Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Eye, Ear, and Sinus Infections

Eye Infections

EYE INFECTIONS

Ocular infections can be divided into those that primarily involve the external structures — eyelids, conjunctiva, sclera, and cornea — and those that involve internal sites. The major de-fense mechanisms of the eye are the tears and the conjunctiva, as well as the mechanical cleansing that occurs with blinking of the eyelids. The tears contain secretory IgA and lysozyme, and the conjunctiva possesses numerous lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and mast cells, which can respond quickly to infection by inflammation and production of an-tibody and cytokines. The internal eye is protected from external invasion primarily by the physical barrier imposed by the sclera and cornea. If these are breached (eg, by a penetrating injury or ulceration), infection becomes a possibility. In addition, infection may reach the in-ternal eye via the blood-borne route to the retinal arteries and produce chorioretinitis and/or uveitis. Such infections are a particularly common problem in immunocompromised patients.

Other causes of inflammation of the external or internal eye can involve autoimmune or allergic mechanisms, which may be provoked by infectious agents or diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

COMMON CLINICAL CONDITIONS

Blepharitis is an acute or chronic inflammatory disease of the eyelid margin. It can takethe form of a localized inflammation in the external margin (hordeolum or stye) or a granulomatous reaction to infection and plugging of a sebaceous gland of the eyelid (chalazion).

Dacryocystitis is an inflammation of the lacrimal sac. It usually results from partial

or complete obstruction within the sac or nasolacrimal duct, where bacteria may be

trapped and initiate either an acute or a chronic infection.

Conjunctivitis is a term used to describe inflammation of the conjunctiva; it may

extend to involve the eyelids, cornea (keratitis), or sclera (episcleritis). Extensive disease involving the conjunctiva and cornea is often called keratoconjunctivitis. Progressive keratitis can lead to ulceration, scarring, and blindness. Ophthalmia neonatorum is an acute, sometimes severe, conjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis of newborn infants.

Endophthalmitis is rare, but often leads to blindness even when treated aggressively.The term refers to infection of the aqueous or vitreous humor, usually by bacteria or fungi.

Uveitis consists of inflammation of the uveal tract — iris, ciliary body, and choroid.Although most inflammations of the iris and ciliary body (iridocyclitis) are not of infec-tious origin, some agents have been implicated. The acute disease may be associated with severe eye pain, redness, and photophobia; other cases may progress quite silently, with decreased visual acuity as the only symptom in the late stages. The most common infec-tive involvement of the uveal tract is chorioretinitis, in which inflammatory infiltrates are seen in the retina; this infection can lead to destruction of the choroid and inflammation of the optic nerve (optic neuritis) and may extend into the vitreous humor to cause en-dophthalmitis. If the disease is not treated adequately, the end result can be blindness.

