Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiety Disorders: Social and Specific Phobias

Social and Specific Phobias: Psychosocial Treatments

Psychosocial Treatments

Specific Phobias

Numerous studies have shown that exposure-based treatments are effective

for helping patients to overcome a variety of specificphobias including fears

of blood, injections dentists, spiders, snakes, rats), enclosed places, thunder

and lightning, water, flying, heights, choking and balloons. Furthermore, the

way in which exposure is conducted may make a difference. Exposure-based

treatments can vary on a variety of dimensions including the degree of

therapist involvement, duration and intensity of exposure, frequency and number

of sessions, and the degree to which the feared situation is confronted in

imagination versus in real life. In addition, because individuals with certain

specific phobias often report a fear of panicking in the feared situation,

investigators have suggested that adding various panic manage-ment strategies

(e.g., cognitive restructuring, exposure to feared sensations) may help to

increase the efficacy of behavioral treat-ments for specific phobias. It

remains to be shown whether the addition of these strategies will improve the

efficacy of treat-ments that include only exposure.

Exposure seems to work best when sessions are spaced close together.

Secondly, prolonged exposure seems to be more effective than exposure of

shorter duration. Thirdly, during ex-posure sessions, patients should be

discouraged from engaging in subtle avoidance strategies (e.g., distraction)

and over-reliance on safety signals (e.g., being accompanied by one’s spouse

during ex-posure). Fourth, real-life exposure is more effective than exposure

in imagination. Fifthly, exposure with some degree of therapist involvement

seems to be more effective than exposure that is ex-clusively conducted without

the therapist present. Exposure may be conducted gradually or quickly. Both

approaches seem to work equally well, although patients may be more compliant

with a grad-ual approach. Finally, in the case of blood and injection phobias,

the technique called applied muscle tension should be considered as an

alternative or addition to exposure therapy. Applied muscle tension involves

having patients repeatedly tense their muscles, which leads to a temporary

increase in blood pressure and pre-vents fainting upon exposure to blood or

medical procedures.

Cognitive strategies have also been used either alone or in conjunction

with exposure for treating specific phobias. The evidence suggests that the

addition of cognitive strategies to ex-posure may provide added benefit for

some individuals. For a de-tailed guide to integrating cognitive strategies

with exposure see Antony and Swinson (2000).

Specific phobias are among the most treatable of the anxi-ety disorders.

For example, in as little as one session of guided exposure lasting 2 to 3

hours, the majority of individuals with animal or injection phobias are judged

much improved or com-pletely recovered. A recent study demonstrated that one

session of exposure treatment was effective in the treatment of children and

adolescents with various specific phobias and exposure con-ducted with a parent

present was equally effective as exposure treatment conducted alone. However,

despite how straightfor-ward the concept of exposure may seem, many subtle

clinical issues can lead to problems in implementing exposure-based treatments.

For example, although a patient might be compliant with therapist-assisted exposure

practices, he or she may refuse to attempt exposure practices alone between

sessions. In such cases, involving a spouse or other family member as a coach

dur-ing practices at home may help. In addition, gradually increasing the

distance between therapist and patient during the therapist-assisted exposures

will help the patient to feel comfortable when practicing alone. However, to

maintain the patient’s trust and to maximize the effectiveness of behavioral

interventions, it is im-portant that exposure practices proceed in a

predictable way, so that the patient is not surprised by unexpected events.

Several self-help

books and manuals for treating a range of specific pho-bias have been published

in the past decade. Whereas some of these manuals were developed to be used

with the assistance of a therapist (Bourne, 1998; Antony et al., 1995;

Craske et al., 1997),

others were developed for self-administration (Brown, 1996).

Recent developments in technology have started to have an impact on the

treatment of specific phobias. Videotapes are com-monly used to show feared

stimuli to patients during exposure. Computer administered treatments have also

been used. More recent is the use of virtual reality to expose patients to

simulated situations that are more difficult to replicate in vivo such as flying (Kahan et

al., 2000) and heights (Rothbaum et

al., 1995). Emerg-ing data on the effectiveness of virtual reality is

encouraging. However, other preliminary studies indicate that in vivo exposure is still superior

(Dewis et al., 2001).

Social Phobia

Empirically validated psychosocial interventions for social pho-bia have

primarily come from a cognitive–behavioral perspec-tive and include four main

types of treatment: 1) exposure-based strategies; 2) cognitive therapy; 3)

social skills training; and 4) applied relaxation. Exposure-based treatments

involve repeat-edly approaching fear-provoking situations until they no longer

elicit fear. Through repeated exposure, patients learn that their fearful

predictions do not come true despite their having con-fronted the situation.

