Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiety Disorders: Social and Specific Phobias

Social and Specific Phobias: Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Panic disorder with agoraphobia may easily be misdiagnosed as social

phobia or a specific phobia (especially the situational type). For example,

many patients with panic disorder avoid a variety of social situations because

of anxiety about having oth-ers notice their symptoms. In addition, some

individuals with panic disorder may avoid circumscribed situations, such as

fly-ing, despite reporting no other significant avoidance. Four vari-ables

should be considered in making the differential diagnosis: 1) type and number

of panic attacks; 2) focus of apprehension; 3) number of situations avoided;

and 4) level of intercurrent anxiety.

Patients with panic disorder experience unexpected panic attacks and

heightened anxiety outside of the phobic situation, whereas those with specific

and social phobias typically do not. In addition, individuals with panic

disorder are more likely than those with specific and social phobias to report

fear and avoid-ance of a broad range of situations typically associated with

agoraphobia (e.g., flying, enclosed places, crowds, being alone, shopping

malls). Finally, patients with panic disorder are typi-cally concerned only

about the possibility of panicking in the phobic situation or about the

consequences of panicking (e.g., be-ing embarrassed by one’s panic symptoms).

In contrast, individu-als with specific and social phobias are usually

concerned about other aspects of the situation as well (e.g., being hit by

another driver, saying something foolish).

Consider two examples in which the differential diagnosis with panic

disorder might be especially difficult. First, individu-als with claustrophobia

are typically extremely concerned about being unable to escape from the phobic

situation as well as being unable to breathe in the situation. Therefore, like

patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia, they usually report heightened

anxiety about the possibility of panicking. The main variable to consider in

such a case is the presence of panic attacks outside of claustrophobic

situations. If panic attacks occur exclusively in enclosed places, a diagnosis

of specific phobia might best de-scribe the problem. In contrast, if the

patient has unexpected or uncued panic attacks as well, a diagnosis of panic

disorder might be more appropriate.

A second example is a patient who avoids a broad range of situations

including shopping malls, supermarkets, walking on busy streets, and various

social situations including parties, meetings and public speaking. Without more

information, this patient’s problem might appear to meet criteria for social

pho-bia, panic disorder with agoraphobia, or both diagnoses. As men-tioned

earlier, patients with panic disorder often avoid social situ-ations because of

anxiety about panicking in public. In addition, patients with social phobia

might avoid situations that are typi-cally avoided by individuals with

agoraphobia for fear of seeing someone that they know or of being observed by

strangers. To make the diagnosis in this case, it is necessary to assess the

rea-sons for avoidance.

Other diagnoses that should be considered before a diag-nosis of

specific phobia is assigned include post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (if

the fear follows a life-threatening trauma and is accompanied by other PTSD

symptoms such as reexperiencing the trauma), obsessive–compulsive disorder (if

the fear is related to an obsession, e.g., contamination), hypochondriasis (if

the fear is related to a belief that he or she has some serious illness),

separation-anxiety disorder (if the fear is of situations that might lead to

separation from the family, for example, traveling on an airplane without one’s

parents), eating disorders (if the fear is of eating certain foods but not

related to a fear of choking) and psy-chotic disorders (if the fear is related

to a delusion).

Social phobia should not be diagnosed if the fear is related entirely to

another disorder. For example, if an individual with obsessive–compulsive

disorder avoids social situations only be-cause of the embarrassment of having

others notice her or his excessive hand washing, a diagnosis of social phobia

would not be given. Furthermore, individuals with depression, schizoid

personality disorder, or a pervasive developmental disorder may avoid social

situations because of a lack of interest in spending time with others. To be

considered social phobia, an individual must avoid these situations

specifically because of anxiety about being evaluated negatively.

In the case of generalized social phobia, the diagnosis of avoidant

personality disorder should be considered as well. Indi-viduals with avoidant

personality disorder tend to display more interpersonal sensitivity and have

poorer social skills than social phobic patients without avoidant personality

disorder. Further-more, most studies suggest that the differences between

avoid-ant personality disorder and social phobia are more quantitative than

qualitative and that the former may simply be a more severe form of the latter.

Therefore, most patients who meet criteria for avoidant personality disorder

will meet criteria for social phobia as well.

Finally, social and specific phobias should be distinguished from normal

states of fear and anxiety. Many individuals report mild fears of circumscribed

situations or mild shyness in certain social situations. Others may report

intense fears of public speak-ing or heights but insist that these situations

rarely arise and that they have no interest in being in these situations. For

the crite-ria for a specific or social phobia to be met, the individual must

report significant distress about having the fear or must report significant

impairment in functioning.

