Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Intraoperative Nursing Management

The Surgical Team

The Surgical Team

The surgical team consists of the

patient, the anesthesiologist or anesthetist, the surgeon, the intraoperative

nurses, and the surgical technologists. The anesthesiologist or nurse

anesthetist administers the anesthetic physical status throughout the

surgery. The surgeon and assistants scrub and perform the surgery. The

individual in the scrub role, either a nurse or surgical technologist, provides

sterile instruments and supplies to the surgeon during the procedure. The

circulating nurse coordinates the care of the patient in the operating room.

Care provided by the circulating nurse includes assisting with patient

positioning, preparing the patient’s skin for surgery, managing surgical

specimens, and documenting intraoperative events.

THE PATIENT

As the patient enters the operating room,

he or she may feel relaxed and prepared, or fearful and highly stressed. These

feelings depend very much on the amount and timing of preoperative sedation and

the patient’s level of fear and anxiety. Fears about loss of control, the

unknown, pain, death, changes in body structure or function, and disruption of

lifestyle all may contribute to a generalized anxiety. These fears can increase

the amount of anesthetic needed, the level of postoperative pain, and overall

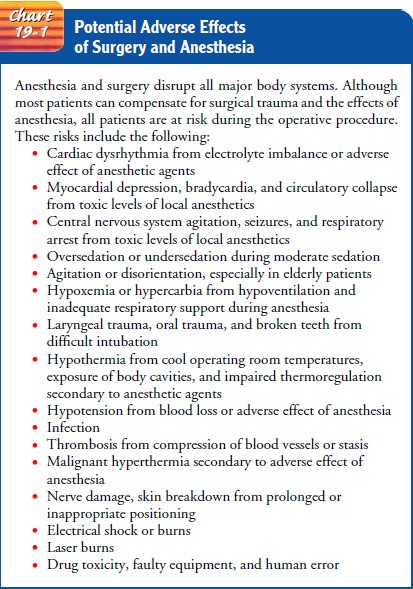

recovery time.The patient is also subject to several risks. Infection, failure

of the surgery to relieve symptoms, temporary or permanent complications

related to the procedure or the anesthetic, and deathare uncommon but potential

outcomes of the surgical experience (Chart 19-1). In addition to fears and

risks, the patient undergoing sedation and anesthesia temporarily loses both

cognitive func- tion and biologic self-protective mechanisms. Loss of pain

sense, reflexes, and ability to communicate subjects the intraoperative patient

to possible injury.

Gerontologic Considerations

Elderly patients face higher risks from

anesthesia and surgery than younger adult patients (Polanczyk et al., 2001).

Statistically,perioperative risk increases with each decade over 60 years,

often because of the increased incidence of coexisting disease. Modifications

tailored to the biologic changes of later life and the application of research

findings for this population can reduce the risks.

Biologic

variations of particular importance include age-related cardiovascular and

pulmonary changes (Townsend, 2002). The aging heart and blood vessels have

decreased ability to respond to stress. Reduced cardiac output and limited

cardiac reserve make the elderly patient vulnerable to changes in circulating

volume and blood oxygen levels. Excessive or rapid administration of

intravenous solutions may cause pulmonary edema. A sudden or prolonged drop in

blood pressure may lead to cerebral ischemia, thrombosis, embolism, infarction,

and anoxia. Reduced gas ex-change can lead to cerebral hypoxia.

The

elderly patient needs fewer anesthetics to produce anes-thesia and eliminates

the anesthetic agent over a longer time than a younger patient. As people age,

the percentage of lean body tis-sue decreases and fatty tissue steadily

increases (from age 20 years to 90 years). Anesthetic agents that have an

affinity for fatty tissue concentrate in body fat and the brain (Dudek, 2001).

Lower doses of anesthetic are appropriate for another reason. The older patient,

particularly when malnourished, may have low plasma protein lev-els. With

decreased plasma proteins, more of the anesthetic agent remains free or

unbound, and the result is more potent action.

Also

in elderly adults, body tissues made up predominantly of water and those with a

rich blood supply, such as skeletal muscle, liver, and kidneys, shrink. Reduced

liver size decreases the rate at which the liver can inactivate many

anesthetics, whereas de-creased kidney function slows elimination of waste products

and anesthetics. Other factors affecting the elderly surgical patient in the

intraoperative period include the following:

·

Impaired ability to increase

metabolic rate and impaired thermoregulatory mechanisms increase susceptibility

to hypothermia.

·

Bone loss (25% in women, 12% in men)

necessitates care-ful manipulation and positioning during surgery.

·

Reduced ability to adjust rapidly to

emotional and physical stress influences surgical outcomes and requires

meticulous observation of vital functions.

As

expected, mortality is higher with emergency surgery (com-monly required for

traumatic injuries) than with elective surgery, making continuous and careful

monitoring and prompt inter-vention especially important for older surgical

patients (Phippen & Wells, 2000).

Nursing Care

Throughout

surgery, nursing responsibilities include providing for the safety and

well-being of the patient, coordinating the op-erating room personnel, and

performing scrub and circulating activities. Because the patient’s emotional

state remains a con-cern, the care begun by preoperative nurses is continued by

the intraoperative nursing staff, who provide the patient with in-formation and

realistic reassurance. The nurse supports coping strategies and reinforces the

patient’s ability to influence out-comes by encouraging his or her active

participation in the plan of care.