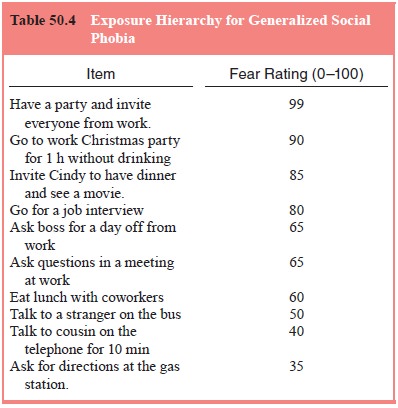

Table 50.4 illustrates an example of an ex-posure hierarchy that might be used

to structure a patient’s expo-sure practices. An exposure hierarchy is a list

of feared situations that are rank ordered by difficulty and used to guide

exposure practices for phobic disorders including social phobia and specific

phobia. The patient and therapist generate a list of situations that the

patient finds anxiety provoking. Items are placed in descend-ing order from

most anxiety provoking to least anxiety provok-ing, and each item is rated with

respect to how anxious the patient might be to practice the item. Exposure

practices are designed to help the patient become more comfortable engaging in

the activi-ties from the hierarchy. Cognitive therapy helps patients identify

and change anxious thoughts (e.g., “Others will think I am stupid

if I participate in a conversation at work”) by teaching them to

consider alternative ways of interpreting situations and to exam-ine the

evidence for their anxious beliefs. Social skills training is designed to help

patients to become more socially competent when they interact with others.

Treatment strategies may include modeling, behavioral rehearsal, corrective

feedback, social rein-forcement and homework assignments. Finally, applied

relaxa-tion involves learning to relax one’s muscles during rest, during

movement and eventually in anxiety-provoking social situations.

Although these methods are presented as four distinct treatment

approaches, there is often overlap among the various treatments. Social skills

training typically requires exposure to the phobic situation so that new skills

may be practiced (e.g., behavioral rehearsal). The same may be said of applied

relaxa-tion, which includes learning to conduct relaxation exercises in the

phobic situation. In fact, most treatments for social phobia involve some type

of exposure to anxiety-provoking social inter-actions and performance-related

tasks. Furthermore, many cog-nitive–behavioral therapists treat patients using

several different strategies delivered in a comprehensive package.

Studies demonstrating the efficacy of CBT for social phobia are too

numerous to describe in detail. Several studies have compared various

cognitive–behavioral strategies and their combinations for treating social

phobia. For example, Wlazlo and colleagues (1990) compared social skills

training to ex-posure therapy conducted either individually or in groups. All

three treatments led to significant improvements and there were no differences

between treatments. However, exposure therapy conducted in groups tended to be

more effective for the subset of patients with social skills deficits, most

likely by enabling those individuals with deficits to develop their skills

through exposure to social situations and interactions in the group. There is

con-flicting evidence that guided exposure is more effective when cognitive

therapy is included than when exposure is conducted without cognitive therapy.

Heimberg and colleagues (1990) compared supportive psy-chotherapy with a

comprehensive CBGT package that included exposure to simulated and real social

situations as well as cogni-tive restructuring for the treatment of social

phobia. Although both groups improved on most measures, patients receiving CBGT

were significantly more improved immediately after treat-ment and at 3- and

6-month follow-up. CBGT was more effective despite that patient ratings of

treatment credibility and expecta-tions for improvement were equal for both

treatments. Patients receiving CBGT continued to be more improved at 5-year

follow-up, although only 41% of the original sample participated in the

follow-up study, which limited the validity of these findings.

Four treatments for social phobia have been compared: 1) CBGT, 2)

phenelzine, 3) supportive psychotherapy, and 4) pla-cebo. Overall, both

phenelzine and CBGT were equally effective after 12 weeks of treatment and were

significantly more effective than placebo or supportive psychotherapy.

Phenelzine tended to work more quickly than CBGT and appeared to be more

effec-tive on a few measures. However, preliminary analyses of long-term outcome

showed that after discontinuing treatment, patients receiving CBGT were more

likely than patients who received phenelzine to maintain their gains, with

approximately half of patients taking phenelzine relapsing, compared with none

of the patients who responded to CBGT.

