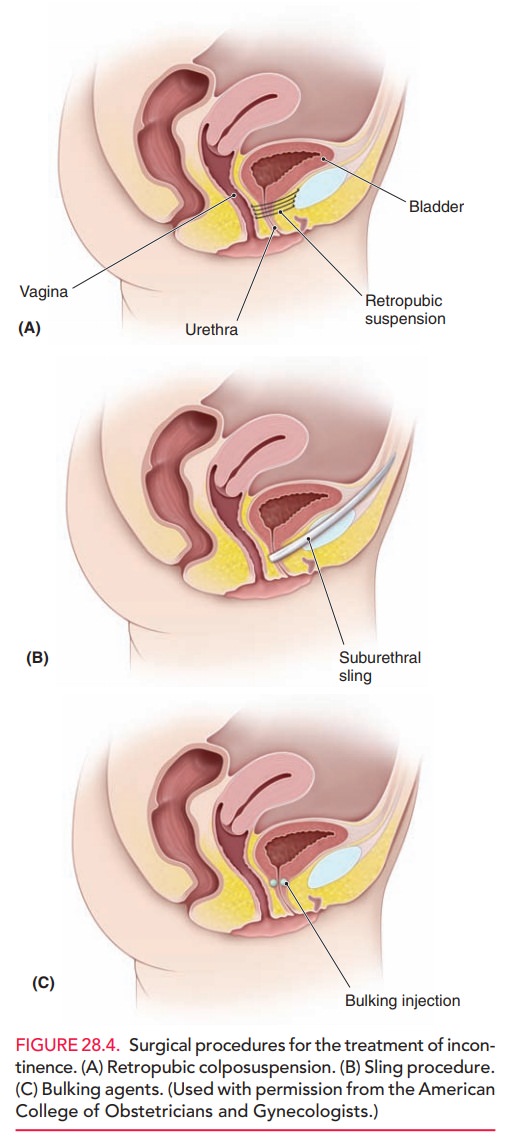

Many surgical treatments have

been developed for stress urinary incontinence, but only a few—retropubic colpo-suspension and sling procedures—have survived

andevolved with enough supporting evidence to make recom-mendations (Figs. 28.4

A and B). The aim of retropubic colposuspension is to suspend and stabilize the

anterior vaginal wall and, thus, the bladder neck and proximal urethra, in a

retropubic position. This prevents their descent and allows for urethral

compression against a sta-ble suburethral layer. In the Burch procedure, which can be performed abdominally or

laparoscopically, two or three nonabsorbable sutures are placed on each side of

the mid-urethra and bladder neck. Another procedure uses tension-free tape

placed at the midurethra to raise the urethra back into place. This procedure

can be done through the vagina. The success of tension-free vaginal tape has

led to the introduction of similar products with modified methods of

midurethral sling placement (retropubic “top-down” and transobturator). Bulking agents, such as collagen,

carbon-coated beads, and fat, are used for the treatment of urody-namic stress

incontinence with intrinsic sphincter deficiency (Fig. 28.4C). They are

injected transurethrally or peri-urethrally in the periurethral tissue around

the bladder neck and proximal urethra. They provide a “washer” effect around

the proximal urethra and the bladder neck. These agents usually are used as

second-line therapy after surgery has failed, when stress incontinence persists

with a non-mobile bladder neck, or among older, debilitated women for whom any

form of operative treatment may be hazardous.

Success rates vary depending on the skill of the surgeon and the technique used. Tension-free vaginal tape and the Burch suspension have success rate at five years of 85%. Preoperative counseling should include not only the risks of the pro-cedures, but also the goals. The patient must understand thatthe procedure may not allow her to be completely continent, as overcorrection (making the sling too tight) may lead to urinary retention. In addition, studies only show 5-year data; thus, surgery should not be presented as a permanent solu-tion. One study of women who underwent Burch colposuspensionfound that the cure rate of stress incontinence gradually decreased over 10–12 years, reaching a plateau at 69%. Approximately10% of patients required at least one additional surgery to cure their stress incontinence.

Related Topics