Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses

Schizophrenia: Psychopharmacological Treatment

Psychopharmacological Treatment

Background

The seminal work of Delay and Deniker (1952) provided a phar-macological

strategy that would forever change the face of schiz-ophrenia. The

implementation of chlorpromazine became the turning point for

psychopharmacology. Patients who had been institutionalized for years were able

to receive treatment as out-patients and live in community settings. The road

was paved for the deinstitutionalization movement, and scientific

understand-ing of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia burgeoned. The

in-troduction of clozapine started the era of antipsychotic agents be-ing

referred to as either “typical” (conventional

or traditional) or “atypical” (or novel) antipsychotic drugs. If

chlorpromazine started the first revolution in the psychopharmacological

treat-ment of schizophrenia, then clozapine ushered in the second and more

profound revolution whose impact is felt beyond schizo-phrenia and its full

extent is yet to be realized. Moreover, cloza-pine has invigorated the

psychopharmacology of schizophrenia and rekindled one of the most ambitious

searches for new antip-sychotic compounds by the pharmaceutical industry. There

are now five novel antipsychotics in the USA: risperidone, olanzap-ine,

quetiapine, ziprasidone and aripiprazole.

Clozapine and the Novel Antipsychotic Agents

Double–blind, controlled studies demonstrated the superior clin-ical

efficacy of clozapine compared with standard neuroleptics, without the

associated extrapyramidal symptoms. It is clearly superior to traditional

neuroleptics for psychosis. Approximately 50% of patients with chronic and

treatment-resistant schizophre-nia derive a better response from clozapine than

from traditional neuroleptics. Its effect on negative symptoms is somewhat

con-troversial and has started an intense and a passionate debate as to whether

the efficacy of the medication is with primary or secondary negative symptoms

or both (Meltzer, 1989a). There is substantial evidence that clozapine

decreases relapses, improves stability in the community, and diminishes

suicidal behavior. There have also been reports that clozapine may cause a

gradual reduction in preexisting tardive dyskinesia.

Unfortunately,

clozapine is associated with agranulocyto-sis and, because of this risk, it

requires weekly white blood cell testing. Approximately 0.8% of patients taking

clozapine and re-ceiving weekly white blood cell monitoring develop

agranulocy-tosis. Women and the elderly are at higher risk than other groups.

The period of highest risk is the first 6 months of treatment. These data has

led to monitoring of white cell counts less frequently after first 6 months to

every other week if a person has a history of white cell counts the within the

normal range in the preceding 6 months. Current guidelines state that the

medication must be held back if the total white blood cell count is 3000/mm3 or less

or if the absolute polymorphonuclear cell count is 1500/mm3 or less.

Patients who stop clozapine treatment continue to require bloodmonitoring for at least 4 weeks after the last dose according to current

guidelines. Other side effects of clozapine include orthos-tatic hypotension,

tachycardia, sialorrhea, sedation, elevated tem-perature and weight gain.

Furthermore, clozapine can lower the seizure threshold in a dose-dependent

fashion, with a higher risk of seizures seen particularly at doses greater than

600 mg/day.

Clozapine has an affinity for dopamine receptors (D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5), serotonin receptors (5-HT2A, 5-HT 2C, 5-HT6 and 5-HT7), alpha-1- and alpha-2-adrenergic receptors, nicotinic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors and H1 histaminergic receptors. As

clozapine has a relatively shorter half-life, it is usually admin-istered twice

a day.

The superior antipsychotic efficacy of clozapine has in-spired an

abundance of research in the field of modern psychop-harmacology for the

treatment of schizophrenia. Clozapine and the other novel compounds have an

array of biochemical profiles, with affinities to dopaminergic, serotoninergic

and noradrener-gic receptors. Research on the atypical antipsychotic compounds

has led to a greater understanding of the biochemical effects of antipsychotic

agents, leaving the basic dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia insufficient to

explain schizophrenic symptoms. Clozapine shows selectivity for mesolimbic

neurons and does not increase the prolactin level. Binding studies have shown

it to be a relatively weak D1 and D2 antagonist, compared with traditional neuroleptics (Farde et al., 1989). Clozapine shares the

property of higher serotonin 5-HT2A to dopamine D2 blockade ratio reported to impart atypicality. The noradrenergic system

may also have a role in the mechanism of action of clozapine (Breier, 1994).

