Chapter: Modern Medical Toxicology: Corrosive(Caustic) Poisons: Mineral Acids (Inorganic Acids)

Sulfuric Acid - Corrosive(Caustic) Poisons

Sulfuric Acid

Synonym

Oil

of vitriol; Oleum; Battery acid.

Physical Appearance

Sulfuric acid is a heavy, oily, colourless, odourless, non-fuming liquid (Fig 5.1). It is hygroscopic, i.e. it has great affinity for water with which it reacts violently, giving off intense heat Sulfuric acid is mainly used in two forms:

·

Commercial concentrated sulfuric

acid is usually a 93–98% solution in water.

·

Fuming sulfuric acid is a solution

of sulfur trioxide in sulfuric acid.

Uses/ Sources

Sulfuric

acid is probably the most widely used industrial chem-ical in most parts of the

world including India.

·

It is used as a feedstock in the

manufacture of a number of chemicals, e.g. acetic acid, hydrochloric acid,

phosphoric acid, ammonium sulfate, barium sulfate, copper sulfate, phenol,

synthetic fertilisers, dyes, pharmaceuticals, detergents, paint, etc

·

Storage batteries utilise sulfuric

acid as an electrolyte.

·

Sulfuric acid is also used in the

leather, fur, food processing, wool, and uranium industries, for gas drying,

and as a laboratory reagent.

·

Sulfuric acid can be formed in smog

from the photo- chemical oxidation of sulfur dioxide to sulfur trioxide and

subsequent reaction with water. It is a major component of acid rain.

Usual Fatal Dose

About

20 to 30 ml of concentrate sulfuric acid. Deaths have been reported with

ingestion of as little as 3.5 ml.

Toxicokinetics

Systemic

absorption of sulfuric acid is negligible.

Mode of Action

Produces

coagulation necrosis of tissues on contact.

Clinical Features

·

Burning pain from the mouth to the stomach. Abdominal pain

is often severe.

·

Intense thirst. However, attempts at drinking water usually

provoke retching.

·

The vomitus is brownish or blackish in colour due to altered

blood (coffee grounds vomit), and may

contain shreds of the charred wall of the stomach.

·

![]() If there is coincidental damage to the larynx during

swal-lowing or due to regurgitation, there may be dysphonia, dysphagia, and

dyspnoea.

If there is coincidental damage to the larynx during

swal-lowing or due to regurgitation, there may be dysphonia, dysphagia, and

dyspnoea.

·

Tongue is usually swollen, and blackish or brownish in

colour. Teeth become chalky white. There may be constant drooling of saliva

which is indicative of oesophageal injury.

·

There is often acid spillage while swallowing with

conse-quent corrosion of the skin of the face (especially around the mouth),

neck, and chest (Fig 5.2). Burnt

skin appears dark brown or black.

·

Features of generalised shock are usually apparent.

·

Renal failure and decreased urine output can occur after

several hours of uncorrected circulatory collapse.

·

Because it is a strong acid, exposure to sulfuric acid may

produce metabolic acidosis, particularly following ingestion. Acidosis may be

due to severe tissue burns and shock, as well as absorption of acid.

·

Leukocytosis is common after exposure to strong mineral

acids.

·

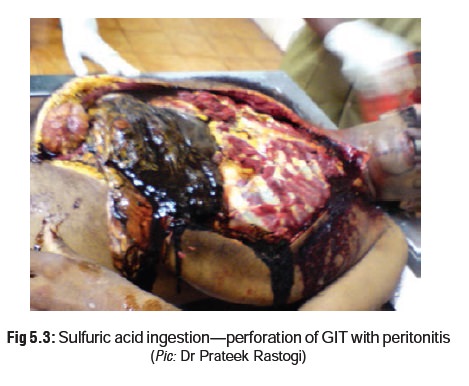

If perforation of stomach occurs, a severe form of chemical

peritonitis can result. Rarely, perforation of duodenum (or even further down

the small intestine) may occur.

·

If the patient recovers, there are usually long-term

sequelae such as stricture formation which may lead to pyloric obstruction,

antral stenosis, or an hour glass deformity of the stomach. The oesophagus may

also be involved resulting in stenosis. There are indications of increased

propensity for carcinomas.

