Chapter: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Pelvic Support Defects, Urinary Incontinence, and Urinary Tract Infection

Pelvic Support Defects

PELVIC SUPPORT DEFECTS

Pelvic

support defects comprise a variety of conditionsrelated to loss of

connective tissue support surrounding the reproductive tract organs, including

loss of uterine support, paravaginal tissue support, bladder wall and

urethrovesical angle support, and support overlying the distal rectum. Pelvic organ prolapse is a disorder in

which organshave lost their support and descend through the urogen-ital hiatus.

Patients with pelvic support disorders

present inmany different and often subtle ways. To identify patientswho

would benefit from therapy, the physician should be familiar with the types of

pelvic support defects and the approach to the patient with symptoms suggestive

of these problems.

Although

not exclusively a condition of advancing age, pelvic support defects are more

common among women of this group, as tissues become less resilient and

accumulated stresses have an additive effect. Possible

risk factors include genetic pre-disposition, parity (particularly vaginal

birth), menopause, advancing age, prior pelvic surgery, connective tissue

dis-orders, and factors associated with elevated intra-abdominal pressure

(e.g., obesity, chronic constipation with excessive straining). Loss of pelvic

support can have both medical and social implications that necessitate evaluation

and intervention. Signs and symptoms of these disorders include urinary or

fecal loss or retention; vaginal pressure or heaviness; abdominal, low back,

vaginal, or perineal pain or discomfort; a mass sensation; difficulty walking,

lift-ing, or sitting; cervical hypertrophy, excoriation, ulcera-tion, or

bleeding; difficulty with sexual relations; and stress or fear related to

anxiety about the problem. Life-threatening symptoms, such as ureteral

obstruction, systemic infection, incarceration, and evisceration, are uncommon.

Most women who are identified as having

apelvic support defect on physical examination are not clinically affected, and

physical findings are not well-correlated with specific pelvic symptoms.

Causes

The pelvic organs are supported

by a complex interaction of muscles (levator muscles), fasciae (urogenital

diaphragm, endopelvic fascia), and ligaments (uterosacral and cardinal

ligaments). Each of these structures can lose its ability to provide support

through birth trauma; chronic elevations of intra-abdominal pressure, e.g., in

obesity, chronic cough, or repetitive heavy lifting; intrinsic weaknesses; or

atrophic changes caused by aging or estrogen loss. For many years, pelvic

support disorders were believed to result solely from attenuation or stretching

of pelvic connective tissue.

Recently,

investigators have shown that breaks or tears of site-specific connective

tissue result in identifiable anatomic defects in the connective tissue

network.

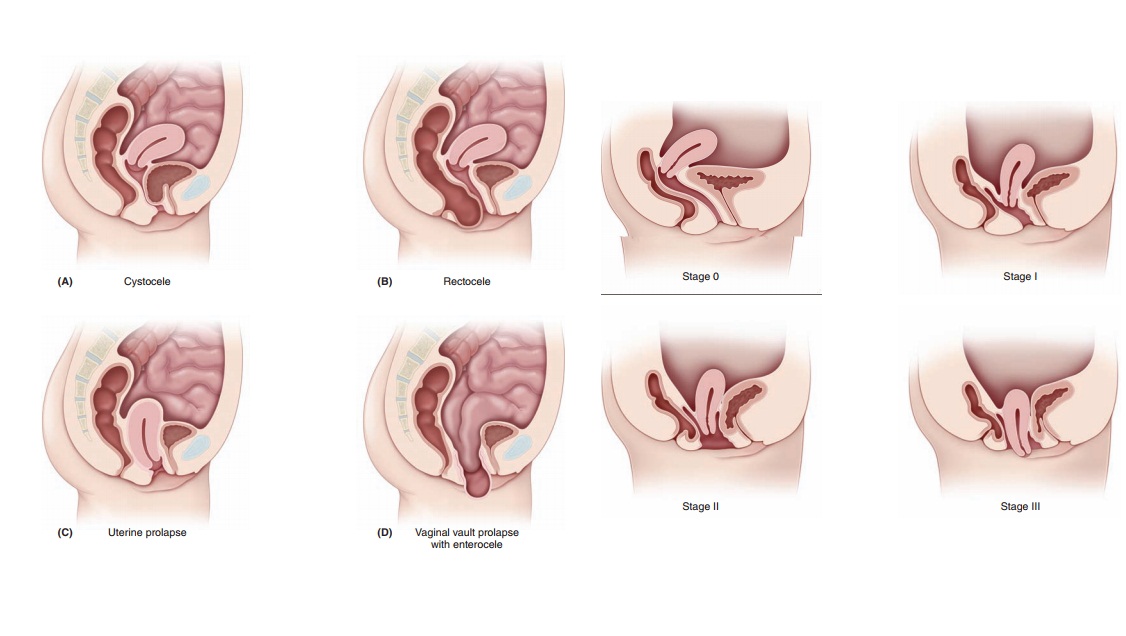

Types

Loss of adequate support for the

pelvic organs may be man-ifest by descent or prolapse of the uterus, urethra

(urethral detachment or urethrocele),

bladder (cystocele), or rectum (rectocele). A true hernia at the top of

the vagina allowing the small bowel to herniate through (enterocele) can also occur. These anatomic defects are illustrated

in Figure 28.1.