Clozapine, but not traditional neuroleptics, causes up to fivefold increases in

plasma norepinephrine. Moreover, these increases in norepinephrine correlated

with clinical response.

Risperidone

is a benzisoxazol compound with a high affin-ity for 5-HT2A and D2

receptors and has a high serotonin dopamine receptor antagonism ratio. It has

high affinity for alpha-1-adren-ergic and H1

histaminergic receptors and moderate affinity for alpha-2-adrenergic receptors.

Risperidone is devoid of significant activity against the cholinergic system

and the D1

receptors. The efficacy of this medication is equal to that of other first-line

atypi-cal antipsychotic agents and is well tolerated and can be given once or

twice a day. It is available in a liquid form as well. The most common side

effects reported are drowsiness, orthostatic hypotension, lightheadedness, anxiety,

akathisia, constipation, nausea, nasal congestion, prolactin elevation and

weight gain. At doses above 6 mg/day EPS can become a significant issue. The

risk of tardive dyskinesia at the regular therapeutic doses is low.

Olanzapine, a thienobenzodiazepine compound, has an-tagonistic effects

at dopamine D1 through D5 receptors and sero-tonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C and 5-HT6 receptors. The antiserotonergic activity is more potent than the

antidopaminergic one. It also has affinity for alpha-1-adrenergic, M1 muscarinic acetylcholinergic and

H1 histaminergic receptors. It differs from clozapine by not having high

affinity for the 5-HT7, alpha-2-adrenergic and other cholinergic receptors. It has significant

efficacy against positive and negative symptoms and also improves cognitive

functions. EPS is minimal when used in the therapeutic range with the

ex-ception of mild akathisia. As the compound has a long half-life, it is used

once a day and as it is well tolerated, it can be started at a higher dose or

rapidly titrated to the most effective dose. It is available as a rapidly

disintegrating wafer form, which dis-solves immediately in the mouth, and as an

intramuscular form. The major side effects of olanzapine include significant

weight gain, sedation, dry mouth, nausea, lightheadedness, orthostatichypotension,

dizziness, constipation, headache, akathisia and transient elevation of hepatic

transaminases. The risk of tardive dyskinesia and NMS is low. Though used as a

once-a-day medi-cation, it is often administered twice a day with the average

dose of 15 to 20 mg/day. However, doses higher than 20 mg/day are of-ten used

clinically and are thus being evaluated in clinical trials.

Quetiapine,

a dibenzothiazepine compound has a greater affinity for serotonin 5-HT2 receptors than for dopamine D2

recep-tors; it has considerable activity at dopamine D1, D5, D3, D4,

se-rotonin 5-HT1A, and

alpha-1-, and alpha-2-adrenergic receptors. Unlike clozapine, it lacks affinity

for the muscarinic cholinergic receptors. It is usually administered twice a

day due to a short half-life. Quetiapine is as effective as typical agents and

also appears to improve cognitive function. Among 2035 patients enrolled in

seven controlled studies, quetiapine at all doses used did not have an EPS rate

greater than placebo. This is in contrast to olanzapine, risperi-done and

ziprasidone, where there were dose related effects on EPS levels. The rate of

treatment emergent EPS was very low even in high at-risk populations such as

adolescent, parkinsonian patients with psychosis and geriatric patients. Major

side effects include somnolence, postural hypotension, dizziness, agitation,

dry mouth and weight gain. Akathisia occurs on rare occasions. The package

insert warns about developing lenticular opacity or cataracts and advises

periodic eye examination based on data from animal stud-ies. However, recent

data suggest that this risk may be minimal.

Ziprasidone

has the strongest 5-HT2A receptor

binding rela-tive to D2 binding

amongst the atypical agents currently in use. Interestingly, ziprasidone has

5-HT1A agonist

and 5-HT1D

antago-nist properties with a high affinity for 5-HT1A, 5-HT2C and 5-HT1D receptors. As it does not interact with many other

neurotransmit-ter systems, it does not cause anticholinergic side effects and

pro-duces little orthostatic hypotension and relatively little sedation. Just

like some antidepressants, ziprasidone blocks presynaptic reuptake of serotonin

and norepinephrine. Ziprasidone has a rela-tively short half-life and thus it

should be administered twice a day and along with food for best absorption.

