Prose | By Edmund Hillary - The Summit | 12th English : UNIT 4 : Prose : The Summit

Chapter: 12th English : UNIT 4 : Prose : The Summit

The Summit

Prose

The

Summit

Edmund Hillary

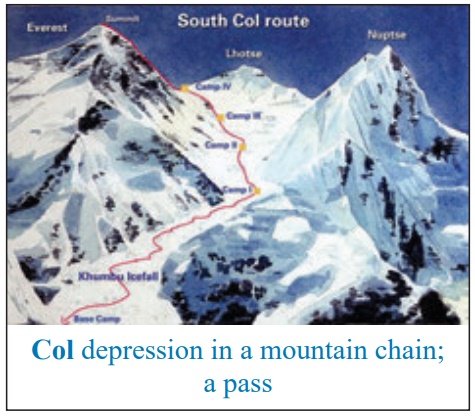

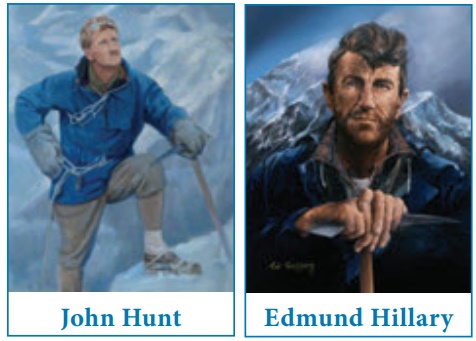

This prose unit is a slightly adapted excerpt from ‘The Ascent of Everest’ by John Hunt.

Sir Edmund Hillary’s own words,

tells how the summit of the Everest was reached.

On May 28 there were six

men at Camp 8 on the South Col: Edmund Hillary, Tenzing, George Lowe, Alfred

Gregory, and the two Sherpas, Pemba and Ang Nyima. But Pemba was too ill to

climb. The others, heavily laden, climbed that day to a height of 27,900 feet.

Here, Hillary and Tenzing put up a little tent, and watched their three

companions go down the ridge, back towards the South Col.

As the sun set, Hillary

and Tenzing crawled into the tent, put on all their warm clothing, and wriggled

into their sleeping bags. Next morning, at 4 a.m. on May 29, they began to get

ready for the climb.

1. We started up our cooker and drank large quantities of lemon

juice and sugar, and followed this with our last tin of sardines on biscuits. I

dragged our oxygen sets into the tent, cleaned the ice off them, and then

rechecked and tested them.

2. I had removed my

boots, which had become wet the day before, and they were now frozen solid. So

I cooked them over the fierce flame of the Primus and managed to soften them

up. Over our down clothing we donned our windproof and on to our hands we

pulled three pairs of gloves – silk, woollen, and windproof.

3. At 6.30 a.m. we crawled out of that tent into the snow, hoisted

our 30 lb. of oxygen gear on to our backs, connected up our masks and turned on

the valves to bring life-giving oxygen into our lungs. A few good deep breaths

and we were ready to go. Still a little worried about my cold feet, I asked

Tenzing to move off.

4. Tenzing kicked steps

in a long traverse

back towards the ridge,

and we

reached its crest where

it forms a great snow bump at about 28000 feet. From here the ridge narrowed to

a knife-edge and, as my feet were now warm, I took over the lead.

5. The soft snow made a

route on top of the ridge both difficult and dangerous, which sometimes held my

weight but often gave way suddenly. After several hundred feet, we came to a

tiny hollow, and found there the two oxygen bottles left on the earlier attempt

by Evans and Bourdillon. I scraped the ice off the gauges and was relieved to

find that they still contained several hundred litres of oxygen – enough to get

us down to the South Col if used sparingly.

6. I continued making the trail on up the ridge, leading up for

the last 400 feet to the southern summit. The snow on this face was dangerous,

but we persisted in our efforts to beat a trail up it.

7. We made frequent changes of lead. As I was stamping a trail in

the deep snow, a section around me gave way and I slipped back through three or

four of my steps. I discussed with Tenzing the advisability of going on, and

he, although admitting that he felt unhappy about the snow conditions, and

finished with his familiar phrase “Just as you wish”.

