Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Substance Abuse: Alcohol Use Disorders

Treatment - Alcohol Use Disorders

Treatment

Goals, Setting and Costs of Treatment

When a determination has been made that an

individual is drink-ing excessively, the nature, setting and intensity of the

interven-tion must be determined in order to address the specific treatment

needs of the patient. Among heavy drinkers without evidence of alcohol

dependence, a brief intervention aimed at the reduction of drinking may

suffice. In contrast, among alcoholics, there are typically a variety of

associated disabilities, so it is necessary to address both the excessive

drinking and problems related to it.

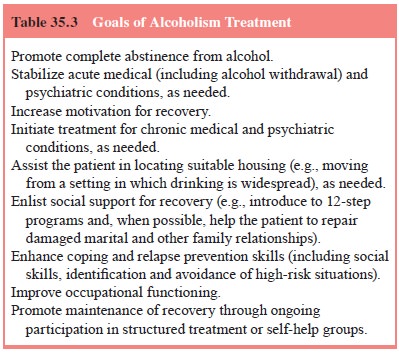

Consequently, alcoholism treatment is best conceived of as mul-timodal. Table

35.3 provides an overview of the goals of alcohol-ism treatment. It should be

noted that while total abstinence is a primary goal of treatment for persons

with alcohol dependence, moderate drinking can be considered as a goal for

persons with alcohol abuse.

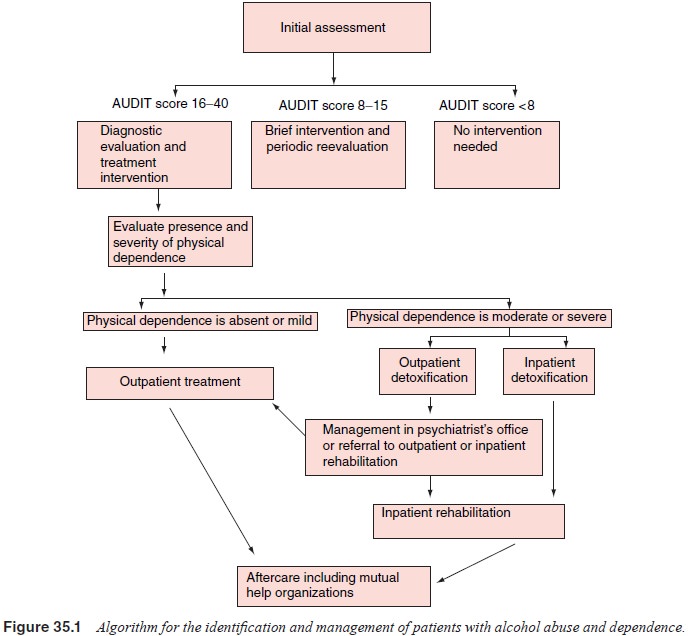

Figure 35.1 describes a process for the management

of patients with alcohol abuse and dependence. The algorithm is written from

the perspective of a community-based or consul-tation/liaison psychiatrist who

does not necessarily have spe-cialized training in addiction medicine.

Following the initial

assessment, using a screening test like the CAGE or

AUDIT, the patient is referred to either a diagnostic evaluation with a likely

treatment recommendation or a brief intervention with further monitoring. Brief

interventions are characterized by their low intensity and short duration. They

typically consist of one to three sessions of counseling and education. They

are intended to provide early intervention, before or soon after the onset of

alco-hol-related problems. Brief interventions seek to motivate high risk

drinkers to moderate their alcohol consumption, rather than promote total

abstinence with specialized treatment techniques. They are simple enough to be

delivered by primary care prac-titioners and are especially appropriate for

psychiatric patients whose at-risk drinking meets criteria for alcohol abuse

rather than dependence.

If the patient’s screening results and diagnostic

evaluation provide evidence of alcohol dependence, the next step is to

differ-entiate between mild and more severe levels of physical depend-ence to

determine the need for detoxification. If withdrawal risk is low, the patient

may be referred directly to outpatient therapy. If the withdrawal risk is

moderate or high, outpatient or inpatient detoxification is indicated.

There are a number of potentially life-threatening

condi-tions for which alcoholics are at increased risk. The presence of any of

the following requires immediate attention: acute alco- hol withdrawal (with

the potential for seizures and delirium tre-mens), serious medical or surgical

disease (e.g., acute pancreati-tis, bleeding esophageal varices) and serious

psychiatric illness (e.g., psychosis, suicidal intent). In the presence of any

of these emergent conditions, acute stabilization should be the first prior-ity

of treatment.

The presence of complicating medical or psychiatric

con-ditions is an important determinant of whether detoxification and

rehabilitation are initiated in an inpatient or an outpatient setting. Other

considerations are the alcoholic’s current living circum-stances and social

support network. Women with children are sometimes unwilling to enter

residential treatment unless their family needs are taken care of. Homeless

people may be eager to enter residential treatment even when their medical or

psychiat-ric condition does not warrant it.

In the alcoholic patient whose condition is

stabilized or in the patient without these complicating features, the major

focus should be on the establishment of a therapeutic alli-ance, which provides

the context within which rehabilitation can occur. The presence of a trusting

relationship facilitates the patient’s acknowledgement of alcohol-related

problems and encourages open consideration of different treatment op-tions. In

addition to participation in structured rehabilitation treatment, the patient

should be made aware of the widespread availability of Alcoholics Anonymous

(AA) and the wide di-versity of its membership.

Residential settings include hospital-based

rehabilitation programs, freestanding units and psychiatric units. With the

growth of managed care in the 1990s, there has been a dramatic reduction in the

average length of stay for residential treatment and a shift in emphasis to

less costly outpatient treatment set-tings. There is no consistent evidence

that intensive or inpatient residential treatment provides more benefit than

less intensive outpatient treatment, but for certain kinds of patients

residential treatment may have advantages (Finney and Monahan, 1996). In many

populations, outpatient programs produce results compara-ble to those of

inpatient programs.

Another approach to patient placement and treatment

matching is based on the notion that patients should initially be matched to

the least intensive level of care that is appropriate, and then stepped up to

more intensive treatment settings if they do not respond.

Despite treatment, some alcoholics relapse

repeatedly. For many emergency department personnel, the multiple recidivist

al-coholic has come to personify the disorder. For clinicians involved in the

delivery of alcoholism rehabilitation services, these individ-uals’ apparent

unresponsiveness to treatment may contribute to frustration and a sense of

futility. Presently, long-term residential treatment appears to be the only

option for alcoholics who do not respond to more limited efforts at

rehabilitation. Unfortunately, the availability of such care in many states is

limited as a conse-quence of the effort to deinstitutionalize psychiatric

patients.

Finally, the importance of continuing care by means

of af-tercare groups, and other mutual help organizations cannot be

overestimated.

Related Topics