Emergence of New Kingdoms in South India | Term 1 Unit 3 | History | 7th Social Science - The Later Cholas | 7th Social Science : History : Term 1 Unit 3 : Emergence of New Kingdoms in South India: Later Cholas and Pandyas

Chapter: 7th Social Science : History : Term 1 Unit 3 : Emergence of New Kingdoms in South India: Later Cholas and Pandyas

The Later Cholas

The Later Cholas

Learning Objectives

•

To trace the origin of the later Cholas and the later Pandyas

•

To know about the prominent rulers of both the kingdoms

•

To acquaint with their administrative system

•

To understand the social, economic and cultural development during their reign

Introduction

The

Cholas are one among the popular and well-known Tamil monarchs in the history

of South India. The elaborate state structure, the extensive irrigation

network, the vast number of temples they built, their great contributions to

art and architecture and their overseas exploits have given them a pre-eminent

position in history.

Revival of the Chola Rule

The

ancient Chola kingdom reigned supreme with the Kaveri delta forming the core

area of its rule and with Uraiyur (present-day Tiruchirappalli) as its

capital. It rose to prominence during the reign of Karikala but

gradually declined under his successors. In the 9th century Vijayalaya, ruling

over a small territory lying north of the Kaveri, revived the Chola Dynasty. He

conquered Thanjavur and made it his capital. Later Rajendra I and his

successors ruled the empire from Gangaikonda Cholapuram, the newly built

capital.

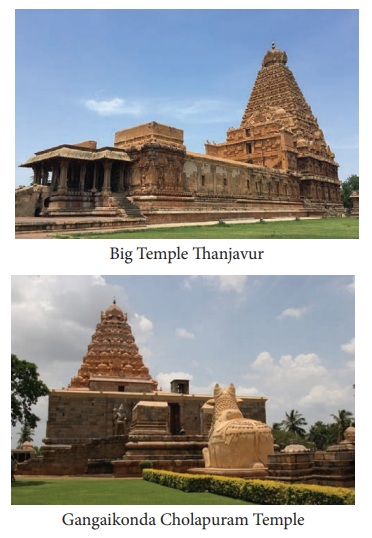

Rajaraja

I (A.D. (CE) 985 - 1016) was the most powerful ruler of Chola empire and also

grew popular beyond his times. He established Chola authority over large parts of

South India. His much-acclaimed naval expeditions led to the expansion of

Cholas into the West Coast and Sri Lanka. He built the famous Rajarajeswaram

(Brihadeshwara) Temple in Thanjavur. His son and successor, Rajendra Chola I

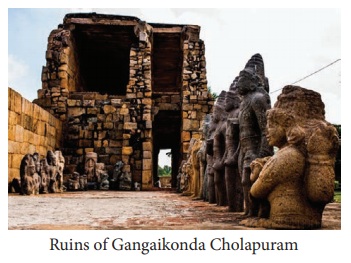

(A.D. (CE) 1016 - 1044, matched his father in his ability to expand the empire. The Chola empire

remained a powerful force in South India during his reign. After his accession

in A.D. (CE) 1023, his striking military expedition was to northern India,

capturing much territory there. He proclaimed himself the Gangaikondan

(conqueror of the Gangai region). The Gangaikonda Cholapuram temple was built

to commemorate his victories in North India. The navy of Rajendra Chola enabled

him to conquer the kingdom of Srivijaya (southern Sumatra). Cholas’ control

over the seas facilitated a flourishing overseas trade.

Decline of the Chola

Empire

Rajendra

Chola’s three successors were not capable rulers. The third successor

Veerarajendra’s son Athirajendra was killed in civil unrest. With his death

ended the Vijayalaya line of Chola rule.

Matrimonial alliances

between the Cholas and the Eastern Chalukyas began during the reign of Rajaraja

I. His daughter Kundavai was married to Chalukya prince Vimaladitya. Their son

was Rajaraja Narendra who married the daughter of Rajendra Chola named

Ammangadevi. Their son was Kulothunga I.