Ziprasidone is not completely dependent on CYP3A4 system for metabolism, thus

inhibitors of the cytochrome system do not significantly change the blood

levels. Ziprasidone at doses between 80 and 160 mg/ day is probably the most

effective agent for treating symptoms of schizophrenia. To assess the cardiac

risk of ziprasidone and other antipsychotic agents a landmark study was

designed to evaluate the cardiac safety of the antipsychotic agents, given at

high doses alone and with a known metabolic inhibitor in a randomized study

involving patients with schizophrenia. This was done to replicate the possible

worst-case scenario (overdose or dangerous combina-tion treatment) in the real

world. All antipsychotic agents studied caused some degree of QTc prolongation,

with the oral form of ha-loperidol associated with the least and thioridazine

with the great-est degree. Major side effects reported with the use of

ziprasidone are somnolence, nausea, insomnia, dyspepsia and prolongation of QTc

interval. Dizziness, weakness, nasal discharge, orthostatic hypotension and

tachycardia occur less commonly.

Ziprasidone should not be used in combination with other drugs that

cause significant prolongation of

the QTc interval. It is also contraindicated for patients with a known history

of signifi-cant QTc prolongation, recent myocardial infarction, or symp-tomatic

heart failure. Ziprasidone has low EPS potential, does not elevate prolactin

levels and causes approximately 1 lb weight gain in short-term studies.

At present, with respect to efficacy, it does not appear that any one of

the novel antipsychotic agents (except clozapine) isbetter

than another one in treating schizophrenia. The randomized controlled trials

suggest that, on average, these antipsychotic agents are each associated with

20% improvement in symptoms. However, clozapine is the only new antipsychotic

agent that is more effective than haloperidol in managing treatment resistant

schizophrenia. Unfortunately, its potential for treatment-emergent

agranulocytosis, seizures and the new warning of myocarditis, precludes its use

as a first line agent for schizophrenia. A major difference amongst the newer antipsychotic

agents is the side effect profile and its effect on the overall quality of life

of the patient.

Acute Treatment

In last few years, the use of novel antipsychotics has surpassed the use

of typical ones in the management of acute phase symptoms of schizophrenia,

except for the use of parenteral and liquid forms of antipsychotics where

typical antipsychotic agents still hold an upper hand. However, this trend will

most likely change once the injectable preparations of the novel antipsychotics

enter the market. The primary goal of acute treatment is the ameliora-tion of

any behavioral disturbances that would put the patient or others at risk of

harm. Acute symptom presentation or relapses are heralded by the recurrence of

positive symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech or

behavior, se-vere negative symptoms or catatonia. Quite frequently, a relapse

is a result of antipsychotic discontinuation, and resumption of an-tipsychotic

treatment aids in the resolution of symptoms. There is a high degree of

variability in response rates among individuals. When treatment is initiated,

improvement in clinical symptoms can be seen over hours, days, or weeks of

treatment.

