by James Grover Thurber - The Night the Ghost Got In | 10th English: UNIT 2 : Prose: The Night the Ghost Got In

Chapter: 10th English: UNIT 2 : Prose: The Night the Ghost Got In

The Night the Ghost Got In

Prose

The Night the Ghost Got In

James Grover Thurber

Imagination of odd things always leads to absolute humour. Read

the lesson and enjoy the narrator's experience with his grandfather who creates

chaos and laughter with his imaginative stories.

The ghost that got into our house on the night of November 17,

1915, raised such a hullabaloo of misunderstandings that I am sorry I didn’t just let it keep on

walking, and go to bed. Its advent caused my mother to throw a shoe through a

window of the house next door and ended up with my grandfather shooting a patrolman. I am sorry, therefore,

as I have

said, that I ever paid

any attention to the footsteps.

They began about a quarter past one o’clock in the morning, a

rhythmic, quick-cadenced walking around the dining-room table. My mother was

asleep in one room upstairs, my brother-Herman in another, grandfather was in

the attic, in the old walnut bed which, as you will remember, once fell

on my father. I had just stepped out of the bathtub and was busily rubbing

myself with a towel when I heard the steps. They were the steps of a man

walking rapidly around the dining-table downstairs. The light from the bathroom

shone down the back-steps, which dropped directly into the dining-room; I could

see the faint shine of plates on the plate-rail; I couldn’t see the table. The

steps kept going round and round the table; at regular intervals a board

creaked, when it was trod upon. I supposed at first that it was my father or my

brother Roy, who had gone to Indianapolis but were expected home at any time. I

suspected next that it was a burglar. It did not enter my mind until later that

it was a ghost.

a. Where was the author when he heard the noise?

b. What did the narrator think the unusual sound was?

After the walking had gone on for perhaps three minutes, I tiptoed

to Herman’s room. ‘Psst!’ I hissed, in the dark, shaking him. ‘Awp’, he said,

in the low, hopeless tone of a despondent beagle – he always half suspected

that something would ‘get him’ in the night. I told him who I was. ‘There’s

something downstairs!’ I said. He got up and followed me to the head of the back

staircase. The steps had ceased. Herman looked at me in some alarm: I had only

the bath towel around my waist. He wanted to go back to bed, I gripped his arm.

‘There’s something down there!’ I said. Instantly the steps began

again, circled the dining-room table like a man running, and started up the

stairs towards us, heavily, two at a time. The light still shone palely down

the stairs; we saw nothing coming; we only heard the steps. Herman rushed to

his room and slammed the door. I slammed shut the door at the stairs top and

held my knee against it.

After a long minute, I slowly opened it again. There was nothing

there. There was no sound. None of us ever heard the ghost again.

The slamming of the doors had aroused mother: she peered out of her room. ‘What

on earth are you boys doing?’ she demanded. Herman ventured out of his room.

‘Nothing,’ he said, gruffly, but he was, in colour, a light green. ‘What was all that running

around downstairs?’ said mother. So she had heard the steps, too! We just

looked at her. ‘Burglars!’ she shouted, intuitively. I tried to quieten her by starting lightly

downstairs.

‘Come on, Herman,’ I said.

‘I’ll stay with mother,’ he said. ‘She’s all excited.’

I stepped back onto the landing.

‘Don’t either of you go a step,’ said mother. ‘We’ll call the

police.’ Since the phone was downstairs, I didn’t see how we were going to call

the police -- nor did I want the police – but mother made one of her quick,

incomparable decisions. She flung up a window of her bedroom which faced the

bedroom windows of the house of a neighbour, picked up a shoe, and whammed it through a pane of

glass across the narrow space that separated the two houses. Glass tinkled into

the bedroom occupied by a retired engraver named Bodwell and his wife. Bodwell

had been for some years in rather a bad way and was subject to mild ‘attacks’.

Almost everybody we knew or lived near had some kind of attacks.

c. What were the various sounds the brothers heard when they

went downstairs?

d. Who were the narrator neighbours ?

It was now about two o’clock of a moonless night; clouds hung

black and low. Bodwell was at the window in a minute, shouting frothing a

little, shaking his fist. ‘We’ll sell the house and go back to Peoria,’ we

could hear Mrs. Bodwell saying. It was some time before mother ‘got through’ to

Bodwell. ‘Burglars!’ she shouted. ‘Burglars in the house!’ Herman and I hadn’t

dared to tell her that it was not burglars but ghosts, for she was even more

afraid of ghosts than of burglars. Bodwell at first thought that she meant

there were burglars in his house, but finally he quieted down and called the

police for us over an extension phone by his bed. After he had disappeared from

the window, mother suddenly made as if to throw another shoe, not because there

was further need of it but, as she later explained, because the thrill of

heaving a shoe through a window glass had enormously taken her fancy. I

prevented her.

The police were on hand in a commendably short time: a Ford sedan

full of them, two on motorcycles, and a patrol wagon with about eight in it and

a few reporters. They began banging at our front door. Flashlights shot streaks

of gleam up and down the walls, across the yard, down the walk between our

house and Bodwell’s. ‘Open up!’ cried a hoarse voice. ‘We’re men from

Headquarters!’ I wanted to go down and let them in, since there they were, but

mother wouldn’t hear of it. ‘You haven’t a stitch on,’ she pointed out. ‘You’d

catch your death.’ I wound the towel around me again. Finally the cops put

their shoulders to our big heavy front door with its thick bevelled glass and broke it in:

I could hear a rending of wood and a splash of glass on the floor of the hall. Their

lights played all over the living-room and crisscrossed nervously in the dining

-room, stabbed into hallways, shot up the front stairs and finally up the back.

