Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiety Disorders: Social and Specific Phobias

Social and Specific Phobias: Assessment

Assessment

Special Issues in Psychiatric Examination and History

During all parts of the initial evaluation, the psychiatrist should be

sensitive to several issues. First, for many patients with pho-bias, even

discussing the phobic object can provoke anxiety. For example, some patients

with spider phobias experience panic at-tacks when they discuss spiders. Some

patients with blood pho-bias faint when they discuss surgical procedures.

Therefore, the psychiatrist should ask the patient whether discussing the

phobic object or situation will provoke anxiety. If the interview is likely to

be a source of stress, the psychiatrist should emphasize the importance of the

information that is being collected, as well as the potential therapeutic value

of discussing the feared object. As described in a later section, exposure to

the feared stimulus is an essential component of the treatment of most specific

pho-bias. Of course, the interviewer should use his or her judgment when

deciding how much to push the patient in the first session. For treatment to be

effective, establishing trust in the psychiatrist early in the course of

treatment is essential.

With respect to social phobia, the assessment itself may be considered a

phobic stimulus. Because individuals with social phobia fear the evaluation of

others, a psychiatric interview may be especially frightening. Even completing

self-report question-naires in the waiting room may be difficult for patients

who fear writing in front of others. The psychiatrist should be sensitive to

this possibility and provide reassurance when appropriate.

Structured and Semistructured Interviews

Although there are numerous structured and semistructured in-terviews

available, two of the most commonly used interviews for diagnosing anxiety

disorders are the Anxiety Disorders In-terview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV)

(Brown et al., 1994) and the

Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV-TR Disorders-Patient Edition

(SCID-I/P for DSM-IV-TR) (First et al.,

2001). Current and lifetime diagnoses of specific phobia and social phobia based on the ADIS-IV have been shown to have

good to excellent reliability for the specific phobia types and the generalized

type of social phobia. Each interview has advantages and disadvantages.

Although the SCID-I provides detailed assessment of a broader range of

disorders relative to the ADIS-IV (including eating disorders and psychotic

disor-ders), the ADIS-IV provides more detailed information on each of the

anxiety disorders and, like the SCID-I, includes sections to provide DSM-IV

diagnoses for the mood disorders and other disorders that are typically

associated with the anxiety disorders (e.g., substance use and somatoform

disorders). In addition, the ADIS-IV includes more questions to help

differentiate specific and social phobias from other disorders with which they

share features.

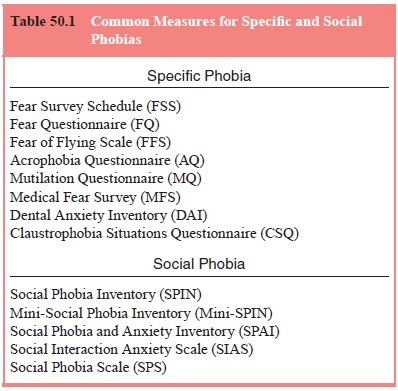

Self-report Measures

Numerous self-report measures have been created for the assess-ment of

specific phobias and social anxiety. The main advantage of self-report measures

is the time that they save for the psychia-trist. Relevant self-report measures

are recommended before the clinical interview if possible. This will allow the

interviewer to follow up specific responses during the interview. Measures can

be administered again, periodically, to assess progress and out-come. It should

be noted that questionnaire measures do not al-ways correlate highly with

performance on behavioral measures. Furthermore, there is evidence that men are

more likely than women to underestimate their fear on specific phobia measures.

The most common questionnaires used to screen for specific phobias are the

various versions of the Fear Survey Schedule. In addition, a variety of

measures exist to assess fear of specific objects and situations. For example,

the Mutilation Question-naire (Klorman et

al., 1974) is among the most common tests for assessing fear of situations

involving blood and medical pro-cedures. Self-report measures for assessing

both specific phobia and social anxiety are listed in Table 50.1.

