Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Stimulants and Related Compounds

Treatment with Stimulant Medications

Treatment

with Stimulant Medications

An

effective treatment strategy for this chronic disorder of ADHD requires a plan

for follow-up and monitoring. Techniques involve regular follow-up visits, the

use of rating forms from parent and teacher, and the monitoring of academic

progress in the school. Seeing the patient and a family member regularly is

essential, often on a once-monthly basis when the medication prescription must

be renewed.

Preparation of the Patient

Does the child’s attitude about drug treatment influence its success? Concerns that medications may create negative attributions or dysphoric effects in children with ADHD have not as a rule been confirmed in direct tests. Excellent studies show that there is considerable variability in children’s attributions, as well as their mood response to pills. Pelham and colleagues (1992) found a subgroup of “depressogenic” children who gave external credit for positive events and internal blame for negative events. This group was above the median on attributions of success to their pills. Comorbidity and family history for anxiety and/or depression seemingly are relevant variables in prediction of such attributional effects. During treatment, a small percentage of stimulant-treated children do become dysphoric, weepy and mournful. Children who respond with depressogenic attributions or dysphoria may be children whose depressive diathesis is indistinguishable from ADHD and who are therefore mistakenly diagnosed as ADHD and treated with stimulants. Given the overlap of depression and ADHD, and the findings that depressogenic cognitive styles predict later depression, it could be important to identify those children who may be prone to attribute their success to pills rather than to their own effort, even though most patients do not do so.

Physicians

can explain the reasons for taking pills and how the pills can prove helpful in

school and at home. Children often have negative attitudes about treatment,

thinking of treatment as a punishment. Pill taking can be socially stigmatizing

to the child with ADHD if the daily trip to the nurse generates peer ridicule.

Discussing the problem of in-school pill administration may be of great

interest to the child, and he or she should be included in all discussions

about dosing and changing of doses. At best, it may help with compliance.