·

Contact with the eyes can cause severe injury including

conjunctivitis, periorbital oedema, corneal oedema and ulceration, necrotising

keratitis, and iridocyclitis.

·

Chronic

Exposure –

a.Occupational exposure to sulfuric acid mist can cause erosion of teeth over a period of time, as also increased incidence of upper respiratory infections.

b.

Sulfuric acid can react with other substances to form mutagenic and possibly

carcinogenic products such as alkyl sulfates. Case reports suggest that chronic

exposure to sulfuric acid fumes may be linked to carcinoma of the vocal cords

and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Occupational exposure to sulfuric acid may

contribute to cases of laryngeal cancer.

Diagnosis

·

Litmus

test: The pH of the saliva can be tested with a litmuspaper to

determine whether the chemical ingested is an acid or an alkali (turns red in

acid, and blue in alkaline solution).*

·

Fresh stains in clothing may be

tested by adding a few drops of sodium carbonate. Production of effervescence

(bubbles) is indicative of an acid stain.

·

If vomitus or stomach contents are

available, add 10% barium chloride. A heavy white precipitate forms which is

insoluble on adding 1 ml nitric acid.

Treatment

·

Respiratory distress due to

laryngeal oedema should be treated with 100% oxygen and cricothyroidotomy.**

·

Some authorities recommend administration

of water or milk if the patient is seen within 30 minutes of ingestion (120–240

ml in an adult, 60–120 ml in a child). But no attempt must be made at

neutralisation with alkalis, since the resulting exothermic reaction can cause

more harm than benefit. Studies indicate that even administration of buffering

agents such as antacids can produce significant exothermic reaction.

·

Remove all contaminated clothes and

irrigate exposed skin copiously with saline. Non-adherent gauze and wrapping

may be used. Deep second degree burns may benefit from topical silver

sulfadiazine.

·

Eye injury should be dealt with by

retraction of eyelids and prolonged irrigation for at least 15 to 30 minutes

with normal saline or lactated Ringer’s solution, or tap water if nothing else

is available. Anaesthetic agents and lid retractors may be necessary. It is

desirable to continue with the irigation until normal pH of ocular secretions

is restored (7.4), which can be tested with litmus paper or urine dipstick.

Slit lamp examination is mandatory after decontamination, to assess the extent

of corneal damage.

·

The following measures are contraindicated: oral feeds, induction

of vomiting, stomach wash, and use of acti-vated charcoal.

·

Oral

feeds: Depends on degree of damage as assessedby early endoscopy.

The following is a rough guide—

a.

Mild (grade I): may have oral feedings on first day.

b.

Moderate (grade II): may have liquids after 48 to 72 hours.

c.

Severe (grade III): jejunostomy tube feedings after 48 to 72 hours.

·

Administration of steroids has been shown to delay stricture

formation (in animals) when given within 48 hours of acid ingestion, but the

practice is generally not recommended because of increased risk of perforation.

a. In case it is embarked upon, the

dosage recommended is 60 to 100 mg/day of prednisolone for the first 4 days,

followed by 40 mg/day for the next 4 days, and finally 20 mg/day for the

subsequent 7 to 10 days. In children, the appropriate dose is 2 mg/kg/day.

b.Alternatively 0.1 mg/kg of

dexamethasone or 1 to 2 mg/kg of prednisone can be given for

3 weeks and then tapered off.

·

Administer antibiotics only if

infection occurs. Prophy-lactic use is not advisable unless corticosteroid

therapy is being undertaken.

·

Since there is often severe pain,

powerful analgesics such as morphine may have to be given.

·

The use of flexible fibreoptic

endoscopy is now stan-dard practice in the first 24 to 48 hours of ingestion to

assess the extent of oesophageal and gastric damage. If there are

circumferential 2nd or 3rd degree burns, an exploratory laparotomy should be

performed. If gastric necrosis is present, an oesophagogastrectomy may have to be done.

·

Emergency laparotomy is mandatory if there is perfora-tion

or peritonitis.

·

If the patient recovers, there may be long-term sequelae

such as stenosis and stricture formation.* Follow-up is therefore essential to

look for signs of obstruction—nausea, anorexia, weight loss. Surgical

procedures such as dilatation, colonic bypass, and oesophagogastrostomy may

have to be undertaken.