Behavioral Tests

Behavioral testing is an important part of any comprehensive evaluation for a phobic disorder. This is particularly the case if behavioral or cognitive–behavioral treatment will be used. Because most individuals with phobias avoid the objects and situations that they fear, patients may find it difficult to describe the subtle cues that affect their fear in the situation. In addition, it is not unusual for patients to misjudge the amount of fear that they typically experience in the phobic situation. A behavioral approach test can be useful for identifying specific fear triggers as well as for assessing the intensity of the patient’s fear in the actual situation.

To conduct a behavioral approach test, patients should be instructed to

enter the phobic situation for several minutes. For example, an individual with

a snake phobia should be instructed to stand as close as possible to a live

snake and note the specific cues that affect the fear (e.g., size of snake,

color, movement) and the intensity of the fear (perhaps rating it on a

0–100-point scale). Patients should pay special attention to their physical

sensations (e.g., palpitations, sweating, blushing), negative thoughts (e.g.,

“I will fall from this balcony”) and anxious coping strategies (e.g., escape,

avoidance, distraction).

The behavioral approach test will help in the develop-ment of a specific

treatment plan. However, before treatment patients will often be reluctant to

enter the feared situation. If this is the case, the information collected

during the behavioral approach test may be elicited during the early part of

behavioral treatment.

Differences in Sex, Cultural and Developmental Presentation

Sex Differences

As mentioned earlier, specific phobias tend to be more common among

women than men. This finding seems to be strongest for phobias from the animal

type, whereas sex differences are smaller for height phobias and

blood-injury-injection phobias. In addition, social phobia tends to be slightly

more prevalent among women than men, although these differences are rela-tively

small.

There are several reasons why women may be more likely than men to

report specific phobias. First, men tend to underreport their fear. Also, women

may be more likely than men to seek treatment for their difficulties, which

would account for the fact that sex differences are often larger in treatment

samples compared with epidemiological samples. In addition sex ratios for

phobias differ across cultures, which may be explained by cultural differences

in treatment seeking. Finally, the sex differ-ence in prevalence may reflect

actual differences between men and women in susceptibility to develop phobias.

Women and men are taught to deal differently with typi-cal phobic

stimuli. Traditionally, boys more than girls are often encouraged to play with

spiders and toy snakes and to engage in more adventurous activities (e.g.,

hiking in high places). In ad-dition, women may have more role models for the

development of fear than do men. Images of women standing on chairs when they

see a mouse or running away from spiders are common in children’s cartoons and

other media, but men are rarely depicted as being frightened by these objects.

Therefore, it is possible that in Western cultures women learn to fear certain

situations more strongly than do men. Of course, it is difficult to know

whether culture and the media are responsible for sex differences or sim-ply

reflect differences that exist for other reasons (e.g., different predisposing

factors). It will be interesting to see whether sex ratios for phobias change

as traditional gender roles continue to change

Cultural Differences

Little is known about cultural differences in specific and social

phobias. Nevertheless, a few studies bear on the issue of cultural differences

in phobias. For example, there is evidence from epi-demiological studies that

African-Americans are 1.5 to 3 times as likely as whites to report phobic

disorders, even after controlling for education and socioeconomic status.

Several explanations for this finding have been provided. For example, some of

the fears reported by African-American individuals may reflect realistic

concerns that were misdiagnosed as phobias. For example, Afri-can-American

persons in inner city communities may have more realistic reasons to fear

violence. Furthermore, African-Ameri-cans experience more negative evaluation

from others, and some of their social concerns may be realistic. Another

possibility is that African-Americans experience more chronic stress than

whites and therefore may be more susceptible to the development of phobias and

other problems. Finally, there may be cultural dif-ferences in response biases

on questionnaire measures of fear and during interviews.

