Chapter: Software Architectures : Introduction and Architectural Drivers

Functional Requirements - Software Architectures

General

Requirements

Capturing

requirements is difficult. Capturing architecturally significant requirements is

particularly

difficult. This article discusses the root causes of this difficulty, and

suggests a systematic approach to capturing architectural requirements to

ensure that these elusive, and yet extremely important, system specifications

are not overlooked.

What Is

an Architectural Requirement?

Because this article focuses on an approach to

gathering requirements of particular significance to the architecture of a

system1, let's start with the definition of an architectural requirement.

Rational Unified Process® (RUP®) gives the following

definition for any requirement:

A

requirement describes a condition or capability to which a system must conform;

either derived directly from user needs, or stated in a contract, standard,

specification, or other formally imposed document.

An architectural

requirement, in turn, is any requirement that is architecturally significant,

whether this significance be implicit or explicit. Implicit architectural

requirements are those requirements that have particular attributes. For

example, any high-risk, high-priority, or low-stability requirement could be

considered to be architecturally significant. However, this article will focus

primarily on explicit requirements, which are often technical in nature. The

following are examples of explicit architectural requirements:

·

The product will be localized

(support multiple human languages).

·

The persistence will be handled

by a relational database.

·

The database will be Oracle 8i.

·

The system will run seven days a

week, twenty-four hours per day.

·

An online help system is

required.

·

All presentation logic will be

written in Visual Basic.

As you may notice, these requirements are extremely

mixed. Some are functional, some non-functional; some are independent of

technical mechanisms, others are not. What we need is a systematic approach

that provides a framework for classifying architectural requirements, which

ensures that valuable statements such as those listed above are not overlooked.

The

FURPS+ System for Classifying Requirements

One such classification system was devised by

Robert Grady at Hewlett-Packard.2 It goes by the acronym FURPS+ which represents:

·

Functionality

·

Usability

·

Reliability

·

Supportability

The "+" in FURPS+ also helps us to

remember concerns such as:

·

Design requirements

·

Implementation requirements

·

Interface requirements

·

Physical requirements

Let's look at each category in detail

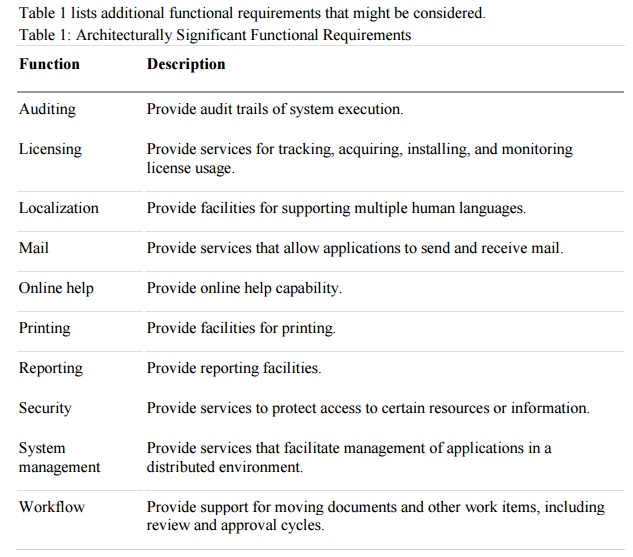

The Functional Requirements Specification documents

the operations and activities that a system must be able to perform.

Functional Requirements should include:

·

Descriptions of data to be

entered into the system

·

Descriptions of operations

performed by each screen

·

Descriptions of work-flows

performed by the system

·

Descriptions of system reports or

other outputs

·

Who can enter the data into the

system

·

How the system meets applicable

regulatory requirements

The Functional Requirements Specification is

designed to be read by a general audience. Readers should understand the

system, but no particular technical knowledge should be required to understand

the document.

Rapid

Functional Requirement Creation

Examples of Functional Requirements

Functional requirements should include functions

performed by specific screens, outlines of work-flows performed by the system,

and other business or compliance requirements the system must meet. Download an

example functional requirements specification or use these quick examples below.

Interface

requirements

·

Field 1 accepts numeric data

entry.

·

Field 2 only accepts dates before

the current date.

·

Screen 1 can print on-screen data

to the printer.

Business

Requirements

· Data must be entered before a request can be approved.

·

Clicking the Approve button moves

the request to the Approval Workflow.

·

All personnel using the system

will be trained according to internal SOP AA-101.

Regulatory/Compliance Requirements

·

The database will have a

functional audit trail.

