Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Bone and Joint Infections

Osteomyelitis

OSTEOMYELITIS

The onset of acute hematogenous osteomyelitis is usually abrupt but can sometimes be quite insidious. It is classically characterized by localized pain, fever, and tenderness to palpation over the affected site. More than one bone or joint may be involved as a result of hematogenous spread to multiple sites. With progression, the classic signs of heat, redness, and swelling may develop. Laboratory findings often include leukocytosis and elevated acute-phase reactants, such as C-reactive protein and sedimentation rate. Osteomyelitis caused by a contiguous focus of infection is usually associated with the presence of local findings of soft tissue infection, such as skin abscesses and infected wounds.

When osteomyelitis occurs in close proximity to a joint, septic arthritis may develop by direct spread through the epiphysis (usually in infants) or by lateral extension through the periosteum into the joint capsule. Such extension is particularly common in hip and elbow infections.

Common Etiologic Agents

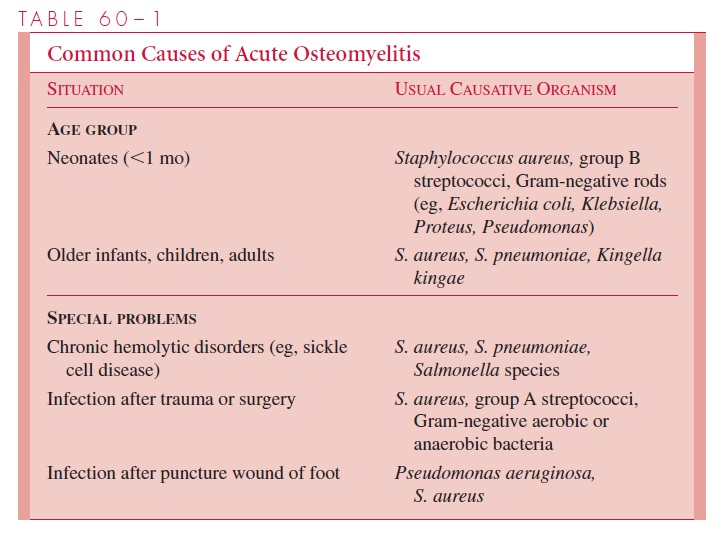

The most common causes of acute osteomyelitis and those associated with special circumstances are shown in Table 60 – 1. It is clear that age plays a significant role in influencing the relative frequency of the various infective agents, particularly in early in-fancy; however, most infections are caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

Low-grade smoldering infections may also occur with the organisms listed in Table 60 – 1; however, chronic granulomatous processes must also be considered, including tu-berculosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, and blastomycosis. These latter infec-tions usually result from systemic dissemination, and the lesions develop slowly over a period of months. Occasionally bone tumors or cysts and leukemia must also be consid-ered in the differential diagnosis.

Diagnostic Approaches

The primary goals of diagnosis are to establish the existence of infection and to determine its cause. The following procedures are generally used:

1. Blood cultures, because many infections are associated with bacteremia.

2. Radionuclide scanning or magnetic resonance imaging to demonstrate evidence of lo- calized infection.

3. Direct staining, culture, and histology of needle aspirates or biopsies of periosteum or bone.

4. X-rays of affected sites, which often appear normal in the early stages of infection. The first changes seen are swelling of surrounding soft tissues, followed by periosteal elevation. Demineralization of bone may not become apparent for 2 weeks or more after the onset of symptoms; calcification of the periosteum and surrounding soft tis- sues is usually delayed even longer.

Management Principles

In acute infections, early intervention is important. Management includes vigorous use of bactericidal antimicrobics, which must often be continued for several weeks to ensure a bacteriologic cure and prevent progression to chronic osteomyelitis. Surgical drainage is also essential if there is significant pressure from the localized, purulent process. In chronic osteomyelitis, sequestrum formation is frequent and sinuses may develop that drain the bone abscess to the skin surface. The infection is persistent, and treatment becomes extremely difficult. Such patients often require long-term antibiotic treatment (months to years) combined with surgical procedures to drain the abscesses and remove necrotic, infected tissues in an attempt to control infection while preserving the integrity of the affected bone.

Related Topics