Research

has found that specific phobias, but not social phobias, are more common among

US-born Mexican-Americans than in US-born whites or immigrant

Mexican-Americans, after controlling for sex, age, socioeconomic status and

various other variables. A variety of studies have shown that specific phobias,

social phobia and related conditions exist across cultures. For ex-ample, in

Japan, a condition exists called taijin kyôfu in which in-dividuals have an “obsession of

shame”. This condition has much overlap with social phobia in that it is often

accompanied by fears of blushing, having improper facial expressions in the

presence of others, looking at others, shaking and perspiring in front of

others. In addition, studies have identified individuals with so-cial and

specific phobias in a variety of other nonWestern coun-tries including Saudi

Arabia, India, Japan and other East Asian countries. Interestingly, in some

other cultures, the sex ratio forphobias

tends to be reversed. For example, in studies from Saudi Arabia and India, up

to 80% of individuals reporting for treat-ment of phobias were male.

Psychiatrists treating patients from different cultures should be aware

of cultural differences in presentation and re-sponse to treatment, such as

cultural differences in verbal com-munication styles, proxemics (i.e., use of

interpersonal space), nonverbal communication and other verbal cues (e.g., tone

and loudness). Many cues that a psychiatrist might use to aid in the diagnosis

of social phobia in white Americans may not be use-ful for diagnosing the

condition in other cultures. For example, although many psychiatrists interpret

a lack of eye contact as indicating shyness or a lack of assertiveness,

avoidance of eye contact among Japanese and Mexican-Americans is often viewed

as a sign of respect. In contrast to white Americans, Japanese are apparently

more likely to view smiling as a sign of embar-rassment or discomfort.

Furthermore, cultural differences in tone and volume of speech may lead

psychiatrists to misinterpret their patients. For example, whereas white

Americans are often un-comfortable with silence in a conversation, British and

Arab in-dividuals may be more likely to use silence for privacy and other

cultures use silence to indicate agreement among the parties or a sign of

respect. In addition, Asian individuals have been reported to speak more

quietly than white Americans, who in turn speak more quietly than those from

Arab countries. Therefore, differ-ences in the volume of speech should not be

taken to imply differ-ences in assertiveness or other indicators of social

anxiety.

Treatment methods may have to be adapted for different cultures. For

example, the direct style of many cognitive and be-havioral therapists may be

more likely to be perceived as rude or insensitive by individuals with certain

cultural backgrounds than those with other backgrounds. It should be noted that

individu-als within a culture differ on these variables just as individuals

across cultures differ. Therefore, although psychiatrists should be aware of

cultural differences, these differences should not blind the psychiatrist to

relevant factors that are unique to each individual patient.

Developmental Differences

Among children, specific and social fears are common. Be-cause these

fears may be transient, DSM-IV-TR has included a provision that social and

specific phobias not be assigned in children unless they are present for more

than 6 months. In addition, children may be less likely than adults to

recognize that their phobia is excessive or unrealistic. The specific ob-jects

feared by children are often similar to those feared by adults, although

children may be more likely to fear objects and situations that are not easily

classified in the four main specific phobia types in DSM-IV-TR (e.g., balloons

or costumed char-acters). In addition, children often report specific and

social phobias having to do with school. Children with social phobia tend to

avoid changing for gym class in front of others, eating in the cafeteria, or

speaking in front of the class. They may stay home sick on days when

frightening situations arise or may make frequent trips to the school nurse.

Whereas some investigators have found that boys and girls are equally likely to

present for treatment of phobias, others have found social phobia to be more

common among girls. In one prospective study of childhood anxiety disorders,

Last and colleagues (1996) found that almost 70% of children with a specific

pho-bia were recovered over a 3- to 4-year period compared with arecovery rate

of 86% for social phobia. Thus, almost a third of the clinical sample with

specific phobia had symptoms that still met clinical criteria for specific

phobia at the end of the follow-up period. This was the lowest recovery rate

among the anxi-ety disorders that were studied. However, those in the clinical

sample with specific phobia had the lowest rate of development of new

psychiatric disorders (15%) compared with the other anxiety disorders studied

(e.g., the rate of development for new psychiatric disorders was 22% for those

in the clinical sample with social phobia).

Related Topics