Prose | By George L Hart - The Status of Tamil as a Classical Language | 12th English : UNIT 5 : Prose : The Status of Tamil as a Classical Language

Chapter: 12th English : UNIT 5 : Prose : The Status of Tamil as a Classical Language

The Status of Tamil as a Classical Language

Prose

The

Status of Tamil as a Classical Language

George

L Hart

Mr. George L Hart, a

linguistic anthropologist, endeavours to make a comparative analysis of

classical languages of the world. Now, let’s see which languages emerge as the

best amongst equals, from his point of view.

April 11, 2000

Professor Maraimalai has

asked me to write regarding the position of Tamil as a classical language, and

I am delighted to respond to his request.

I have been a Professor

of Tamil at the University of California, Berkeley, since 1975 and am currently

holder of the Tamil Chair at that institution. My degree, which I received in

1970, is in Sanskrit, from Harvard, and my first employment was as a Sanskrit

professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in 1969. Besides Tamil and

Sanskrit, I know the classical languages of Latin and Greek and have read

extensively in their literatures in the original. I am also well-acquainted

with comparative linguistics and the literatures of modern Europe.

Let me state unequivocally that, by any criteria

one may choose, Tamil is one of the greatest classical literatures and

traditions of the world.

The reasons for this are

many; let me consider them one by one.

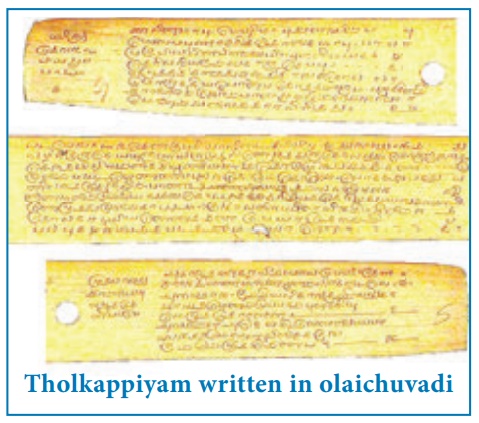

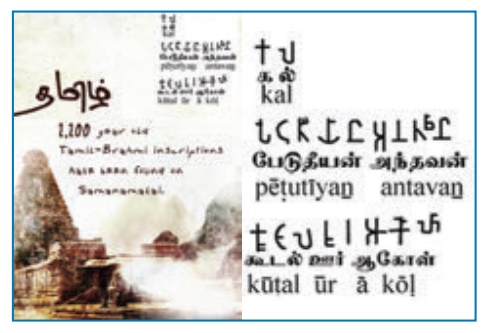

First, Tamil is of considerable antiquity. It predates the

literatures of other modern Indian languages by more than a thousand years. Its

oldest work, the Tolkappiyam, contains parts that, judging from the earliest

Tamil inscriptions, date back to about 200

BCE. The greatest works of ancient Tamil, the Sangam anthologies and the Pattuppattu,

date to the first two centuries of the current era. They are the first great secular body of poetry written

in India, predating Kalidasa’s works by two hundred years.

Second, Tamil

constitutes the only literary tradition indigenous to India that is not derived from Sanskrit.

Indeed, its literature arose before the influence of Sanskrit in the South

became strong, and so is qualitatively different from anything we have in

Sanskrit or other Indian languages. It has its own poetic theory, its own

grammatical tradition, its own esthetics, and, above all, a large body of literature

that is quite unique. It shows a sort of Indian sensibility that is quite

different from anything in Sanskrit or other Indian languages, and it contains

its own extremely rich and vast intellectual tradition.

Third, the quality of

classical Tamil literature is such that it is fit to stand beside the great

literatures of Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Chinese, Persian and Arabic. The subtlety and profundity of its works, their

varied scope (Tamil is the only pre modern Indian literature to treat the subaltern extensively), and their universality qualify

Tamil to stand as one of the greatest classical traditions and literatures of

the world. Everyone knows the Tirukkural, one of the world’s greatest works on

ethics; but this is merely one of a myriad of major and extremely varied works that comprise the

Tamil classical tradition. There is not a facet of human existence that is not explored and illuminated by this great literature.

Finally, Tamil is one of the primary independent sources of modern Indian culture and tradition. I have written extensively on the influence of a Southern tradition on the Sanskrit poetic tradition. But equally important, the great sacred works of Tamil Hinduism, beginning with the Sangam Anthologies, have undergirded the development of modern Hinduism. Their ideas were taken into the Bhagavata Purana and other texts (in Telugu and Kannada as well as Sanskrit), whence they spread all over India. Tamil has its own works that are considered to be as sacred as the Vedas and that are recited alongside Vedic mantras in the great Vaisnava temples of South India. And just as Sanskrit is the source of the modern Indo-Aryan languages, classical Tamil is the source language of modern Tamil and Malayalam. As Sanskrit is the most conservative and least changed of the Indo-Aryan languages, Tamil is the most conservative of the Dravidian languages, the touchstone that linguists must consult to understand the nature and development of Dravidian.

I am well aware of the

richness of the modern Indian languages — I know that they are among the most fecund and productive

languages on earth, each having begotten a modern (and often medieval)

literature that can stand with any of the major literatures of the world. Yet

none of them is a classical language. Like English and the other modern

languages of Europe (with the exception of Greek), they rose on preexisting traditions rather late

and developed in the second millennium.

To qualify as a classical tradition, a language must fit several criteria: it should be ancient, it should be an independent tradition that arose mostly on its own not as an offshoot of another tradition, and it must have a large and extremely rich body of ancient literature. Unlike the other modern languages of India, Tamil meets each of these requirements.

It is extremely old (as old as

Latin and older than Arabic); it arose as an entirely independent tradition,

with almost no influence from Sanskrit or other languages; and its ancient

literature is indescribably vast and rich.

The status of Tamil as

one of the greatest classical languages of the world is something that is patently obvious to anyone who

knows the subject. To deny that Tamil is a classical language is to deny a

vital and central part of the greatness and richness of Indian culture.

Sincerely,

George L. Hart

About The Author

George Luzerne Hart is a

professor of Tamil language at the University of California, Berkeley. His work

focuses on classical Tamil literature and on identifying the relationships

between Tamil and Sanskrit literature. In 2015, the Government of India awarded

him the title of Padma Shri, the third highest civilian honour. He studied

Latin, Greek, Sanskrit and several modern and European languages.

Related Topics