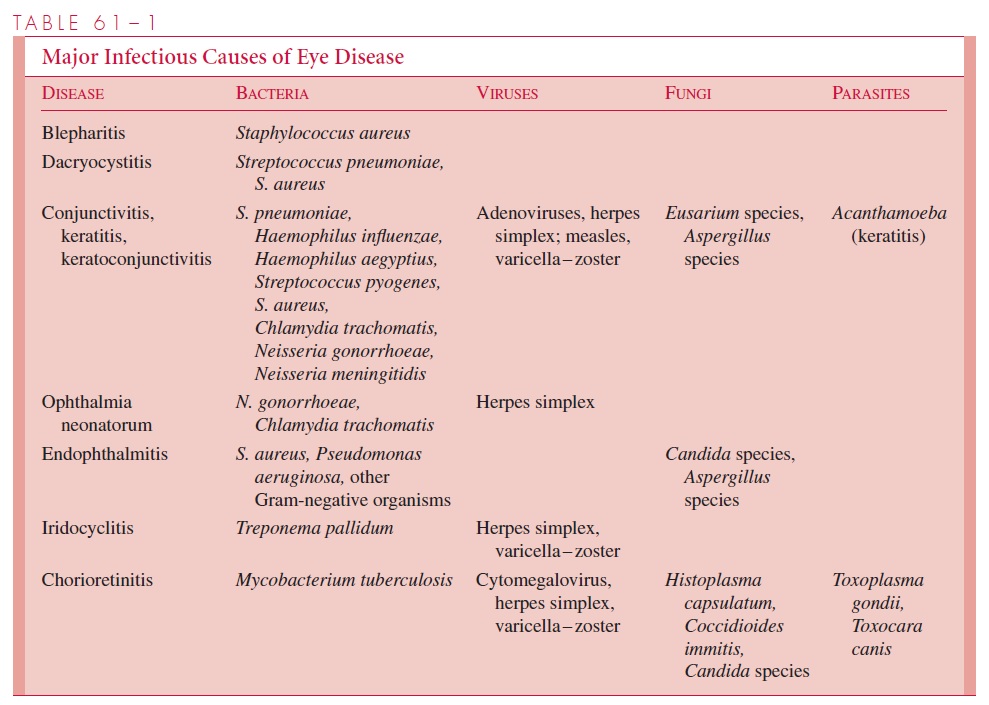

COMMON ETIOLOGIC AGENTS

The major infectious causes of various inflammatory diseases of the eye are listed in Table 61 – 1. Staphylococcus aureus is the principal offender in bacterial infections of the eyelid and cornea. Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae are common causes of acute bacterial conjunctivitis. In young infants, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are significant causes of external eye disease, contracted from themother’s birth canal, that must be diagnosed and treated promptly. Chronic conjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis at any age must also prompt consideration of C. trachomatis infec-tion. Herpes simplex is also a major cause of chronic or recurrent conjunctivitis, espe-cially in infections of the external structures, and specific therapy is available. Epidemic conjunctivitis or keratoconjunctivitis is most commonly associated with a variety of ade-novirus serotypes.

Outbreaks have been associated with inadequately chlorinated swim-ming pools, contaminated equipment or eyedrops in physicians’ offices, and communal sharing of towels, which facilitates direct transmission.

Chorioretinitis is frequently a manifestation of systemic disease (eg, histoplasmosis, tuberculosis) and congenital infections. It is particularly common in immunocompromised patients, who are liable to develop disseminated Candida, cytomegalovirus, or Toxoplasmagondii infections. Endophthalmitis may also result from blood-borne dissemination or bycontiguous spread as a result of injury (eg, corneal ulcerations). In the latter situation, iat-rogenic infection by agents such as Pseudomonasspecies can be induced by contaminated eye drops and ophthalmologic examination equipment.

Infection of the soft tissues surrounding the eye (periorbital or orbital cellulitis) is po-tentially severe and can spread to involve the functions of the eye itself. Major causes are S. aureus, H. influenzae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and S. pneumoniae.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACHES

In external bacterial infections of the eye, etiologic diagnoses can usually be established by Gram stain and culture of surface material or, in the case of viral infections, by tissue culture. Conjunctival scrapings for C. trachomatis can be prepared for immunofluorescent or cytologic examination and for appropriate culture. Infections of internal sites pose a more difficult problem. Some, such as acute endophthalmitis, may require removal of in-fected aqueous humor for microbiologic studies. Infections involving the uveal tract may require indirect methods of diagnosis, such as serologic tests for toxoplasmosis and deep mycoses, blood cultures to demonstrate evidence of disseminated disease (eg, Candida sepsis), and efforts to demonstrate infection in other sites (eg, chest radiography and spu-tum culture to diagnose tuberculosis). Careful ophthalmologic examination using slit lamps and retinoscopy often helps suggest specific etiologic agents based on the morphol-ogy of the lesions observed.

MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES

Various topical antimicrobial agents have been used effectively in external eye infections of presumed or proved bacterial origin. In addition, topical antiviral treatment is available for herpes simplex infections but has not been proved efficacious for other viral diseases of the eye. Severe infections, whether external or internal, require specialized treatment that nearly always includes ophthalmologic consultation because they may threaten vi-sion. Systemic infection associated with eye disease (eg, fungemia, tuberculosis) must be treated vigorously with appropriate antimicrobial agents.

Related Topics