On

hearing the death of Athirajendra, the Eastern Chalukya prince Rajendra

Chalukya seized the Chola throne and began the rule of Chalukya-Chola dynasty

as Kulothunga I. Kulothunga established himself firmly on the Chola throne soon

eliminating all the threats to the Chola Empire. He avoided unnecessary wars

and earned the goodwill of his subjects. But Kulothunga lost the territories in

Ceylon. The Pandya territory also began to slip out of Chola control.

Kanchipuram was lost to the Telugu Cholas. The year 1279 marks the end of Chola

dynasty when King Maravarman Kulasekara Pandyan I defeated the last king

Rajendra Chola III and established the rule of the Pandyas in present-day Tamil

Nadu.

Administration

The

central administration was in the hands of king. As the head of the state, the

king enjoyed enormous powers. The king’s orders were written down in palm

leaves by his officials or inscribed on the temple walls. The kingship was

hereditary in nature. The ruler selected his eldest son as the heir apparent.

He was known as Yuvaraja. The Yuvarajas were appointed as Governors in the

provinces mainly for administrative training.

The

Chola rulers established a well-organised system of administration. The empire,

for administrative convenience, was divided into provinces or mandalams.

Each mandalam was sub-divided into naadus. Within each naadu, there were

many kurrams (groups of villages). The lowest unit was the gramam (village).

Local Governance

Local

administration worked through various bodies such as Urar, Sabhaiyar,

Nagarattar and Nattar. With the expansion of agriculture, numerous peasant

settlements came up on the countryside. They were known as Ur. The Urar, who

were landholders acted as spokesmen in the Ur. Sabhaiyar in Brahman villages

also functioned in carrying out administrative, financial and judicial

functions. Nagarattar administered the settlement of traders. However, skilled

artisans like masons, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, weavers and potters also lived

in Nagaram. Nattar functioned as an assembly of Nadu and decided all the

disputes and issues pertaining to Nadu.

The

assemblies in Ur, Sabha, Nagaram and Nadu worked through various committees.

The committees took care of irrigation, roads, temples, gardens, collection of

revenue and conduct of religious festivals.

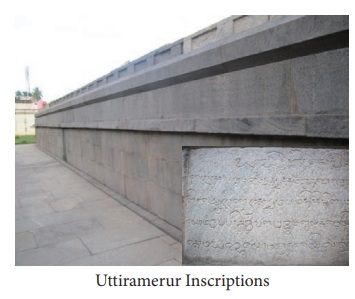

Uttiramerur Inscriptions

Uttiramerur presently in Kanchipuram

district was a Brahmadeya village (land grants given to Brahmins). There

is a detailed description of how members were elected to the committees of the

village sabha in the inscriptions found there. One member was to be elected

from each ward. There were 30 wards in total. The eligibility to contest was to

men in the age group of 35–70, well-versed in vedic texts and scriptures, and

also owned land and house. The process of election was as follows: The names of

qualified candidates from each ward were written on the palm-leaf slips and put

into a pot. The eldest of the assembly would engage a boy to pull out one slip

and declare his name. Various committees were decided in this way.

Revenue

The

revenue of the Chola state came mainly from the land. The land tax was known as

Kanikadan. The Chola rulers carried out an elaborate survey of land in order to

fix the government’s share of the land revenue. One-third of produce was

collected as land tax. It was collected mostly in kind. In addition to land

tax, there were taxes on profession and tolls on trade.

Social Structure Based on

Land Relations

The

Chola rulers gifted tax-free lands to royal officials, Brahmins, temples

(devadana villages) and religious institutions. Land granted to Jain

institutions was called pallichchandam. There were also of vellanvagai

land and the holders of this land were called Vellalars. Ulu-kudi, a

sub-section of Vellalar, could not own land but had to cultivate Brahmadeya

and vellanvagai lands. The holders of vellanvagai land retained melvaram

(major share in harvest). The ulu-kudi got kil-varam (lower

share). Adimai (slaves) and panicey-makkal (labourers) occupied

the lowest rung of society. In the intermediate section came the armed men and

traders.