Studies have shown that although typical neuroleptics are undoubtedly

effective, a significant percentage (between 20 and 40%) of patients show only

a poor or partial response to tradi-tional agents. Furthermore, there is no

convincing evidence that one typical antipsychotic is more efficacious as an

antipsychotic than any other, although a given individual may respond better to

a specific drug. Once an informed choice has been made between using a novel or

typical antipsychotic medication by the patient and the clinician, selection of

a specific antipsychotic agent should be based on efficacy, side-effect

profile, history of prior response (or nonresponse) to a specific agent, or

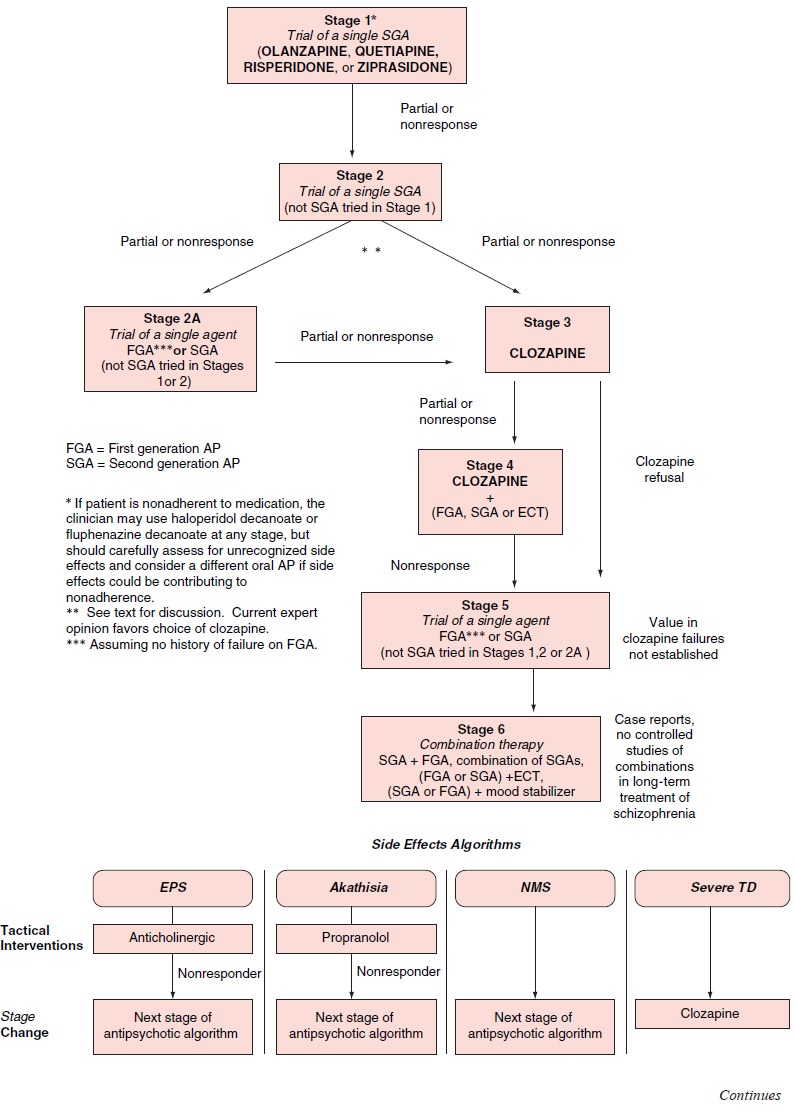

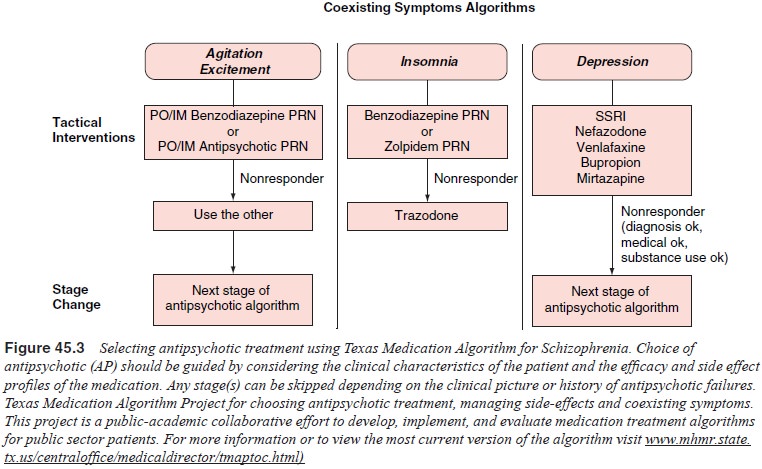

history of response of a family member to a certain antipsychotic agent. (For a

pharmacotherapy decision tree based on Texas Medication Algorithm Project, see

Figure 45.3.) Amongst the typical antipsychotic medications, low-potency, more

sedating agents, such as chlorpromazine, were long thought to be more effective

for agitated patients, yet there are no consistent data proving that high-potency

agents are not equally useful in this context. The low-potency antipsychotics,

however, are more associated with orthostatic hypotension and lowered sei-zure

threshold and are often not as well tolerated at higher doses. Higher potency

neuroleptics, such as haloperidol and fluphena-zine, are safely used at higher

doses and are effective in reducing psychotic agitation and psychosis itself.

However, they are more likely to cause EPS than the low potency agents.

The

efficacy of novel antipsychotic drugs on positive and negative symptoms is

comparable to or even better than the typi-cal antipsychotic. The significantly

low potential to cause EPS or dystonic reaction and thus the decreased

long-term consequences of TD has made the novel agents more tolerable and

acceptable in acute treatment of schizophrenia. Other significant advantages

adding to the popularity of novel antipsychotics include their ben-eficial

impact on mood symptoms, suicidal risk and cognition. The selection of the

first line treatment with novel antipsychotic

(and occasionally typical antipsychotic agent) also depends on the

circumstances under which the medications are started, for example, extremely

agitated or catatonic patients would require intramuscular preparation of the

antipsychotic agents which would limit the choice. Except for clozapine, which

is not con-sidered first line treatment because of substantial and potentially

life threatening side effects, there is no convincing data support-ing the

preference of one atypical over the other. However, if the patient does not

respond to one, a trial with another atypical an-tipsychotic is reasonable and

may produce response.