A useful concept that can help in understanding these disorders is to visualize the anterior vaginal wall as a ham-mock. With good support, the hammock is pulled tight, allowing the bladder to rest on the hammock. When sup-port is lost, the hammock sinks, as if someone were now sitting in the hammock. The bladder now forces the ante-rior vaginal wall down and out, creating an anterior wall defect or cystocele. A similar force occurs in creating a rectocele, a posterior wall defect. The posterior vaginal wall loses the lateral support, and thus the pressure from the rectum forces the posterior vaginal wall in an upward direction.

Loss of support for

the uterus can lead to vary-ing degrees of uterine prolapse. When the cervix

descends beyond the vulva, it is termed procidentia.

Loss of tissue support can also result in prolapse of the vaginal vault in

patients who have had a hysterectomy. Although

loss of sup-port may affect any of the pelvic organs individually, multiple

organ involvement is most common.

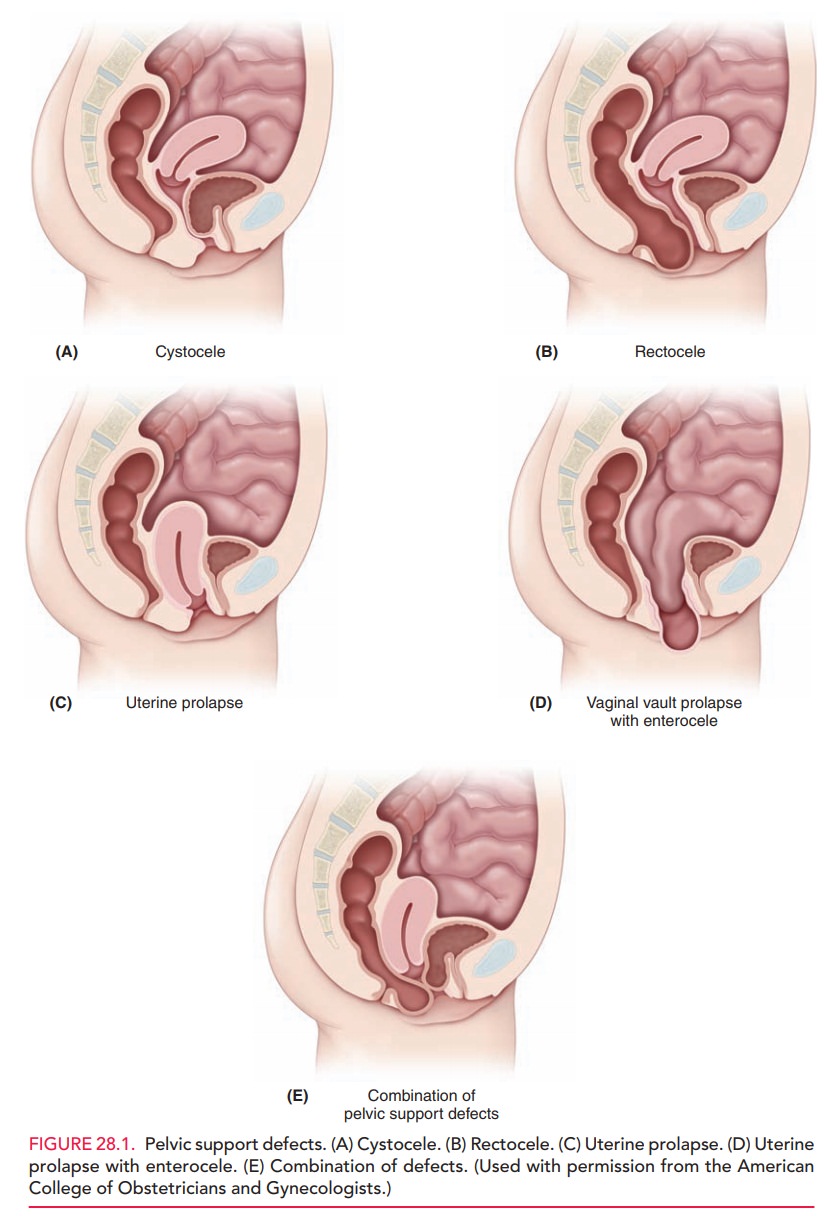

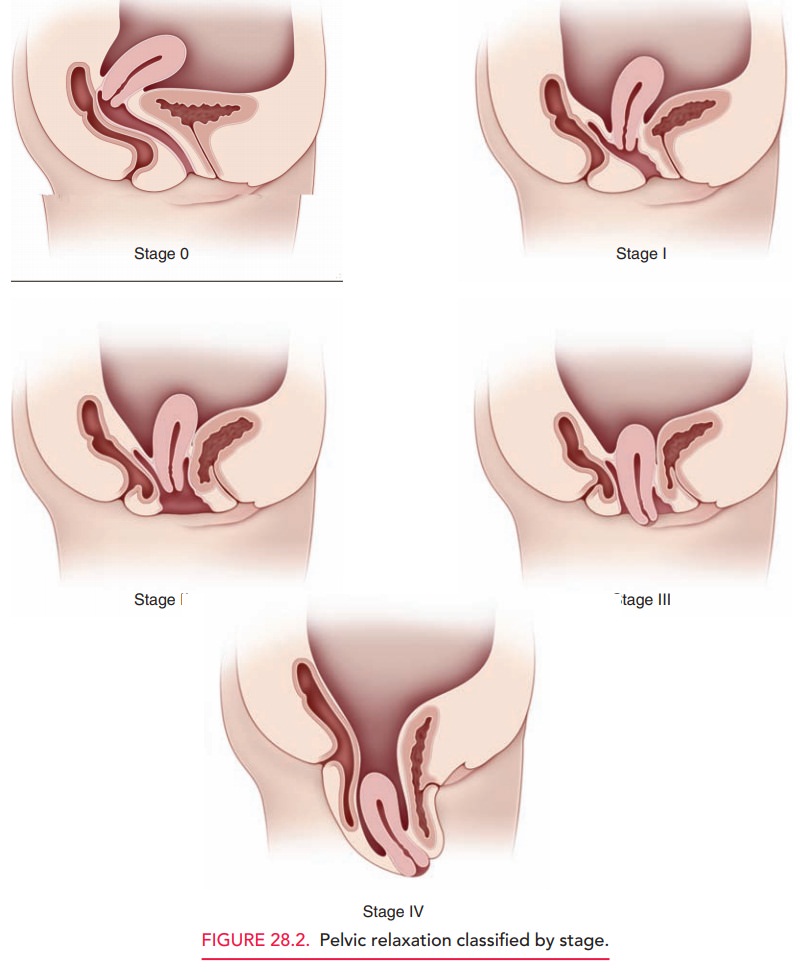

Evaluation

The evaluation of patients with

pelvic relaxation is based on the history and physical examination. A comprehensive phys-ical examination

includes the evaluation of specific sites and mea-surements that aid in

classifying the severity of prolapse and allows for planning of treatment

options. Specific sites to be evaluatedinclude the urethra, vagina

(including the anterior and pos-terior vaginal walls, paravaginal wall, and

vaginal apex), perineum, and anal sphincter. A common classification scheme

used to describe pelvic support defects involves the use of specific

