Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Stimulants and Related Compounds

Formulation of Treatment

Formulation

of Treatment

What Is Being Treated

There are two main indications for the use of MPH: narcolepsy and ADHD. Other stimulants differ somewhat, with the indica-tions for methamphetamine (Desoxyn Gradumets) including ADHD and obesity.

Diagnosis of the Stimulant-treatable Disorders

Attention-defi cit/Hyperactivity Disorder

ADHD is a

heterogeneous behavioral disorder of unknown etiol-ogy. As its name suggests,

ADHD is characterized by inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity of varying

severity. The disorder, which typically begins in early childhood and lasts

into adult-hood in a substantial minority, if not a majority, of cases,

fre-quently leads to profound social and academic impairments. For a complete

discussion of the ADHD diagnosis, see Chapter 28.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy

is a chronic neurological disorder that presents with excessive daytime

sleepiness and various problems of rapid eye movement physiology, such as

cataplexy (unexpected decreases in muscle tone), sleep paralysis and hypnagogic

hallucinations, which are intense dream-like imagery before falling asleep

(Dahl, 1992). For a more complete discussion of narcolepsy. The prevalence is

estimated to be 90 in 100 000. Treatment can include a regular schedule of

naps; counseling of family, school and patient; and use of medications,

including stimulants and rapid eye move-ment-suppressant drugs such as

protriptyline. Dahl recommended beginning with standard, short-acting

stimulants, such as MPH, 5 mg b.i.d., and increasing the dose up to 30 mg

b.i.d. if need be.

Selection of a Stimulant Medication as a Treatment Modality

Deciding to Use Medication

The

decision to use stimulant medication in the treatment of ADHD employs different

criteria for each developmental stage. The criteria for use of stimulants in

school-age children and adolescents are well described in the DSM-IV-TR. More

difficulty arises when deciding whether to use these medications in preschool

children, adult patients, patients with mental retardation, or children with

ADHD and comorbid disorders.

Use of Psychostimulants in Children Younger than 6 Years

Unfortunately,

there are only a handful of published treatment studies on preschoolers. No

dose-ranging pharmacokinetic stud-ies have been done in this age group to

determine if younger chil-dren, with their larger liver-to-body size ratio,

might show more accelerated metabolism of psychostimulants than seen in older

children. Therefore, the optimal doses for this age group are not known. To

date there are no studies that would validate or refute clinicians’ concerns

that preschoolers suffer more pronounced stimulant withdrawal effects.

Adults

The

prevalence of ADHD in adults, its severity and indications for treatment are

issues that are not known. Although it had been assumed that children with ADHD

outgrow their problems, prospective follow-up studies have shown that ADHD

signs and symptoms continue into adult life for as many as 60% of children with

ADHD (American Psychiatric Association, 1980). However, only a small percent of

adults impaired by residual ADHD symptoms actually meet the full DSM-IV

childhood criteria for ADHD (Hill and Schoener, 1996). Adults with

concentration problems, impulsivity, poor anger control, job instability and

marital difficulties sometimes seek help for problems they believe to be the

manifestation of ADHD in adult life. Parents may decide that they themselves are

impaired by the same attentional and impulse control problems found during an

evaluation of their ADHD children.

A variety

of medications have been used to treat adults with ADHD. Physicians should be

cautious in the use of these agents until proof of efficacy is available. Of

particular concern is the danger of using psychostimulants in adults with

comorbid substance abuse disorder. It would be wise to use MPH because of its

relatively low abuse potential, and because it has been shown in controlled studies

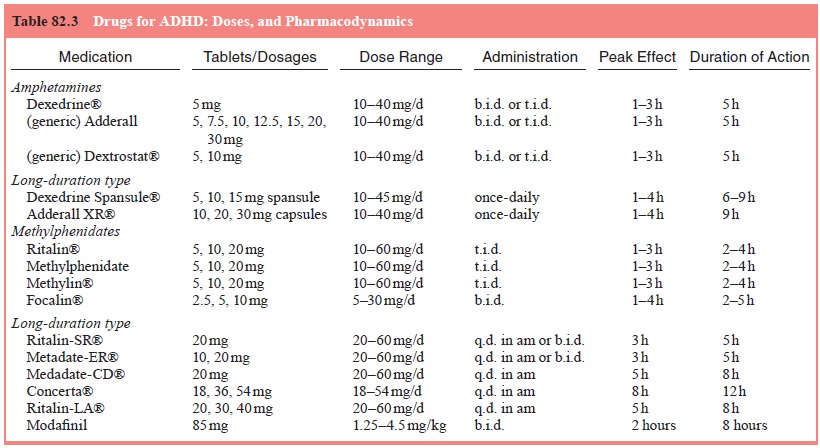

to significantly reduce the symptoms of ADHD in adults (see Table 82.3.)

Continuing Stimulant Treatment in Patients with Tic Disorders

Standard

package instructions for using MPH warns against its use in patients with tics

or in patients with a family history of tics. Patients with Tourette’s syndrome

often have comorbid ADHD. If the two conditions co-occur, concern arises that

stimulant treat-ment – because of its dopamine agonist actions – might unmask,

trigger, accelerate, or precipitate more severe tics.

Tics are

unacceptably worsened for a minority of comorbid children, although reversibly,

and the majority of such comorbid children can be treated cautiously with

low-to-moderate doses of stimulants, particularly MPH (Comings and Comings,

1987).

Patients with Mental Retardation

Many

stimulant treatment studies for school-age children with ADHD exclude children

with full-scale IQs below 70, who are considered to have mental retardation

(MR). This is unfortunate, for the signs of ADHD are far more prevalent in

children with IQs in the MR range (Aman et

al., 1991). Pharmacotherapy reviews involving patients with MR have

reported that institutionalized subjects with severe or profound MR respond

poorly to stimulants. However, studies involving community samples of children

with MR, have shown that these children do respond to MPH. It appears that

children with ADHD who have mild or moderate MR may be more vulnerable to

certain stimulant-related adverse side effects.

Does Comorbidity Affect the Indications for the Use of Stimulant Medication?

ADHD

children that are referred from other physicians may have other Axis I

psychiatric disorders. Extensive literature reviews report that ADHD co-occurs

with conduct and oppositional defi-ant disorder in 30 to 50% of cases, with

mood disorders in 15 to 75% of cases, with anxiety disorders in 25% of cases

and with learning disabilities in 15 to 30% of cases. Clinicians should be

aware that co-morbid ADHD/anxiety disorders may result in lesser response to

treatment more side effects.

Related Topics