Chapter: Embedded and Real Time Systems : Process and Operating Systems

Schduling Policies

SCHDULING

POLICIES:

A scheduling

policy defines how processes are selected for promotion from the ready

state to the running state. Every multitasking OS implements some type of

scheduling policy. Choosing the right scheduling policy not only ensures that

the system will meet all its timing requirements, but it also has a profound

influence on the CPU horsepower required to implement the system’s

functionality.

Schedulability

means whether there exists a schedule of execution for the processes in a

system that satisfies all their timing requirements. In general, we must

construct a schedule to show schedulability, but in some cases we can eliminate

some sets of processes as unschedulable using some very simple tests.

Utilization

is one of the key metrics in evaluating a scheduling policy. Our most basic

requirement is that CPU utilization be no more than 100% since we can’t use the

CPU more than 100% of the time.

When we

evaluate the utilization of the CPU, we generally do so over a finite period

that covers all possible combinations of process executions. For periodic

processes, the length of time that must be considered is the hyperperiod,

which is the least-common multiple of the periods of all the processes. (The

complete schedule for the least-common multiple of the periods is sometimes

called the unrolled schedule.) If we evaluate the hyperperiod, we are sure

to have considered all possible combinations of the periodic processes.

We will

see that some types of timing requirements for a set of processes imply that we

cannot utilize 100% of the CPU’s execution time on useful work, even ignoring

context switching overhead.

However,

some scheduling policies can deliver higher CPU utilizations than others, even

for the same timing requirements.

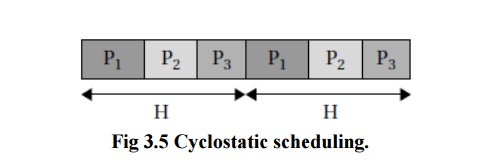

One very

simple scheduling policy is known as cyclostatic scheduling or sometimes

as Time

Division

Multiple Access scheduling. As illustrated in Figure 3.5, a cyclostatic

schedule is divided into equal-sized time slots over an interval equal to the

length of the hyperperiod H.

Processes always run in the same time slot.

Two

factors affect utilization: the number of time slots used and the fraction of

each time slot that is used for useful work. Depending on the deadlines for

some of the processes, we may need to leave some time slots empty. And since

the time slots are of equal size, some short processes may have time left over

in their time slot

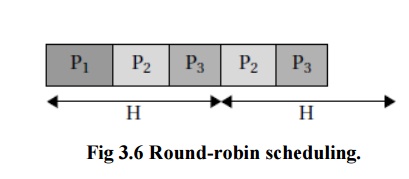

Another

scheduling policy that is slightly more sophisticated is round robin. As

illustrated in Figure 3.6, round robin uses the same hyperperiod as does

cyclostatic. It also evaluates the processes in order.

But

unlike cyclostatic scheduling, if a process does not have any useful work to

do, the round-robin scheduler moves on to the next process in order to fill the

time slot with useful work. In this example, all three processes execute during

the first hyperperiod, but during the second one, P1 has no useful work and is skipped.

The

processes are always evaluated in the same order. The last time slot in the

hyperperiod is left empty; if we have occasional, non-periodic tasks without

deadlines, we can execute them in these empty time slots. Round-robin

scheduling is often used in hardware such as buses because it is very simple to

implement but it provides some amount of flexibility.

In

addition to utilization, we must also consider scheduling overhead—the execution time required to choose the next

execution process, which is incurred in addition to any context switching

overhead.

In

general, the more sophisticated the scheduling policy, the more CPU time it

takes during system operation to implement it. Moreover, we generally achieve

higher theoretical CPU utilization by applying more complex scheduling policies

with higher overheads.

The final

decision on a scheduling policy must take into account both theoretical

utilization and practical scheduling overhead.

Related Topics