Chapter: Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing : Substance Abuse

Treatment and Prognosis - Substance Abuse

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Current treatment modalities are based on the concept of alcoholism

(and other addictions) as a medical illness that is progressive, chronic, and

characterized by remissions and relapses (Jaffe & Anthony, 2005). Until the

1970s, organized treatment programs and clinics for substance abuse were

scarce. Before the illness of addiction was fully understood, most of the

society and even the medical com-munity viewed chemical dependency as a

personal prob-lem; the user was advised to “pull yourself together” and “get

control of your problem.” Founded in 1949, the Hazelden Clinic in Minnesota is

the noted exception; because of its success, many programs are based on the

Hazelden model of treatment.

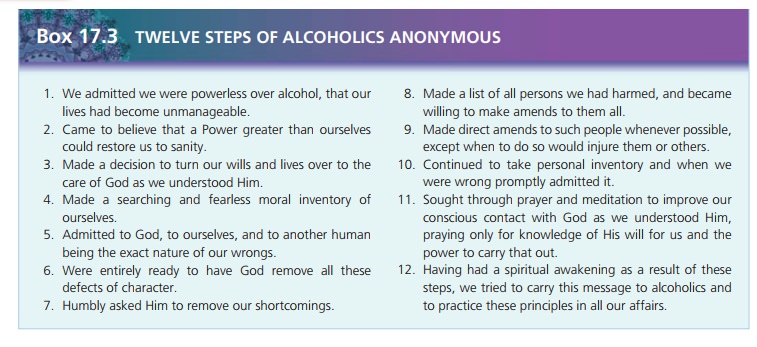

Today, treatment for substance use is available in a vari-ety of

community settings, not all of which involve health professionals. Alcoholics

Anonymous (AA) was founded in the 1930s by alcoholics. This self-help group

developed the 12-step program model

for recovery, which is based on the philosophy that total abstinence is

essential and that alcoholics need the help and support of others to maintain

sobriety. Key slogans reflect the ideas in the 12 steps, such as “one day at a

time” (approach sobriety one day at a time), “easy does it” (don’t get frenzied

about daily life and problems), and “let go and let God” (turn your life over

to a higher power). People who are early in recovery are encouraged to have a

sponsor to help them progress through the 12 steps of AA. Once sober, a member

can be a sponsor for another person.

Regular attendance at meetings is emphasized. Meet-ings are

available daily in large cities and at least weekly in smaller towns or rural

areas. AA meetings may be “closed” (only those who are pursuing recovery can

attend) or “open” (anyone can attend). Meetings may be educational with a

featured speaker; other meetings focus on a reading, daily meditation, or a

theme, and then offer the opportu-nity for members to relate their battles with

alcohol and to ask the others for help staying sober.

Many treatment programs, regardless of setting, use the 12-step

approach and emphasize participation in AA. They also include individual

counseling and a wide variety of groups. Group experiences involve education

about sub-stances and their use, problem-solving techniques, and cognitive

techniques to identify and to modify faulty ways of thinking. An overall theme

is coping with life, stress, and other people without the use of substances.

Although traditional treatment programs and AA have been successful

for many people, they are not effective for everyone. Some object to the

emphasis on God and spiri-tuality; others do not respond well to the

confrontational approach sometimes used in treatment or to identifying himself

or herself as an alcoholic or an addict. Women and minorities have reported

feeling overlooked or ignored by an essentially “white, male, middle-class”

organization. Treatment programs have been developed to meet these needs, such

as Women for Sobriety (exclusively for women) and Rainbow Recovery (for gay and

lesbian indi-viduals). AA groups may also be designated for women or gay and

lesbian people.

The 12-step concept of recovery has been used for other drugs as

well. Such groups include Narcotics Anonymous; Al-Anon, a support group for

spouses, partners, and friends of alcoholics; and AlaTeen, a group for children

of parents with substance problems. This same model has been used in self-help

groups for people with gambling problems and eating disorders.

Treatment Settings and Programs

Clients being treated for intoxication and withdrawal or

detoxification are encountered in a wide variety of medical settings from

emergency departments to outpatient clin-ics. Clients needing medically

supervised detoxification often are treated on medical units in the hospital

setting and then referred to an appropriate outpatient treatment setting when

they are medically stable.