Once the decision is made to use an antipsychotic agent, an appropriate

dose must be selected. Initially, higher doses or re-peated dosing may be

helpful in preventing grossly psychotic and agitated patients from doing harm.

In general, there is no clear evidence that higher doses of neuroleptics (more

than 2000 mg chlorpromazine equivalents per day) have any advantage over

standard doses (400–600 chlorpromazine equivalents per day).

Some patients who are extremely agitated or aggressive may benefit from

concomitant administration of high-potency benzodiazepines such as lorazepam,

at 1 to 2 mg, until they are stable. Benzodiazepines rapidly decrease anxiety,

calm the person, and help with sedation to break the cycle of agitation. They

also help decrease agitation due to akathisia. The use of these medications

should be limited to the acute stages of the ill-ness to prevent tachyphylaxis

and dependency. Benzodiazepines are quite beneficial in treatment of catatonic

or mute patients but the results are only temporary though of enough duration

to help with body functions and nutrition.

Maintenance Treatment

There is by now a great deal of

evidence from long-term follow-up studies that patients have a higher risk of

relapse and exacerbations if not maintained with adequate antipsychotic

regimens. Noncom-pliance with medication, possibly because of intolerable

neu-roleptic side effects, may contribute to increased relapse rates.

Indouble-blind, placebo-controlled study of relapse rates, 50% of patients in a

research ward demonstrated clinically significant ex-acerbation of their

symptoms within 3 weeks of stopping neurolep-tic treatment. It is estimated

that two-thirds of patients relapse af-ter 9 to 12 months without neuroleptic

medication, compared with 10 to 30% who relapse when typical neuroleptics are

maintained. Long-term outcome studies showed that persistent symptoms that do

not respond to standard neuroleptic therapy are associated with a greater risk

of rehospitalization. Nonpharmacological interven-tions may help decrease

relapse rates (discussed later).

Long-term treatment of schizophrenia is a complex issue. It is clear

that the majority of patients require maintenance medi-cation. Some patients do

well with stable doses of neuroleptics for years without any exacerbations.

However, many patients who are maintained with a stable neuroleptic dose have

episodic breakthroughs of their psychotic symptoms. The difficulty in

tol-erating neuroleptic side effects often results in noncompliance with

medication. It is therefore prudent to assess patients for medication

compliance when signs of relapse are suspected. Pro-dromal cues may be present

before an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms. For example, any recent change in

sleep, attention to activities of daily living, or disorganization may be a

warning sign of an impending increase in psychosis.

For patients for whom compliance is a problem, long-act-ing, depot

neuroleptics are available in the USA for both tradi-tional and novel

antipsychotics. This form of medication deliv-ery guarantees that the

medication is in the system of the person taking it and eliminates the need to

monitor daily compliance. This alternative should be considered if

noncompliance with oral agents has led to relapses and rehospitalization. With

these patients, maintenance treatment using long-acting preparations should begin

as early as possible. Depot antipsychotic drugs are effective maintenance

therapy for patients with schizophrenia.

Many

studies have investigated appropriate maintenance doses of standard

antipsychotics. Effective maintenance treatment is defined as that which

prevents or minimizes the risks of symp-tom exacerbation and subsequent

morbidity. A series of interest-ing dose-finding studies were performed by Kane

and colleagues (1983, 1985) to determine the minimal dosage required to prevent

relapse and to reduce the risk of extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive

dyskinesia. This group found that the relapse rate (56%) of patients treated

with lower doses of fluphenazine decanoate (1.25– 5 mg every 2 weeks) was

significantly greater than the relapse rate (14%) of patients receiving

standard doses (12.5–50 mg every 2 weeks). Other investigators have found that

this low dosage range may appear to prevent relapse for a certain period

(Marder et al., 1984)

but fails to do so if patients are followed up for more than 1 year (Marder et al., 1987).

Unfortunately, no specific dosage reliably prevents relapse, and there is no

way to predict future relapse. This is true for the novel antipsychotic agents

as well.

Related Topics