8. I decided to go on; and we finally reached firmer snow higher

up, and then chipped steps up the last steep slopes and cramponed on to the

South Peak. It was now 9 a.m.

9. We cut a seat for ourselves just below the South Summit and

removed our oxygen apparatus. As our first partly-full bottle of oxygen was now

exhausted, we had only one full bottle left. Our apparatus was now much

lighter, weighing just over 20 lb., and as I cut steps down off the South

Summit I felt a sense of freedom and well being.

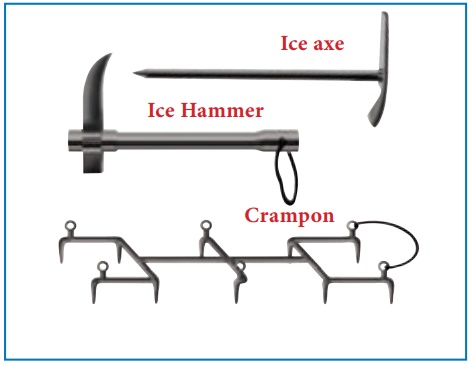

10. As my ice-axe bit

into the first steep slope of the ridge, my high hopes were realized. The snow

was crystalline and firm. Two or three blows of the ice - axe produced a step

large enough even for our over-sized High Altitude boots, and a firm thrust of

the ice-axe would sink it half-way up the shaft, giving a solid and comfortable

belay.

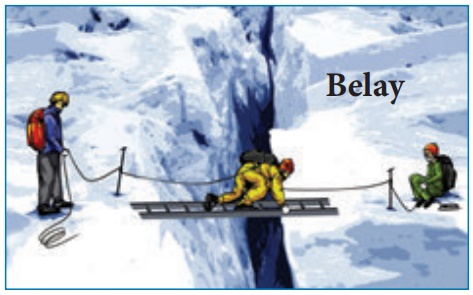

11. We moved one at a time. I would cut a forty foot line of

steps, Tenzing belaying me while I worked. Then in turn I would sink my shaft

and put a few loops of the rope around it, and Tenzing, protected against a breaking step, would

move up to me. Then once again as he belayed me I would go on cutting.

12. In a number of places the overhanging ice cornices were very large indeed,

and in order to escape them I cut a line of steps down to where the snow met

the rocks on the west. It was a great thrill to look straight down this

enormous rock face and to see, 8000 feet below us, the tiny tents of Camp 4 in

the Western Cwm. Scrambling on the rocks and cutting handholds on the snow, we were able to shuffle

past these difficult portions.

13. On its east side was

another great cornice; and running up the full forty feet of the step was a

narrow crack between the cornice and the rock. Leaving Tenzing to belay me as

best he could, I jammed my way into this crack. Then, kicking backwards, I sank

the spikes of my crampons deep into the frozen snow behind me and levered

myself off the ground.

14. Taking advantage of

every little rock hold, and all the force of knee, shoulder, and arms I could

muster, I literally cramponed backwards up the crack, praying that the cornice

would remain attached to the rock. My progress although slow was steady. As

Tenzing paid out the rope, I inched my way upwards until I could reach over the

top of the rock and drag myself out of the crack on to a wide ledge.

15. For a few moments I lay regaining my breath, and for the first

time really felt the fierce determination that nothing now could stop us

reaching the top. I took a firm stance on the ledge and signalled to Tenzing to

come on up. As I heaved hard on the rope, Tenzing wriggled his way up the crack,

and finally collapsed at the top like a giant fish when it has just been hauled

from the sea after a terrible struggle.

16. The ridge continued

as before: giant cornices on the right; steep rock sloped on the left. The

ridge curved away to the right and we have no idea where the top was. As I cut

around the back of one hump, another higher one would swing into view. Time was

passing and the ridge seemed never-ending.

17. Our original zest had now quite gone, and it was turning more

into a grim struggle. I then realized that the ridge ahead, instead of rising,

now dropped sharply away. I looked upwards to see a narrow snow ridge running

up to a snowy summit. A few more whacks of the ice-axe in the firm snow and we

stood on top.