Health professionals provide extended or outpatient treatment in

various settings, including clinics or centers offering day and evening

programs, halfway houses, resi-dential settings, or special chemical dependency

units in hospitals. Generally, the type of treatment setting selected is based

on the client’s needs as well as on his or her insur-ance coverage. For example,

for someone who has limited insurance coverage, is working, and has a

supportive fam-ily, the outpatient setting may be chosen first because it is

less expensive, the client can continue to work, and the family can provide

support. If the client cannot remain sober during outpatient treatment, then

inpatient treat-ment may be required. Clients with repeated treatment

experiences may need the structure of a halfway house with a gradual transition

into the community.

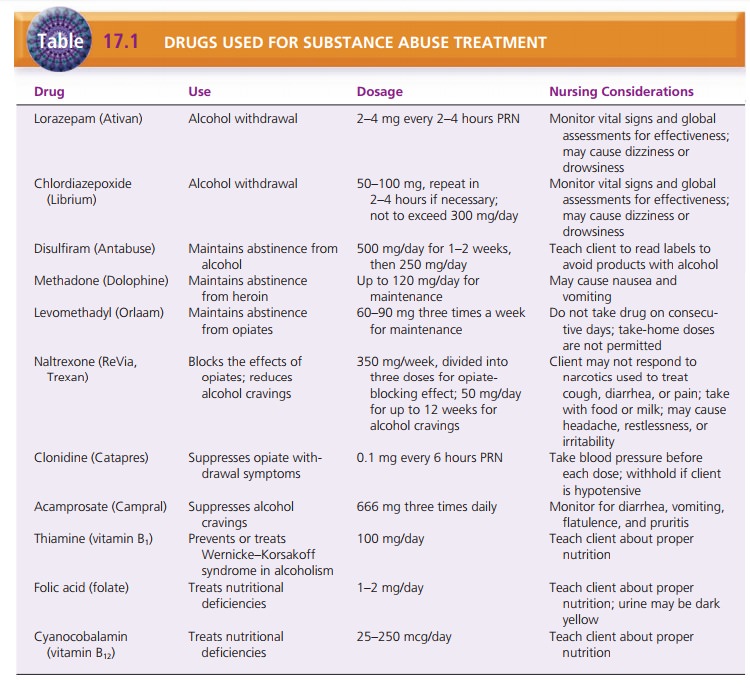

Pharmacologic Treatment

Pharmacologic treatment in substance abuse has two main purposes:

(1) to permit safe withdrawal from alcohol, sedative-hypnotics, and

benzodiazepines and (2) to prevent relapse. Table 17.1 summarizes drugs used in

substance abuse treatment. For clients whose primary substance is alcohol,

vitamin B1 (thiamine) often is prescribed to pre-vent or to treat

Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, which are

neurologic conditions that can result from heavy alcohol use.

Cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) and folic acid often are prescribed for

clients with nutritional deficiencies.

Alcohol withdrawal usually is managed with a benzodi-azepine

anxiolytic agent, which is used to suppress the symptoms of abstinence. The

most commonly used benzo-diazepines are lorazepam, chlordiazepoxide, and

diazepam. These medications can be administered on a fixed sched-ule around the

clock during withdrawal. Giving these medications on an as-needed basis

according to symptom parameters, however, is just as effective and results in a

speedier withdrawal (Lehne, 2006).

Disulfiram (Antabuse) may be prescribed to help deter clients from

drinking. If a client taking disulfiram drinks alcohol, a severe adverse

reaction occurs with flushing, a throbbing headache, sweating, nausea, and

vomiting. In severe cases, severe hypotension, confusion, coma, and even death

may result . The client also must avoid a wide variety of products that contain

alcohol such as cough syrup, lotions, mouthwash, perfume, aftershave vinegar,

and vanilla and other extracts. The client must read product labels carefully

because any product contain-ing alcohol can produce symptoms. Ingestion of

alcohol may cause unpleasant symptoms for 1 to 2 weeks after the last dose of

disulfiram.

Acamprosate (Campral) may be prescribed for clients recovering from

alcohol abuse or dependence to help reduce cravings for alcohol and decrease

the physical and emotional discomfort that occurs especially in the first few

months of recovery. These include sweating, anxiety, and sleep disturbances.