Consideration of Side Effects

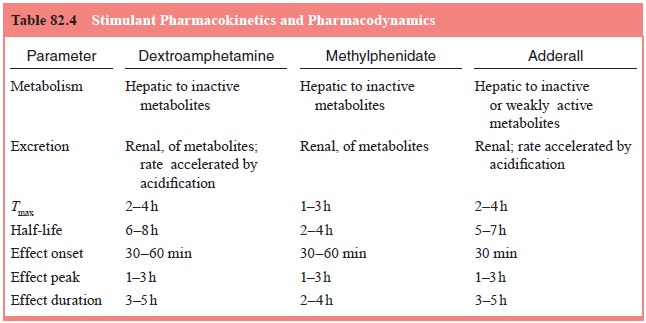

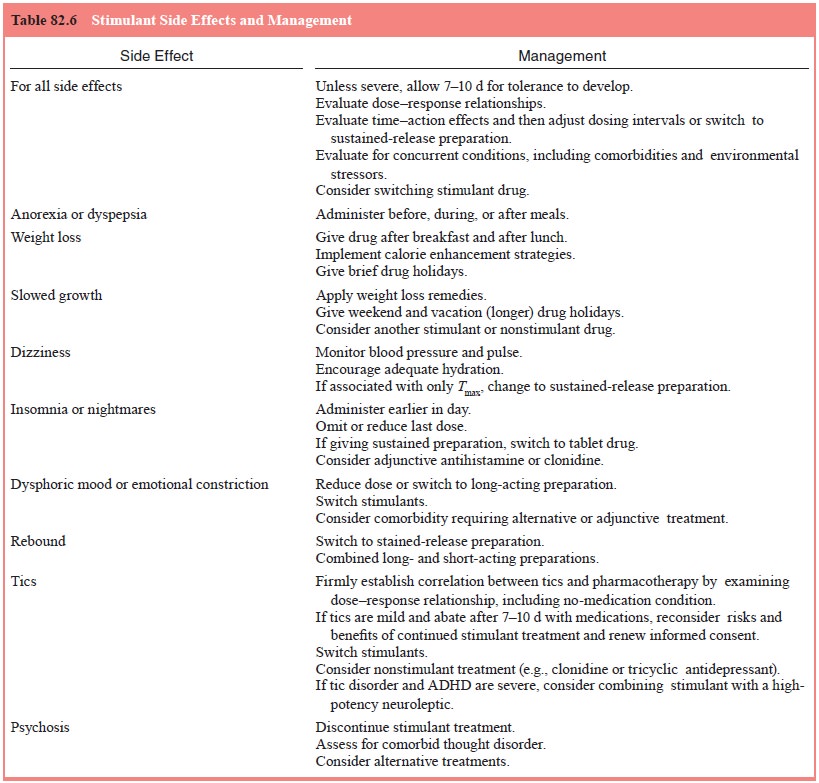

Common

side effects and their management are noted in Table 82.4. Stimulant side

effects are dose dependent and range from mild to moderate in most children.

The management of stimulant-related adverse effects generally involves a

temporary reduction of dose or a change in time of dosing. MPH has an excellent

safety record, probably because the duration of action is so brief.

Rebound One adverse effect, commonly

known as behavioral rebound, appears

when children experience psychostimulant withdrawal at the end of the school

day. Children present with afternoon irritability, overtalkativeness,

noncompliance, excit-ability, motor hyperactivity and insomnia about 5 to 15

hours after the last dose. If rebound occurs, many physicians add a small

afternoon MPH dose or add a small dose of a tricyclic antidepressant.

Seizure Disorders A

commonly held notion is that stimulants lower

the seizure threshold. The PDR warns against the use of stimulants in children

with preexisting seizure disorders. Both ADHD and seizure disorders are quite

prevalent and may occur in the same individual, so the question of the risk of

stimulant treatment may frequently arise. Current practice is to give chil-dren

with ADHD and epilepsy a combination of anticonvulsant and MPH. Plasma levels

of the anticonvulsant should be moni-tored to avoid toxicity resulting from

MPH’s competitive inhibi-tion of metabolic pathways. At the doses used to treat

ADHD in children, the psychostimulants have variable but minimal effects on the

seizure threshold.

Long-term Stimulant Effects: Growth Velocity Reductions

Adults

taking amphetamines routinely experience weight loss, which can be attributed

to reduced appetite and decreased food intake. The drug’s action on the lateral

hypothalamic feeding center may explain this effect. Appetite suppression

differs among different species, with humans showing only mild effects with

rapid onset of tolerance. Children with ADHD taking psy-chostimulants routinely

show appetite suppression when starting treatment. For this reason, dosing

should optimally occur after breakfast and lunch. Even though the daytime

appetite is re-duced, hunger rebounds in the evening. These effects on appetite

often decrease within the first 6 weeks of treatment.

The

growth effects of MPH appear to be minimal. Height and weight should be

measured at 6-month intervals during stim-ulant treatment and recorded on

age-adjusted growth forms to determine the presence of a drug-related reduction

in height or weight velocity. If such a decrement is discovered during

main-tenance therapy with psychostimulants, a reduction in dosage or change to

another class of medication can be carried out.

Continuing Stimulant Treatment in Patients with Tic Disorders

The PDR

suggests that the presence of tics is a contraindication to stimulant usage.

With the comorbidity of ADHD in children with Tourette’s disorder estimated to

fall between 20 and 54%, there is a concern that a stimulant’s dopamine agonist

action will unmask, trigger, accelerate, or provoke irreversible Tourette’s

symptoms. This worry is enhanced by a number of papers, some of them

retrospective, that reported onset of tics after stimulant treatment had begun.