In

the role of patient advocate, intraoperative nurses monitor factors that can

cause injury, such as patient position, equipment malfunction, and environmental

hazards, and they protect pa-tients’ dignity and interests while they are

anesthetized. Addi-tional responsibilities include maintaining surgical

standards of care, identifying existing patient risk factors, and assisting in

modifying complicating factors to help reduce operative risk (Phippen &

Wells, 2000).

THE CIRCULATING NURSE

The

circulating nurse (also known as the

circulator) must be a registered

nurse. He or she manages the operating room and protects the patient’s safety

and health by monitoring the ac-tivities of the surgical team, checking the

operating room con-ditions, and continually assessing the patient for signs of

injury and implementing appropriate interventions. The main re-sponsibilities

include verifying consent, coordinating the team, and ensuring cleanliness,

proper temperature, humidity, and lighting; the safe functioning of equipment;

and the availabil-ity of supplies and materials. The circulating nurse monitors

aseptic practices to avoid breaks in technique while coordinat-ing the movement

of related personnel (medical, radiography, and laboratory) as well as

implementing fire safety precautions (Phippen & Wells, 2000). The

circulating nurse monitors the patient and documents specific activities

throughout the oper-ation to ensure the patient’s safety and well-being.

Nursing ac-tivities directly relate to preventing complications and achieving

optimal patient outcomes.

THE SCRUB ROLE

Activities

of the scrub role include performing

a surgical hand scrub; setting up the sterile tables; preparing sutures,

ligatures, and special equipment (such as a laparoscope); and assisting the

surgeon and the surgical assistants during the procedure by anticipating the

instruments that will be required, such as sponges, drains, and other equipment

(Phippen & Wells, 2000). As the surgical incision is closed, the scrub

person and the cir-culator count all needles, sponges, and instruments to be

sure they are accounted for and not retained as a foreign body in the patient.

Tissue specimens obtained during surgery must also be labeled by the scrub

person and sent to the laboratory by the circulator.

THE SURGEON

The

surgeon performs the surgical procedure and heads the sur-gical team. He or she

is a licensed physician (MD), osteopath (DO), oral surgeon (DDS or DMD), or

podiatrist (DPM) who is specially trained and qualified. Qualifications may

include cer-tification by a specialty board, adherence to Joint Commission on

Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations ( JCAHO) standards, and adherence to

hospital standards and admitting practices and procedures (Fortunato, 2000).

THE REGISTERED NURSE FIRST ASSISTANT

The

registered nurse first assistant (RNFA) is another member of the operating room

staff. Although the scope of practice of the RNFA depends on each state’s nurse

practice act, the RNFA practices under the direct supervision of the surgeon.

RNFA re-sponsibilities may include handling tissue, providing exposure at the

operative field, suturing, and providing hemostasis. The en-tire process requires

a thorough understanding of anatomy and physiology, tissue handling, and the

principles of surgical asep-sis. The

competent RNFA needs to be aware of the objectives ofthe surgery, needs to have

the knowledge and ability to anticipate needs and to work as a skilled member

of a team, and needs to be able to handle any emergency situation in the

operating room (Fortunato, 2000; Rothrock, 1999).

THE ANESTHESIOLOGIST AND ANESTHETIST

An

anesthesiologist is a physician

specifically trained in the art and science of anesthesiology. An anesthetist is a qualified health care

professional who administers anesthetics. Most anesthetists are nurses who have

graduated from an accredited nurse anesthesia program and have passed

examinations sponsored by the American Association of Nurse Anesthetists to

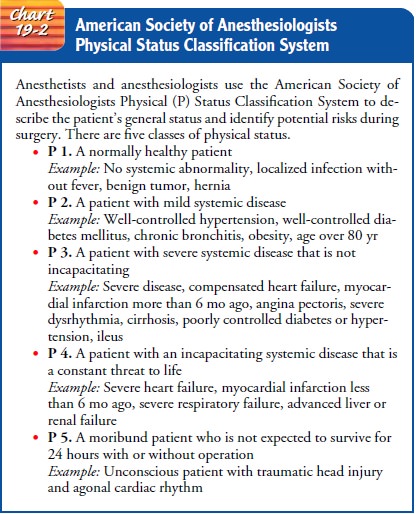

become a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). The anesthesiologist or

anesthetist in-terviews and assesses the patient prior to surgery, selects the

anes-thesia, administers it, intubates the patient if necessary, manages any

technical problems related to the administration of the anes-thetic agent, and

supervises the patient’s condition throughout the surgical procedure. Before

the patient enters the operating room, often at preadmission testing, the

anesthesiologist or anesthetist visits the patient to provide information and

answer questions. The type of anesthetic to be administered, previous reactions

to anes-thetics, and known anatomic abnormalities that would make air-way

management difficult are discussed. The anesthesiologist or anesthetist uses

the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification

System to determine the patient’s status (Chart 19-2).

When the patient arrives in the operating room, the anesthe-siologist or anesthetist reassesses the patient’s physical condition immediately prior to initiating anesthesia. The anesthetic is ad-ministered, and the patient’s airway is maintained either through a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) or an endotracheal tube. During surgery, the anesthesiologist or anesthetist monitors the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and respirations as well as the electrocar-diogram (ECG), blood oxygen saturation level, tidal volume, blood gas levels, blood pH, alveolar gas concentrations, and body temperature.

Monitoring by electroencephalography is some times

required. Levels of anesthetics in the body can also be de-termined; a mass

spectrometer can provide instant readouts of critical concentration levels on

display terminals. The device also assesses the patient’s ability to breathe

unassisted and indicates the need for mechanical assistance when ventilation is

poor and the patient is not breathing well independently.

Related Topics