A variety of factors should be considered in deciding whether a

patient’s fear exceeds the threshold necessary for a diagnosis of specific or

social phobia. To make the differential diagnosis between normal fears and

clinical phobias, the psy-chiatrist should consider the extent of the

individual’s avoidance, the frequency with which the phobic stimulus is

encountered, and the degree to which the individual is bothered by having the

fear. For example, an individual who fears seeing snakes in the wild but who

lives in the city never encounters snakes, and never even thinks about snakes

would probably not be diagnosed with a specific phobia. In contrast, when an

individual’s fear of snakes leads to avoidance of walking through parks,

camping, swim-ming and watching certain television programs, despite having an

interest in doing these things, a diagnosis of specific phobia would be

appropriate.

Similar factors should be considered in deciding at what point normal

shyness reaches an intensity that warrants a diag-nosis of social phobia. An

individual who is somewhat quiet in groups or when meeting new people but does

not avoid these situ-ations and is not especially distressed by his or her

shyness would probably not receive a diagnosis of social phobia. In contrast,

an individual who frequently refuses invitations to socialize because of

anxiety, quits a job because of anxiety about having to talk to customers, or

is distressed about her or his social anxiety would be likely to receive a

diagnosis of social phobia.

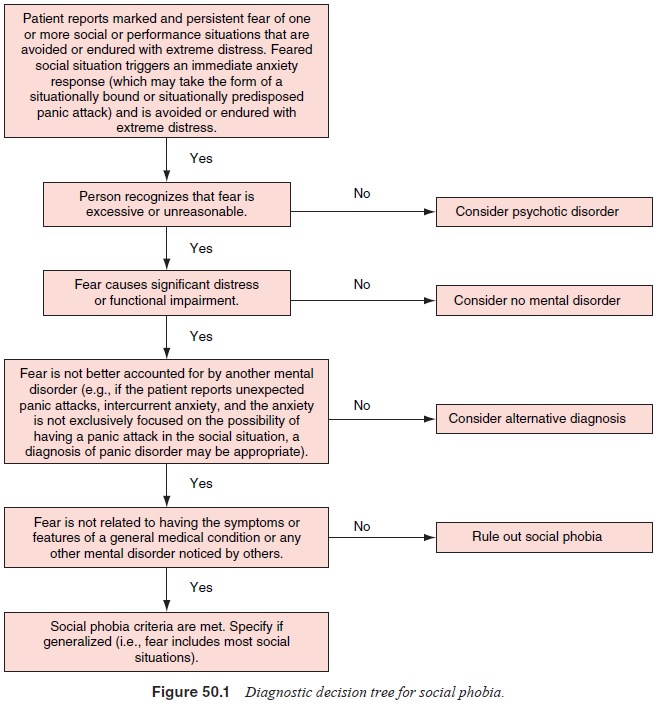

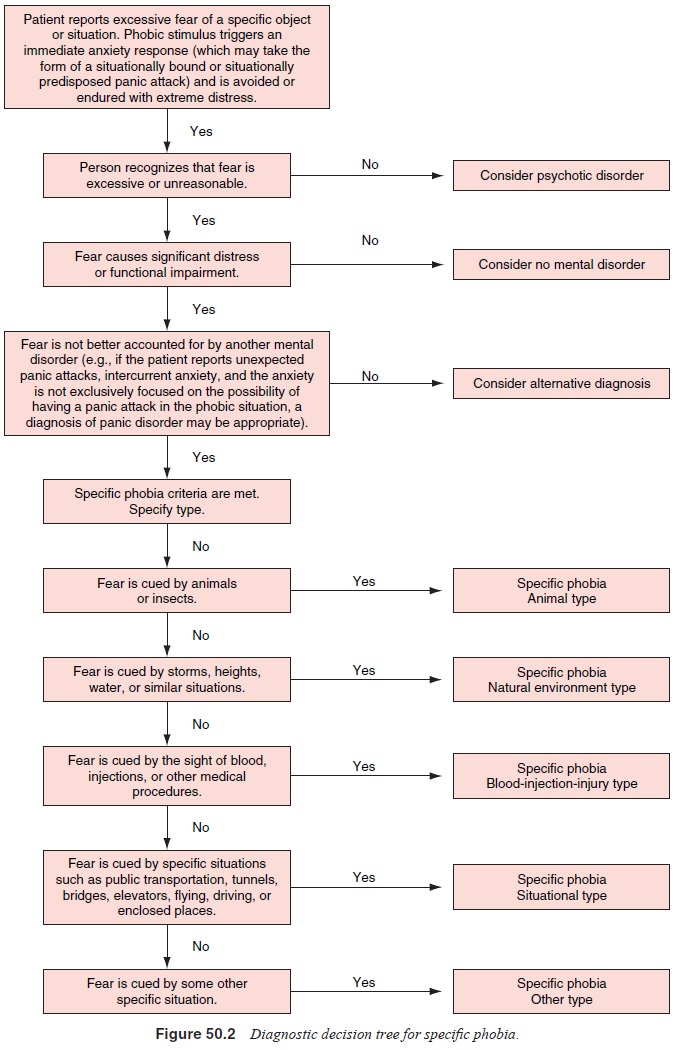

Diagnostic decision trees for social and specific phobias are presented

in Figures 50.1 and 50.2.

Related Topics