Drug Interactions

(See

Table 82.5 for a listing of common drug interactions.) Mixing psychostimulants

with other psychotropic medications is generally not advisable. Most serious is

the addition of a psy-chostimulant to a monoamine oxidase inhibitor

antidepressant regimen, a potentially lethal combination that can elevate blood

pressure to dangerous levels. Additive effects between psychos-timulants and

the systemic agents used to treat asthma can pro-duce feelings of dizziness,

tachycardia, palpitation, weakness and agitation. Theophylline, for example,

when taken orally (Theo-Dur Sprinkle), can have this undesirable agitating

effect. It is best to ask the pediatrician or allergist to switch from the orally

ingested preparation to an inhalant to avoid such additive sympathomimetic

effects.

Psychostimulants

compete with other medications for the same metabolic pathway and have been

thought to produce an increase in the plasma concentration of both drugs. The

psychostimulants can also interfere with the action of other medications. MPH

can block the antihypertensive action of guanethidine. DEX blocks the action of

some beta-adrenergic antagonists (e.g., propranolol) and slows the intestinal

absorption of phenytoin and phenobarbital. The renal clearance of DEX is

enhanced by urine acidifying agents, so that grapefruit juice will shorten the

elimination half-life of the medication. Conversely, urine alkalinizing agents

decrease clearance. This is also true for ritalinic acid, although this

metabolite is not active in the CNS. MPH may elevate the plasma level of

antidepressants, anticonvulsants, coumarin anticoagulants and phenylbutazone.

MPH may increase the concentration of the serotonin reuptake blocker fluoxetine,

potentially enhancing agitation, although no such side effect was seen in a

single case report of the treatment of an 11-year-old boy with both ADHD and

obsessive–compulsive disorder. Other medications have been combined

successfully with MPH, such as clonazepam to reduce tics. Clonidine has been

added to reduce sleep disturbances associated with ADHD and with stimulant

medication. Bupropion may exacerbate tics when added to MPH given to children

with ADHD.

Initiation of Treatment

Medication

treatment begins with a choice of medication. Although the MPH or DEX

psychostimulant types have equal efficacy, MPH is often used first.

Titration

serves two purposes: acclimatization of the child to the drug and determination

of his or her best dose. School-age children should be started with low doses

to minimize adverse effects. Psychostimulant medication should be taken at or

just after mealtime to lessen the anorectic effects; studies have shown

that food

may enhance drug absorption. MPH treatment can be initiated with a single 5 mg

dose at 8:00 am for 3 days; then a 5 mg dose at 8:00 am and at noon for the

next 3 days; then 10 mg at 8:00 am and 5 mg at noon for 3 days; and finally 10

mg at 8:00 am and 10 mg at noon are given and maintained for at least 2 weeks.

Preschoolers may start as low as 2.5 mg at 8:00 am but build to the same total

20 mg/day dose of MPH. The dosing instructions should be written down for the

parent, with dates and times specified in detail. A photocopy of the instructions

should be kept in the patient’s chart.

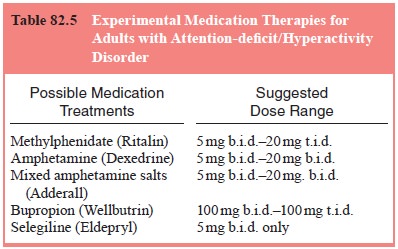

Table

82.6 is an inventory of stimulant drugs and doses. DEX is usually started at

2.5 to 5 mg/day and gradually increased in 2.5- to 5-mg increments; MPH is

usually started at 5 mg b.i.d. and then titrated in increments of 5 mg/dose

every 4 to 7 days. Peak behavioral effects are noted 1 to 3 hours after

ingestion and dissipate in 3 to 6 hours for both MPH and DEX.

The

Conners Teacher Rating Scale is then repeated. Further dose adjustments up or

down depend on the rating scale’s scores, teachers’ verbal reports, parents’

comments, and adverse effects experienced by the child. The minimal effective

total daily dose and optimal timing of medication administration should be de-

termined before switching to the sustained-release 20 mg formulation.