They caught me standing in my towel at the top. A heavy policeman bounded up

the steps. ‘Who are you?’ he demanded. ‘I live here,’ I said.

e. How did the Bodwells react, when a shoe was thrown into their

house?

f. What did the Bodwells think when they heard the mother shout

The officer in charge reported to mother. ‘No sign of nobody,

lady,’ he said. ‘Musta got away – whatt’d he like?’ ‘There were two or three of

them,’ mother said, ‘whooping and carrying on slamming doors.’ ‘Funny,’ said

the cop. ‘All ya windows and door was locked on the inside tight as a tick.’

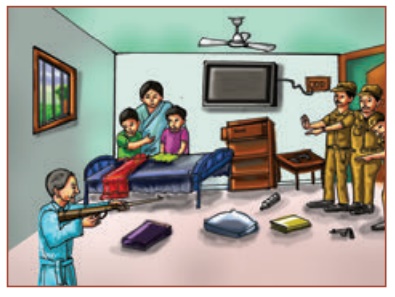

Downstairs, we could hear the tromping of the other police. Police

were all over the place; doors were yanked open, drawers were yanked open, windows were

shot up and pulled down, furniture fell with dull thumps. A half-dozen

policemen emerged out of the darkness of the front hallway upstairs. They began

to ransack the floor; pulled beds away from walls, tore clothes off hooks in

the closets, pulled suitcase and boxes off shelves. One of them found an old zither that Roy had won in a

pool tournament. ‘Looky here, Joe,’ he said, strumming it with a big paw. The

cop named Joe took it and turned it over. ‘What is it?’ he asked me. ‘It’s an

old zither our guinea pig used to sleep on,’ I said. It was true that a pet guinea pig we

once had would never sleep anywhere except on the zither, but I should never

have said so. Joe and the other cop looked at me a long time. They put the

zither back on a shelf.

‘No sign o’ nothing’, said the cop who had first spoken to mother,

‘The lady seems hysterical.’ They all nodded, but said nothing; just looked at

me. In the small silence we all heard a creaking in the attic. Grandfather was

turning over in bed. ‘What’s that?’ snapped Joe. Five or six cops sprang for

the attic door before I could intervene or explain. I realized that it would be

bad if they burst in on grandfather unannounced, or even announced. He was

going through a phase in which he believed that General Meade’s men, under

steady hammering by Stonewall Jackson, were beginning to retreat and even

desert.

When I got to the attic, things were pretty confused.

Grandfather had evidently jumped to the conclusion that the police were

deserters from Meade’s army, trying to hide away in his attic. He bounded out

of bed wearing a long flannel nightgown over long woolen pants, a nightcap, and

a leather jacket around his chest. The cops must have realized at once that the

indignant white-haired old man belonged to the house, but they had no chance to

say so. ‘Back, ye cowardly dog!’ roared grandfather. ‘Back t’ the lines ye

goodaam Lily -livered cattle!’ With that, he fetched the officer who found the

zither a flat – handed smack alongside his head that sent him sprawling. The

others beat a retreat, but not enough; grandfather grabbed zither’s gun from

its holster and let fly. The report seemed to crack the rafters; smoke filled

the attic. A cop cursed and shot his hand to his shoulder. Somehow, we all

finally got downstairs again and locked the door against the old gentleman. He

fired once or twice more in the darkness and then went back to bed. ‘That was

grandfather’, I explained to Joe, out of breath. ‘He thinks you’re deserter.’

‘I’ll say he does,’ said Joe.

g. What was the grandfather wearing?

h. What conclusions did

grandfather jump to when he saw the cops?

The cops were reluctant to leave without getting their hand on

somebody besides grandfather; the night had been distinctly a defeat for them.

Furthermore, they obviously didn’t like the ‘layout’; something looked – and I

can see their viewpoint – phony. They began to poke into things again. A

reporter, a thin-faced, wispy man, came up to me. I had put on one of mother’s

dress, not being able to find anything else. The reporter looked at me with

mingled suspicion and interest. ‘Just what the hell is the real lowdown here,

Bud?’ he asked. I decided to be frank with him. ‘We had ghosts,’ I said. He gazed

at me a long time as if I were a slot machine into which he had, without

results, dropped a coin. Then he walked away. The cops followed him, the one

grandfather shot holding his now-bandaged arm, cursing and blaspheming. ‘I’m

gonna get my gun back from that old bird,’ said the zither- cop. ‘Yeh,’ said

Joe, ‘You – and who else?’ I told them I would bring it to the station house

the next day.

‘What was the matter with that one policeman?’ mother asked, after

they had gone. ‘Grandfather shot him,’ I said. ‘What for?’ she demanded. I told

her he was a deserter. ‘Of all things!’ said mother. ‘He was such a

nice-looking young man’.

‘Grandfather was fresh as a daisy and full of jokes at breakfast

next morning. We thought at first he had forgotten all about what had happened,

but he hadn’t. Over his third cup of coffee, he glared at Herman and me. ‘What

was the idee of all them cops tarryhootin’ round the house last night?’ he

demanded. 'None of you bothered to leave a bottle of water beside my bed. Do

you ever realize what it cost for a thirsty man to look for water in the dining

room last night?" He had us there.

i. Were the policemen willing to leave the house?

j. What made the reporter gaze at the author?

About the Author

James Grover Thurber (1894–1961) was an American cartoonist, author, humourist,

journalist, playwright, and celebrated wit. He was best known for his cartoons

and short stories published mainly in The New Yorker magazine, such as

"The Catbird Seat", and collected in his numerous books. He was one

of the most popular humourists of his time, as he celebrated the comic

frustrations and eccentricities of ordinary people.

Related Topics