18. My first feelings were of relief– relief that there were no

more steps to cut, no more ridges to traverse, and no more humps to tantalize us with hopes of

success. I looked at Tenzing. In spite of the balaclava helmet, goggles, and

oxygen mask – all encrusted with long icicles–that concealed his face, there

was no disguising his grin of delight as he looked all around him. We shook

hands, and then Tenzing threw his arm around my shoulders and we thumped each

other on the back until we were almost breathless. It was 11.30 a.m. The ridge

had taken us two and a half hours, but it seemed like a lifetime.

19. To the east was our giant neighbour Makalu, unexplored and

unclimbed. Far away across the clouds, the great bulk of Kanchenjunga loomed on

the horizon. To the west, we could see the great unexplored ranges of Nepal

stretching off into the distance.

20. The most important photograph, I felt, was a shot down the

North Ridge, showing the North Col and the old route which had been made famous

by the struggles of those great climbers of the 1920’s and 1930’s. After ten

minutes, I realized that I was becoming rather clumsy-fingered and slow-

moving. So I quickly replaced my oxygen set.

21. Meanwhile, Tenzing had made a little hole in the snow, and in

it he placed various small articles of food– a bar of chocolate, a packet of biscuits,

and a handful of lollies. Small offerings, indeed, but at least a token gift to

the Gods that all devout Buddhists believe have their home on this lofty

summit.

22. While we were together on the South Col two days before,

Colonel Hunt had given me a small crucifix which he had asked me to take to the

top. I, too, made a hole in the snow and placed the crucifix beside Tenzing’s

gifts.

23. After fifteen minutes, I moved down off the summit on to our

steps. Wasting no time, we cramponed along our tracks, spurred by the urgency of diminishing oxygen.

We scrambled cautiously over the rock traverse, moved one at a time over shaky

snow sections and finally cramponed up our steps and back on to the South Peak.

24. We were now very tired, but moved down to the two reserve

cylinders on the ridge. As we were only a short distance from camp, and had a

few litres of oxygen left in our own bottles, we carried the extra cylinders

down, and reached our tent on its crazy platform at 2 p.m.

25. With a last look at the camp that had served us so well, we

turned downwards with dragging feet and set ourselves to the task of safely

descending the ridge to the South Col.

26. The time passed as

in a dream. Two figures came towards us and met us a couple of hundred feet

above the camp. They were George Lowe and Wilfrid Noyce, laden with hot soup

and emergency oxygen. Just short of the tent my oxygen ran out. We had had

enough to do the job, but by no means too much.

27. We crawled into the

tent and, with a sigh of delight, collapsed into our sleeping-bags, while the

tents flapped and shook under the perpetual South Col gale.

John Hunt who led the

expedition states that “It was an unforgettable day.” They had climbed to the

top! There were shouts of joy, handshakes and hugs for the two heroes. Their

happiness and pride showed, how these men had shared in the achievement, that

was brilliantly concluded by Tenzing and Hillary. The adventure was over.

The story of the ascent

of Everest is one of comradeship and teamwork, formed through dangers and

difficulties met and overcome together. Perhaps, after the climbing of this

great mountain, others will find their own “Everests”, for there are still many

opportunities for adventure. Some are close at hand, others are far away in

distant lands.

Not all adventures are

exciting. Nor is adventure to be found only upon a mountain. There are

“Everests” to be climbed in our everyday life. Given the selflessness and

resolve which enabled men to climb Everest, there is no height, no depth, that

the spirit of man, guided by a higher Spirit, cannot attain.

About The Author

Sir Edmund Percival

Hillary (20 July 1919 – 11 January 2008) was a New Zealand mountaineer,

explorer, and philanthropist. He served in the Royal New Zealand Air Force as a

navigator during World War II. Following his ascent of Everest, Hillary devoted

himself to assisting the Sherpa people of Nepal through the Himalayan Trust,

which he established. High Adventure, No Latitude for Error, Nothing Venture, Nothing

Win, View from the Summit: The Remarkable Memoir by the First Person to Conquer

Everest are some of his famous works.

Related Topics