Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Bone and Joint Infections

Septic Arthritis

SEPTIC ARTHRITIS

The usual clinical features of septic arthritis include onset of pain, which is often abrupt and accompanied by fever. Single or multiple joints may be involved. Tenderness and swelling of the affected joints and frequently other signs of local inflammation are pres-ent. Attempts to move the joints, either actively or passively, result in severe pain. In in-fants, the symptoms may be somewhat nonspecific; local swelling or excessive irritability with unwillingness to move the affected extremity (pseudoparalysis) may be the only clues to the diagnosis.

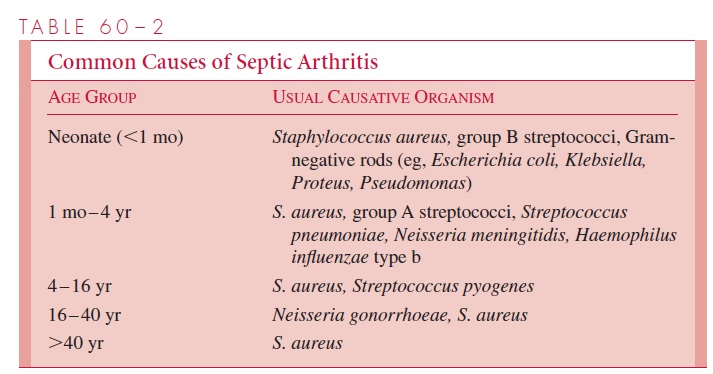

Common Etiologic Agents

The major causes of septic arthritis are listed in Table 60 – 2. Although S. aureus infection can occur at any age, there are some significant age-specific relationships to other bacter-ial causes. There is a high frequency of group B streptococcal infections in neonates, whereas in children between 1 month and 4 years of age, pneumococci are more likely to be involved. Haemophilus influenzae type b disease, which was once quite common in this age group, has been markedly diminished in the last decade; this is believed to be due to widespread use of an effective vaccine. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is implicated in most cases of septic arthritis in young adults. Subacute or chronic infective arthritis should prompt consideration of tuberculosis, Lyme disease, syphilis, and fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis or Candida. Arthritis attributable to Candida is particularly likely in immunocompromised patients.

Viruses and Mycoplasma can also cause acute arthritis in single or multiple joints. Such illnesses have been associated with rubella, hepatitis B, mumps, parvovirus B19, varicella, Epstein – Barr virus, coxsackievirus, and adenovirus infections, as well as with M. pneumoniae and M. hominis. These arthritides are usually self-limiting and rarelyrequire specific therapy. Some bacterial infections of sites other than joints may be associated with noninfectious (reactive) arthritis, possibly resulting from deposition of circulating immune complexes and complement in synovial tissues, leading to inflamma-tion. This has occurred with intestinal infections caused by Yersinia enterocolitica,Campylobacter jejuni, and some Salmonella species and also as a delayed sequela aftersuccessful treatment of sepsis due to N. meningitidis or H. influenzae.

Noninfectious causes of arthritis must also be considered in the differential diagno-sis. They can closely mimic septic arthritis. Examples include inflammatory collagen vascular disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout, traumatic arthritis, and degenerative arthritis.

Diagnostic Approaches

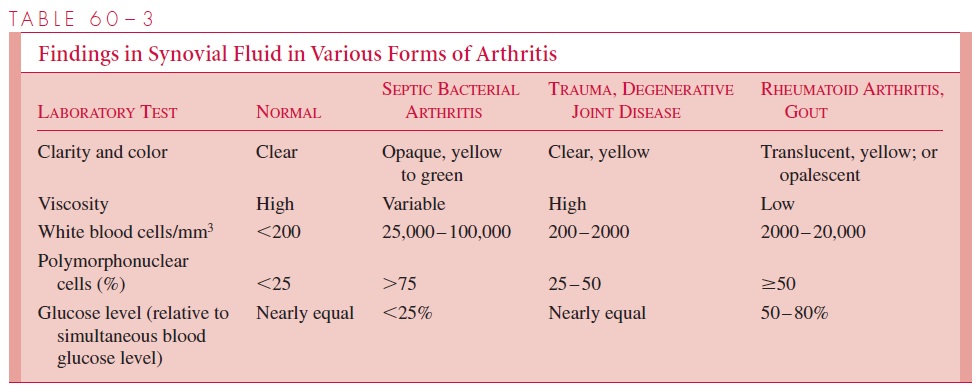

In acute cases, blood cultures are often useful because bacteremia may be present. The definitive diagnosis is established by examination of synovial fluid removed from the joint by needle aspiration (arthrocentesis). Because other noninfectious causes must be considered, it is important to analyze the chemical and cellular characteristics of the fluid in addition to performing a Gram stain and culture. Table 60 – 3 summarizes the major findings in synovial fluid in normal and various disease states. Septic bacterial arthritis is usually associated with grossly purulent fluid containing more than 25,000 white blood cells per cubic millimeter, predominantly polymorphonuclear cells. The glucose level in the synovial fluid is usually less than 25% of that in the blood.

In viral, tuberculous, and fungal arthritis, as well as in partially treated bacterial arthritis, cell counts are usually lower, and mononuclear cells may constitute a greater proportion of the inflammatory cells. Occasionally, biopsy of the synovial membrane may be required to resolve the diagnosis. Histologic examination and culture of the tissue are particularly helpful in distinguishing granulomatous from rheumatoid disease.

In most cases of acute septic arthritis, the blood culture and/or synovial fluid culture yields the specific etiologic agent. One major exception is N. gonorrhoeae, which can be difficult to isolate from these sources. When this organism is suspected, it is wise to in-clude cultures of other sites of potential infection, such as the urethra, cervix, rectum, and pharynx, as well as skin lesions.

Management Principles

Prompt, vigorous, systemic antimicrobial therapy is required as soon as diagnostic tests suggest a bacterial cause. This treatment usually must be continued for 3 to 6 weeks, de-pending on the etiologic agent and the clinical response to therapy. Drainage of pus under pressure is also an important aspect of management. In cases of hip joint involve-ment, open surgical drainage is often necessary because collateral blood supply to the hip joint is relatively limited, and pus under pressure can lead to irreversible avascular necro-sis of the tissues with permanent crippling. It is also difficult to evaluate the amount of pus that may be present because of the overlying muscles. Other joints can usually be managed by simple aspiration of pus whenever it reaccumulates significantly during the acute phase of infection.

Related Topics