In a randomized clinical trial comparing cognitive therapy to

moclobemide for social phobia, Oosterbaan and colleagues (2001) found that

cognitive therapy was significantly better than moclobemide, but not placebo,

after 15 weeks of active treatment. After a 2-month follow-up period, cognitive

therapy was signifi-cantly better than both moclobemide and placebo. In

addition, treatment gains in the cognitive therapy group were maintained over a

15-month follow-up period.

Exposure therapy alone or in combination with sertraline for generalized

social phobia in a primary care setting has been studied. Family physicians

(FPs) were trained for 30 hours in assessment of social phobia and in the

application of exposure therapy. FPs reported satisfaction with the training

program and found that the exposure treatment was also useful for treating

pa-tients with other conditions. Although exposure therapy and ser-traline were

effective alone, the combination of exposure therapy and sertraline appeared to

confer added benefit.

According to cognitive models of social phobia, one of the mechanisms by

which CBT works is by causing a positive shift in an individual’s

self-representation (e.g., decreased negative self-focused thoughts and

increased task-focused thoughts and positive self-focused thoughts). Indeed,

there is evidence that fol-lowing CBT, individuals report significantly fewer

negative self-focused thoughts. Similarly, cognitive biases are reduced

follow-ing successful pharmacotherapy treatment as well and are related to the

degree of symptomatic improvement in both psychological and pharmacological

treatments.

In summary, it seems clear that effective psychosocial treatments and

medications for social phobia exist. Although both types of treatments appear

to be equally effective, each has advantages and disadvantages. Medication

treatments may work more quickly and are less time-consuming for the patient

and therapist. In contrast, improvement after CBT appears to last longer. Due

to medication side effects, CBT may be more appropriate for some individuals.

More studies are needed to examine the efficacy of combined medication and

psychoso-cial treatments for social phobia. A meta-analysis of 24 stud-ies

examining cognitive–behavioral and medication treatments for social phobia

found that both treatments were more effec-tive than control conditions (Gould et al., 1997). In this study, the SSRIs

and benzodiazepines tended to have the largest effect sizes among medications

and treatments involving exposure ei-ther alone or with cognitive therapy had

the largest effect sizes among CBT. Another meta-analytic study of 108

psychological and pharmacological treatment-outcome trials found that the

pharmacotherapies (SSRIs, benzodiazepines, MAO inhibitors) were the most

consistently effective treatments, with both SS-RIs and benzodiazepine

treatments equally effective and more effective than control groups (Fedoroff

and Taylor, 2001). Fur-ther, maintenance of treatment gains for CBT was

moderate and continued during follow-up intervals. In comparison, it is not

known the extent to which treatment gains for medication treatments are

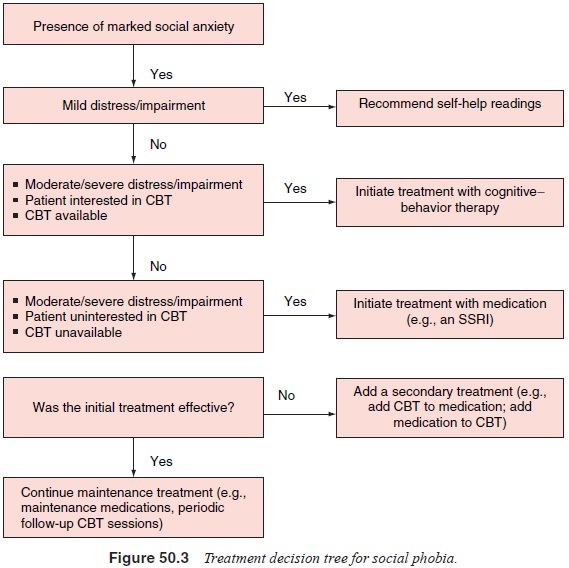

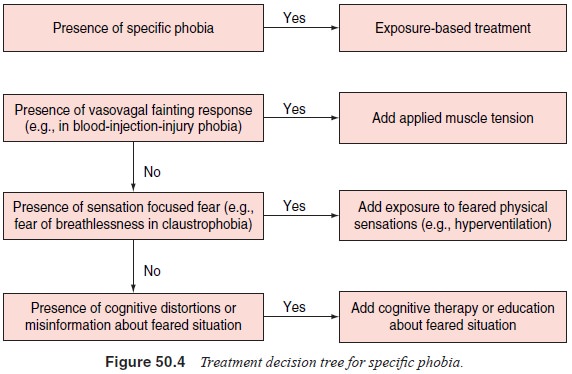

maintained following discontinuation. Treatment decision trees for social and

specific phobias are presented in Figures 50.3 and 50.4.

Related Topics