·

The system will limit access to

authorized users.

·

The spreadsheet can secure data

with electronic signatures.

Security Requirements

·

Members of the Data Entry group

can enter requests but can not approve or delete requests.

·

Members of the Managers group can

enter or approve a request but can not delete requests.

·

Members of the Administrators

group cannot enter or approve requests but can delete requests.

Depending on the system being described, different categories of

requirements are appropriate. System Owners, Key End-Users, Developers,

Engineers, and Quality Assurance should all participate in the requirement

gathering process, as appropriate to the system.

Requirements outlined in the Functional Requirements Specification are

usually tested in the Operational Qualification.

Additional Comments

The Functional Requirements Specification describes what the system must

do; how the system does it is described in the Design Specification.

If a User Requirement Specification was written, all requirements

outlined in the User Requirement Specification should be addressed in the

Functional Requirements Specification.

The Functional Requirements Specification should be signed by the System

Owner and Quality Assurance. If key end-users, developers, or engineers were

involved with developing the requirements, it may be appropriate to have them

sign and approve the document as well.

Depending on the size and complexity of the program, the Functional

Requirements Specification document can be combined with either the user

requirements specification or the design specification.

A functional requirement

describes what a software system

should do, while non-functional requirements place constraints on how the system will do so.

The functional requirement is describing

the behavior of the system as it relates to the system's functionality. The

non-functional requirement elaborates a

performance characteristic of

the system.

Functional Requirements

Usability,

Reliability, Performance, and Supportability Requirements

The remaining "URPS" categories describe

non-functional requirements that are generally architecturally significant.

·

Usability is concerned with characteristics

such as aesthetics and consistency in the

user interface.

·

Reliability is concerned with characteristics

such as availability (the amount of system

"up time"), accuracy of system calculations, and the system's

ability to recover from failure.

·

Performance is concerned with characteristics

such as throughput, response time, recovery

time, start-up time, and shutdown time.

· Supportability is concerned with characteristics such as testability, adaptability, maintainability,

compatibility, configurability, installability, scalability, and

localizability.

Design,

Implementation, Interface, and Physical Requirements

The "+" in the FURPS+ acronym is used to

identify additional categories that generally represent constraints.

·

A design requirement, often called a design constraint, specifies or

constrains the options for designing a system. For example, if you specify that

a relational database is required, that's a design constraint.

·

An implementation requirement specifies or constrains the coding or

construction of a system. Examples might include required standards,

implementation languages, and resource limits.

·

An interface requirement specifies an external item with which a

system must interact, or constraints on formats or other factors used within

such an interaction.

·

A physical requirement specifies a physical constraint imposed on the

hardware used to house the system — shape, size, or weight, for example.

An

Approach for Gathering Architectural Requirements

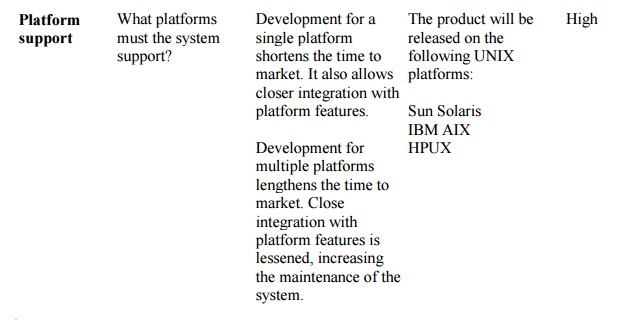

The approach to gathering architectural requirements

we will explore is simple:

1.

Maintain a complete list of

architectural requirements (regardless of whether all items are relevant to a

particular projectFor each architectural requirement, formulate one or more

questions that can help in the specification process. Make sure all the system's stakeholders can

understand these questions.

2.

Assist stakeholders by showing

them the potential impact of answering a question one way or the other.

3.

Capture the responses from your

stakeholders to each of the questions.

4.

Assist the architect by ensuring

that the stakeholders — in addition to answering these questions — assign a

priority or weighting to each architectural requirement. This weighting will

allow the architect to make tradeoffs between requirements.

It is worth noting that this approach is possible

because, at a high level, the set of architectural requirements that must be

considered is finite. You can also apply this approach to requirements

gathering within particular problem domains that also have finite,

well-defined, sets of considerations. For a financial system, for example,

there would be an imperative to pose certain finance-related questions.

The

Architectural Requirements Questionnaire

Related Topics