measurements that are recorded during the physical examination that have been

quantified into stages (Fig. 28.2):

·

Stage 0: No prolapse. The cervix

(or vaginal cuff, if the patient has had a hysterectomy) is at least as high as

the vaginal length.

·

Stage I: The leading part of the

prolapse is more than 1 cm above the hymen.

·

Stage II: The leading edge is

less than or equal to 1 cm above or below the hymen.

·

Stage III: The leading edge is

more than 1 cm beyond the hymen, but less than or equal to the total vaginal

length.

·

Stage IV: Complete eversion.

A common complaint of patients

with a cystocele or ure-throcele is urinary incontinence. As the bladder loses

its support, the mobility of the urethra increases, and it pulls away from the

pubic symphysis when the patient performs the Valsalva maneuver. Incontinence does not occur in allpatients,

and the degree of incontinence is often not commensurate with the degree of

pelvic relaxation. The extent of urethralhypermobility is assessed by the Q-tip test. With the patient in the

lithotomy position, a cotton-tipped swab lubricated with lidocaine jelly is

placed into the bladder and pulled back until resistance is met. Once placed,

the patient is asked to bear down. If there is urethral hypermobility, the

urethral-vesicular junction (UVJ) deflects downward, thus causing the swab to

rise. An angle greater than 30 degrees is considered a positive test. The Q-tip

test does not predict incontinence, but provides more detail to the physical

examination. It may also be used to predict the success of treatment options

that work by stabilizing the urethra.