Box 5.1 Management of Ocular Caustic Exposures

The most

important first-aid measure for all patients with ocular caustic exposures

should be immediate decontamination by irrigation, using copious amounts of

water or any readily available safe aqueous solution such as normal saline,

lactated Ringer’s solution, or balanced salt solution. An ocular topical

anaesthetic is usually required for effective irrigation. A complete irrigation

must be done including the conjunctival recesses, internal and external palpebral

surfaces, and corneal and bulbar conjunctiva. Lid retraction is invariably

necessary. While concern has been expressed over the use of aqueous solutions

for ocular irrigation in the case of exposure to substances which react with

water leading to heat or mechanical injury (e.g. white phosphorus), there are

hardly any documented case reports where this has actually happened.

The

duration of ocular irrigation varies with the nature of exposure. After

exposure to acids or alkalies, normalisation of the conjunctival pH is often

suggested as a useful endpoint. A minimum of 2 litres of irrigant per affected

eye should be used before any assessment of pH is done. After waiting for 5 to

10 minutes, the pH of the lower conjunctival fornix is checked. Thereafter, rechecks

are done in cycles until the pH reaches 7.5 to 8.

Adjunctival

treatment of ocular burns include application of topical antibiotic providing

antistaphylococcal and antipseudomonal coverage, cycloplegics which not only

reduce pain from ciliary spasm, but also decrease the likelihood of posterior

synechiae forma-tion, and the use of eye patches and systemic analgesics.

Topical anaesthetic agents are not desirable. Topical steroids may help lessen

the inflammation, but can interfere with healing and so must not be used for

more than the first 7 days.

In every

case of caustic ocular exposure, consultation with an ophthalmologist is

essential after administration of first-aid and decontamination, to assess

visual acuity, and to undertake slit lamp examination for detecting corneal

damage. It may take 48 to 72 hours after the burn to assess correctly the

degree of ocular damage. The basis of such an evaluation is the size of the

corneal epithelial defect, the degree of corneal opacification and extent of

limbal ischaemia.

•

Grade 1: Corneal epithelial damage; no

ischaemia.

•

Grade 2: Cornea hazy; iris details

visible, ischaemia less than one-third of limbus.

•

Grade 3: Total loss of corneal

epithelium; stromal haze obscures iris details; ischaemia of one-third to one-half

of limbus.

•

Grade 4: Cornea opaque; iris and pupil

obscured, ischaemia affects more than one-half of limbus.

Autopsy Features

· Corroded areas of skin and mucous

membranes appear brownish or blackish. Teeth appear chalky white.

· Stomach mucosa shows the consistency

of wet blotting paper.

· There may be inflammation, necrosis,

or perforation of the GI tract (Fig 5.3).

Forensic Issues

· Accidental poisoning may arise from

mistaken identity since sulfuric acid resembles glycerine and castor oil. It is

therefore imperative that it is stored in a distinctive bottle, clearly

labelled, and kept in a safe place.

· Sulfuric acid is a rare choice for

either suicide or homicide.

· In addition to routine viscera and body

fluids, a portion of corroded skin should be cut out, placed in rectified

spirit or absolute alcohol and sent for chemical analysis. Stained clothing

must also be sent (preservative not necessary).

·

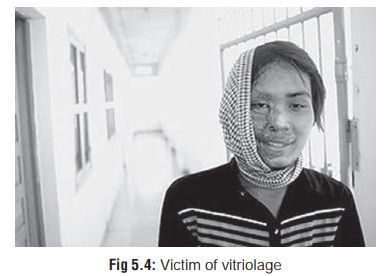

Vitriolage:

o This

term refers to the throwing of an acid on to the face or body of a person in

order to disfigure or blind him (Fig 5.4).

The motive is usually revenge or jealousy.

o Though

sulfuric acid is commonly used (hence the term vitriolage which is derived from “oil of vitriol”), other acids are

also employed. In fact any corrosive which is easy to hand may be used,

including organic acids, alkalis, and irritant plant juices.

o Going

by newspaper reports, vitriolage is a fairly common crime in India, though it

is regarded as a serious offence (grievous

hurt), and carries stiff punishment.*

Related Topics