Chapter: Software Architectures : Introduction and Architectural Drivers

Specifying Quality Attribute Requirements

Specifying Quality Attribute Requirements

A quality attribute requirement

should be unambiguous and testable. We use a common form to specify all quality

attribute requirements. This has the advantage of emphasizing the commonalities

among all quality attributes. It has the disadvantage of occasionally being a force-fit for some aspects

of quality attributes.

Our

common form for quality attribute expression has these parts:

■■ Stimulus. We use the term “stimulus” to

describe an event arriving at the system. The stimulus can be an

event to the performance community, a user operation to the usability

community, or an attack to the security community. We use the same term to

describe a motivating action for developmental qualities. Thus, a stimulus for modifiability

is a request for a modification; a stimulus for testability is the completion

of a phase of development.

■■ Stimulus source. A stimulus must have a source—it

must come from some-where.

The source of the stimulus may affect how it is treated by the system. A request from a trusted user

will not undergo the same scrutiny as a request by an untrusted user.

■■ Response. How the system should respond to

the stimulus must also be specified. The response consists

of the responsibilities that the system (for runtime qualities) or the

developers (for development-time qualities) should perform in response to the

stimulus. For example, in a performance scenario, an event arrives (the

stimulus) and the system should process that event and generate a response. In

a modifiability scenario, a request for a modification arrives (the stimulus)

and the developers should implement

the modification—without side effects—and then test and deploy the

modification.

■■ Response measure. Determining whether a response is

satisfactory— whether the requirement is

satisfied—is enabled by providing a response measure. For performance this

could be a measure of latency or throughput; for modifiability it could be the

labor or wall clock time required to make, test, and deploy the modification.

These

four characteristics of a scenario are the heart of our quality attribute

specifications. But there are two more characteristics that are important:

environment and artifact.

■■ Environment. The environment of a requirement is the set of

circumstances in which the scenario takes place.

The environment acts as a qualifier on the stimulus. For example, a request for

a modification that arrives after the code has been frozen for a release may be

treated differently than one that arrives before the freeze. A failure that is

the fifth successive failure of a component may be treated differently than the

first failure of that component.

■■ Artifact. Finally, the artifact is the

portion of the system to which the requirement applies. Frequently

this is the entire system, but occasionally specific portions of the system may be called out. A

failure in a data store may be treated differently than a failure in the

metadata store. Modifications to the user interface may have faster response

times than modifications to the middleware.

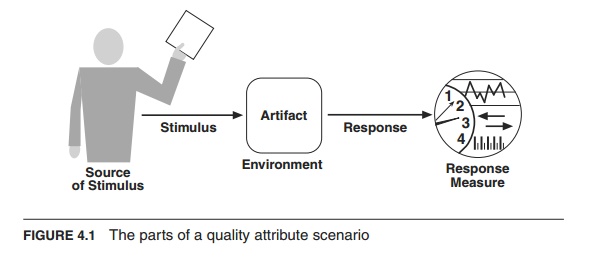

To

summarize how we specify quality attribute requirements, we capture them

formally as six-part scenarios. While it is common to omit one or more of these

six parts, particularly in the early stages of thinking about quality

attributes, knowing that all parts are there forces the architect to consider

whether each part is relevant.

In

summary, here are the six parts:

1.

Source of stimulus. This is some entity (a human, a

computer system, or any other actuator) that generated

the stimulus.

2.

Stimulus. The stimulus is a condition that

requires a response when it ar-rives at a system.

3.

Environment. The stimulus occurs under certain

conditions. The system may be in an overload condition or

in normal operation, or some other rele-vant state. For many systems, “normal” operation can refer

to one of a num-ber

of modes. For these kinds of systems, the environment should specify in which

mode the system is executing.

4.

Artifact. Some artifact is stimulated. This

may be a collection of systems, the whole system, or some piece or

pieces of it.

5.

Response. The response is the activity

undertaken as the result of the arrival of the stimulus.

6.

Response measure. When the response occurs, it

should be measurable in some fashion so that the

requirement can be tested.

We

distinguish general quality attribute scenarios

(which we call “general scenarios” for short)—those that are system independent

and can, potentially, pertain to any system—from concrete quality attribute scenarios

(concrete scenarios)—those that are specific to

the particular system under consideration.

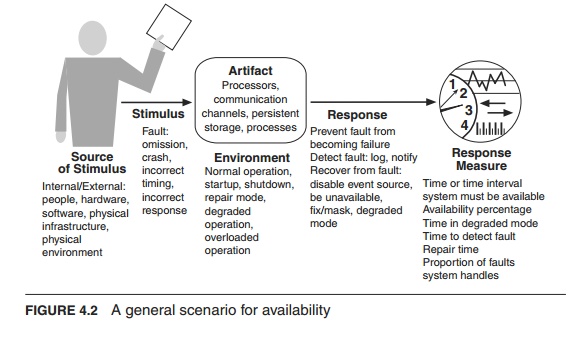

We can characterize quality

attributes as a collection of general scenarios. Of course, to translate these

generic attribute characterizations into requirements for a particular system,

the general scenarios need to be made system specific. Detailed examples of

these scenarios will be given in Chapters 5–11. Figure 4.1 shows the parts of a

quality attribute scenario that we have just discussed. Figure 4.2 shows an example of a

general scenario, in this case for availability.

Related Topics