Eventually, one dose of standard MPH may have to be mixed with one

sustained-release 20 mg pill at 8:00 am (to give early- and late-morning

coverage), just as one administers short and long-acting insulin at the same

time.

Monitoring

Maintenance

plans should include schedules for the regular collection of information that

constitutes the child’s therapeutic drug monitoring. Each child’s response to

psychostimulants is different. Likewise, each family’s needs are different.

Plans for medication vacations and weekend and after-school dosing must be

individualized.

Medication

compliance should be monitored at each visit. The parent is instructed to bring

the medication bottle along so that pill counts can be done monthly and

compared with the prescription dates. Height and weight should be taken every 6

months, and the child’s pediatrician can be requested yearly to perform a

complete physical examination and blood work (complete blood count, liver

function studies). The frequency of visits depends on the other therapies

recommended. These may include once-monthly parental counseling, twice-monthly

individual therapy, or weekly meetings for individual psychotherapy or

behavioral modification management. A minimal frequency should be once monthly,

particularly in the nine states requiring multiple-copy prescription forms,

which limit the amount of psychostimulant ordered to a 30-day supply.

The next

component of monitoring is the use of structured

rating scales. These have been the

backbone of psychostimulant treatment

research but also have utility in clinical practice. Each physician should

choose a scale that she or he finds easy to interpret and convenient to use. It

should be available in both parent and teacher formats. These scales, however,

should not be used as substitutes for an open discussion with the teacher.

These

rating forms should be collected every 4 months and whenever the physician

needs to make decisions about dosage adjustment, time of dosing, or even

continuation of medication. Although the original 39-item Conners Teacher

Rating Scale is ubiquitous in the field of child psychopharmacology, Satin and

colleagues (1985) have shown the validity of the shorter, 10-item Abbreviated

Rating Scale both as a repeated measure and as a screening tool for identifying

school-age children with ADHD. This short form is good for tracking children in

maintenance treatment. Like most scales, the Abbreviated Rating Scale assigns

weights to each scale point. With a 10-item scale, and each point weighted

between 0 (“not at all”) and 3 (“very much”), 10 checks by a parent in the

“very much” column yields a total score of 30.

Unlike

the situation with anticonvulsants, it has not proved effective to monitor

psychostimulants by maintaining plasma concentrations within a therapeutic

range. Alternative medications such as desipramine, however, do lend themselves

to regular plasma level monitoring every 3 months.

Phases of Treatment

Medication

therapy can be divided into baseline, titration and maintenance phases. Before

the first pill is given, baseline data on height, weight, blood pressure and

heart rate should be col-lected as well as a complete blood count. The Conners

Teacher Rating Scale and Conners Parent Rating Scale can also be col-lected.

Standardized scoring methods for the teacher rating scale can be used to

generate a hyperactivity factor score.

The

duration of treatment is an important step in the generation of a treatment

plan for a child with ADHD. Although there is no clear-cut recommendation for

the length of psychostimulant treatment, many parents have a reasonable

expectation that it will not be open-ended. The onset of puberty is one

possible stopping point for psychostimulant medication. School-age children

were thought to respond “paradoxically”, calming down on stimulant medication,

an effect that was supposedly lost at puberty. Adolescents with ADHD, who may

be at risk for substance abuse, were thought to be particularly vulnerable to

psychostimulant euphoria and to abuse of their medications. In addition, more

recent prospective follow-up studies suggest that the motor hyperactivity of

ADHD disappears between ages 16 and 23 years.

Integration with Other Modalities:

Multimodal Treatment

Medication

is only one component of a comprehensive therapeu-tic treatment plan. New

standards have been promulgated for the treatment of ADHD recommending

multimodal therapy includ-ing psychological, educational and social components.

This was first reported by Satterfield and colleagues (1980) to be success-ful

in maintaining the short-term stimulant gains for periods of 2 years or more.

Related Topics