The dosage is two tablets (333 mg each) or 666 mg, three times a day. Persons

with renal impairment cannot take this drug. Side effects are reported as mild

and include diarrhea, nausea, flatulence, and pru-ritis. In one study,

acamprosate was found to be more effective with “relief cravers,” while

naltrexone (discussed later in this section) was more effective with “reward

cravers” (Mann, Kiefer, Spanagel, & Littleton, 2008).

Methadone, a potent synthetic opiate, is used as a sub-stitute for

heroin in some maintenance programs. The cli-ent takes one daily dose of

methadone, which meets the physical need for opiates but does not produce

cravings for more. Methadone does not produce the high associated with heroin.

The client has essentially substituted his or her addiction to heroin for an

addiction to methadone; however, methadone is safer because it is legal,

controlled by a physician, and available in tablet form. The client avoids the

risks of intravenous drug use, the high cost of heroin (which often leads to

criminal acts), and the ques-tionable content of street drugs.

Levomethadyl is a narcotic analgesic whose only pur-pose is the

treatment of opiate dependence. It is used in the same manner as methadone.

Naltrexone (ReVia) is an opioid antagonist often used to treat

overdose. It blocks the effects of any opioids that might be ingested, thereby

negating the effects of using more opioids. It also has been found to reduce

the cravings for alcohol in abstinent clients (Richardson et al., 2008). There

are four medications that are sometimes prescribed for the off-label use of

decreasing craving for cocaine. They are disulfiram (discussed earlier);

modafinil (Provigil), an antinarcoleptic; propranolol (Inderal), a -blocker;

and topiramate (Topamax), an anticonvulsant also used to sta-bilize moods and

treat migraines.

Clonidine (Catapres) is an alpha-2-adrenergic (a2-adrenergic) agonist used to

treat hypertension. It is given to clients with opiate dependence to suppress

some effects of withdrawal or abstinence. It is most effective against nausea,

vomiting, and diarrhea but produces modest relief from muscle aches, anxiety,

and restlessness (Lehne, 2006).

Ondansetron (Zofran), a 5-HT3 antagonist that blocks the

vagal stimulation effects of serotonin in the small intes-tine, is used as an

antiemetic. It has been used in young males at high risk for alcohol dependence

or with early-onset alcohol dependence. It is being studied for treatment of

methamphetamine addiction.

Dual Diagnosis

The client with both substance abuse and another psychi-atric

illness is said to have a dual diagnosis.

Dual diagnosis clients who have schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or

bipolar disorder present the greatest challenge to health care professionals.

It is estimated that 50% of people with a substance abuse disorder also have a

mental health diagnosis (Jaffe & Anthony, 2005). Traditional methods for

treatment of major psychiatric illness or primary substance abuse often have

little success in these clients for the following reasons:

·

Clients with a major psychiatric illness may have im-paired

abilities to process abstract concepts; this is a major barrier in substance

abuse programs. ![]()

![]() Substance use treatment emphasizes avoidance of

all psychoactive drugs. This may not be possible for the client who needs

psychotropic drugs to treat his or her mental illness.

Substance use treatment emphasizes avoidance of

all psychoactive drugs. This may not be possible for the client who needs

psychotropic drugs to treat his or her mental illness.

·

The concept of “limited recovery” is more acceptable in the

treatment of psychiatric illnesses, but substance abuse has no limited recovery

concept.

·

The notion of lifelong abstinence, which is central to substance

use treatment, may seem overwhelming and impossible to the client who lives

“day to day” with a chronic mental illness.

·

The use of alcohol and other drugs can precipitate psy-chotic

behavior; this makes it difficult for professionals to identify whether

symptoms are the result of active mental illness or substance abuse.

Clients with a dual diagnosis (substance use and mental illness) present challenges that traditional settings cannot meet. Studies of successful treatment and relapse prevention strategies for this population found several key elements that need to be addressed. These include healthy, nurturing, supportive living envi-ronments; assistance with fundamental life changes, such as finding a job and abstinent friends; connections with other recovering people; and treatment of their comorbid conditions. Clients identified the need for sta-ble housing, positive social support, using prayer or relying on a higher power, participation in meaningful activity, eating regularly, getting sufficient sleep, and looking presentable as important components of relapse prevention. Quetiapine (Seroquel) was used in one study to control alcohol cravings as well as moderating their psychiatric symptoms (Martinotti et al., 2008).

Related Topics