Irrigation

Cholas

gave importance to irrigation. The 16-mile long embankment built by Rajendra

Chola in Gangaikonda Cholapuram is an illustrious example. Vati-vaykkal,

a criss-cross channel, is a traditional type of harnessing rain water in the

Cauvery delta. Vati is a drainage channel and a vaykkal is the

supply channel. The commonly owned village channel was called ur-vaykkal.

The nadu level vaykkal is referred to as nadu-vaykkal. The turn-system

was in practice in distributing the water.

Religion

Chola

rulers were ardent Saivites. Hymns, in praise of the deeds of Lord Siva, were

composed by the Saiva saints, the Nayanmars. NambiyandarNambi codified them,

which came to be known as the Thirumurai.

Temples

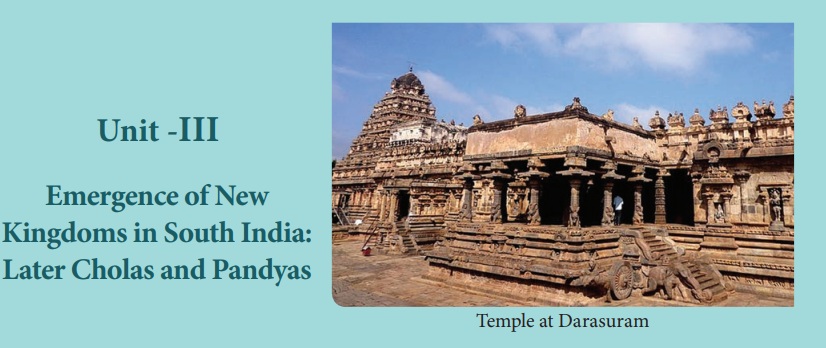

The

Chola period witnessed an extensive construction of temples. The temples in

Thanjavur, Gangaikonda Cholapuram and Darasuram are the repository of

architecture, sculpture, paintings and iconography of the Chola art. Temples

during the Chola period were not merely places of worship. They were the

largest landholders. Temples promoted education, and devotional forms of art such

as dance, music and drama. The staff of the temples included temple officials,

dancing girls, musicians, singers, players of musical instruments and the

priests.

Cholas as Patrons of

Learning

Chola

kings were great patrons of learning. Rajendra I established a Vedic college at

Ennayiram (now in Villupuram District). There were 340 students learning the

Vedas, grammar and Upanishads under 14 teachers. This example was later

followed by his successors and as a result two more such colleges had been

founded, at Tirubuvanai near present-day Puducherry and Tirumukkoodal in

present-day Chengalpattu district, in 1048 and 1067 respectively. The great

literary works Periyapuranam and Kamba Ramayanam belong to this

period.

Trade

There was a flourishing trade during the Chola period. Trade was carried out by two guild-like groups: anju-vannattar and mani-gramattar. Anju-vannattar comprised West Asians, Arabs, Jews, Christians and Muslims.

They

were maritime traders and settled on the port towns all along the West Coast.

It is said that mani-gramattar were the traders engaged in inland trade.

In due course, both groups merged under the banner of ai-nutruvar and disai-ayirattu-ai-nutruvar

functioning through the head guild in Ayyavole, Karnataka. This

ai-nutruvar guild operated the maritime trade covering South-East Asian

countries. Through overseas trade with South-East Asian countries elephant

tusks, coral, transparent glass, betel nuts, cardamom, opaque glass, cotton

stuff with coloured silk threads were imported. The items exported from here

were sandalwood, ebony, condiments, precious gems, pepper, oil, paddy, grains

and salt.

Related Topics