Some patients with Stage III or

IV prolapse may not present with incontinence, but have experienced it in the

past. These patients may have a kinked urethra that prevents complete

urination. The medical issue of great-est concern for a patient with

significant prolapse is hydronephrosis or hydroureter, although this condition

is uncommon. The insertion of the ureter into the trigone kinks the trigone,

and urine begins to back up into the col-lecting system. A renal ultrasound is

helpful to evaluate this scenario.

Most pelvic relaxation disorders

are the result of structural failure of the tissues involved, but other

con-tributing factors should be considered in the complete care of the patient.

Questions that should be asked include the following:

· Has there

been a change in intra-abdominal pressure? If yes, what is the cause?

· Does the

patient have a chronic cough that has precip-itated her symptoms?

· Is a

neurologic process (such as diabetic neuropathy) complicating the patient’s

presenting complaint?

Each of these issues should be

considered prior to the selection of a diagnostic or therapeutic plan.

Differential Diagnosis

The presumptive diagnosis of a

pelvic support defect is based on the evaluation of the structural integrity of

pelvic support by physical examination. Other processes that may be considered

include urinary tract infection, which may lead to urgency and urethral

diverticulum or Skene gland abscesses, which may mimic a cystourethrocele and,

in the case of diverticula, may be a source of incontinence. These conditions

can be identified by the patient’s symp-toms, careful “milking” of the urethra,

or cystoscopy. It is occasionally difficult to differentiate between a high

rec-tocele and an enterocele. This distinction may be facili-tated through

rectal examination or the identification of the small bowel in the hernia sac.

It is common for the diagnosis of an enterocele not to be established until

sur-gical repair is undertaken.

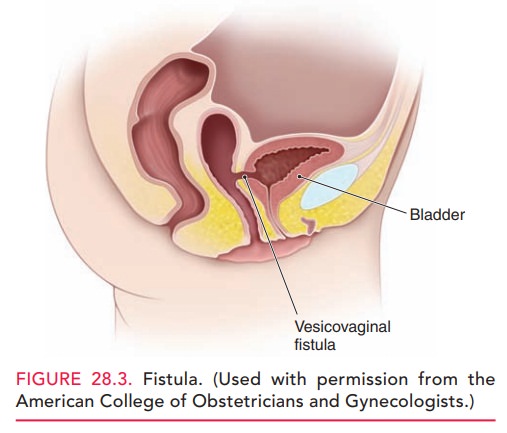

In patients who have had a

history of recent pelvic surgery or radiation, fistulae between the vagina and

the bladder (vesicovaginal), urethra (urethrovaginal), or ureter

(ureterovaginal) should also be considered. Fistulae should also be considered

in patients who present with involun-tary loss of urine. A communication

between the bladder and the uterus (vesicouterine) may also be found on rare

occasions. A fistula also may occur between the rectum and vagina (rectovaginal

fistula), resulting in the passage of flatus or feces from the vagina (Fig.

28.3).

Treatment

Women with prolapse who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic can be observed at regular intervals, unless new, bothersome symptoms develop. The option of non-surgical management should be discussed with all women with prolapse. Nonsurgical alternatives include pessaries, pelvicfloor exercises, and symptom-directed management. A variety of surgical procedures can also be considered.

Pessaries can be used in any situation when a womanprefers a nonsurgical alternative. Pessaries can be fitted in most women with prolapse, regardless of prolapse stage or site of predominant prolapse, and are used by 75% of urogynecologists as first-line therapy for prolapse. Pessary devices are available in various shapes and sizes, and can be categorized as supportive (such as a ring pessary) or space-occupying (such as a donut pessary). Pessaries commonly used for prolapse include ring pessaries (with and without support) and Gellhorn, donut, and cube pessaries.

Surgical treatments for prolapse include hysterectomy, uterosacral or sacrospinous ligament fixation by the vaginal approach, or sacral hysteropexy (abdominal attachment of the lower uterus or upper vagina to the sacral promon-tory with synthetic mesh) by the abdominal approach. Colpocleisis (complete obliteration of the vaginal lumen)can be offered to women who are at high risk for complica-tions with reconstructive procedures and who do not desire vaginal intercourse.

Many women with advanced

prolapse, particularly prolapse involving the anterior vagina, will not have

symp-toms of urinary incontinence. Some of these women will become incontinent

after prolapse surgery.

Clinicians

should discuss with women the potential risks and benefits of performing a

prophylactic anti-incontinence procedure at the time of prolapse repair.

Related Topics