Chapter: Pharmaceutical Biotechnology: Fundamentals and Applications : Insulin

Regular and Rapid Acting Soluble Formulations - Pharmacology and Formulations of Insulin

Regular and Rapid-Acting Soluble Formulations

Initial soluble insulin formulations were prepared under acidic

conditions and were chemically unstable. In these early formulations,

considerable deamidation was identified at AsnA21 and significant potency loss was

observed during prolonged storage under acidic conditions. Efforts to improve

the chemical stability of these soluble formulations led to the development of

neutral, zinc-stabilized solutions.

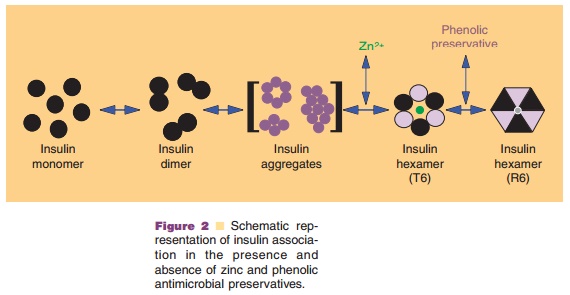

The insulin in these neutral, regular formula-tions is chemically

stabilized by the addition of zinc (~0.4%

relative to the insulin concentration) and phenolic preservatives. As mentioned

above, the addition of zinc leads to the formation of discrete hexameric

structures (containing 2 Zn atoms per hexamer) that can bind six molecules of

phenolic preservatives, e.g., m-cresol (Fig. 2). The binding of these

excipients increases the stability of insulin by inducing the formation of a

specific hexameric conformation (R ), in which the B1 to B8 region of each

monomer is in an α-helical conformation. This in turn decreases the

availabil-ity of residues involved in deamidation and high-molecular-weight

polymer formation (Brange et al., 1992a,b).

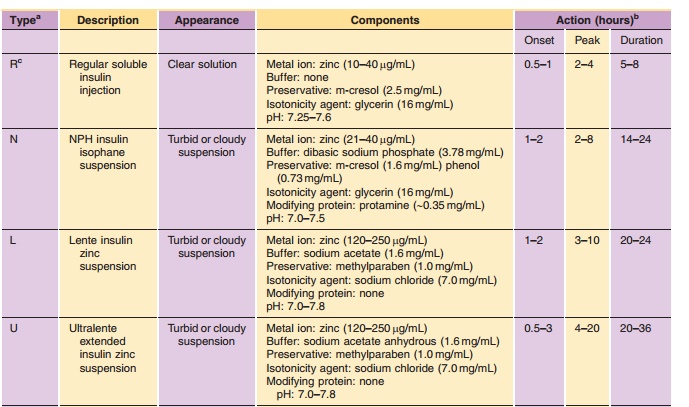

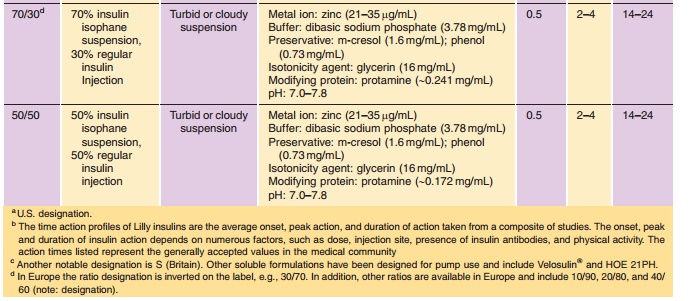

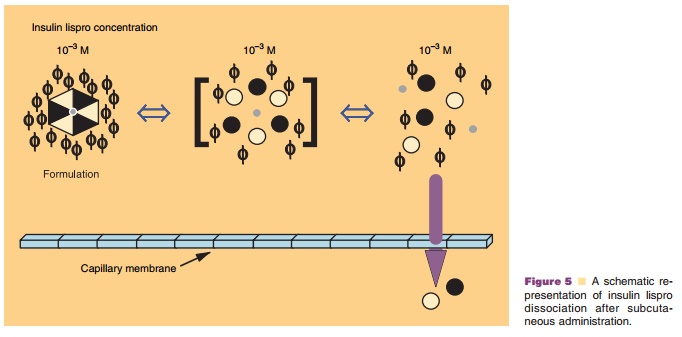

The pharmacodynamic profile of this soluble formulation is listed in Table 2. The neutral, regular formulations show peak insulin activity between 2 and 4 hr with a maximum duration of 5 to 8 hr. As with other formulations, the variations in time-action can be attributed to factors such as dose, site of injection, temperature, and the patient’s physical activity. Despite the soluble state of insulin in these formulations, a delay in activity is still observed. This delay has been attributed to the time required for the hexamer to dissociate into the dimeric and/or monomeric substituents prior to absorption from the interstitium. This dissociation requires the diffu-sion of the preservative and insulin from the site of injection, effectively diluting the protein and shifting the equilibrium from hexamers to dimers and monomers (Fig. 4) (Brange et al., 1990). Recent studies exploring the relationship of molecular weight and cumulative dose recovery of various compounds in the popliteal lymph following sub-cutaneous injection suggest that lymphatic transport may account for approximately 20% of the absorption of insulin from the interstitium (Supersaxo et al., 1990; Porter and Charman, 2000). The remaining balance of insulin is predominately absorbed through capillary diffusion.

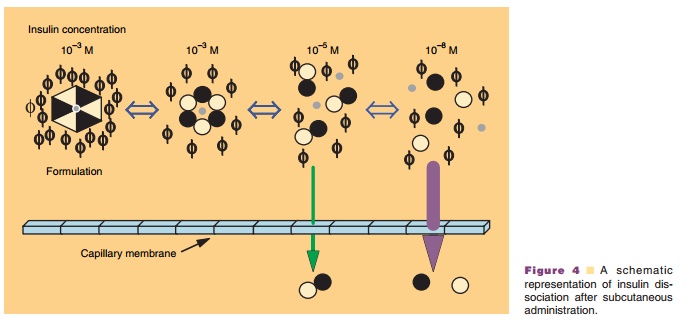

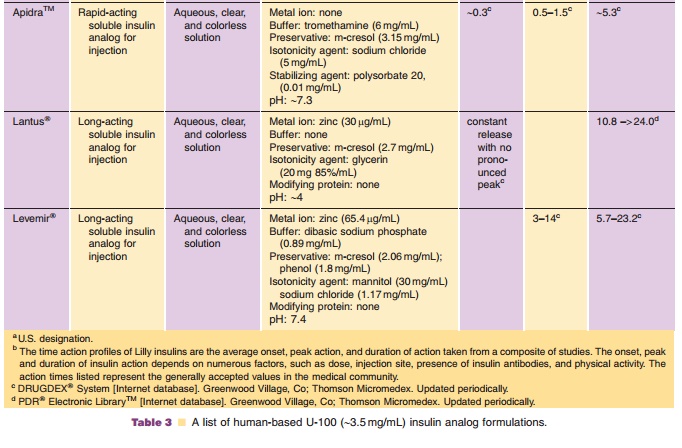

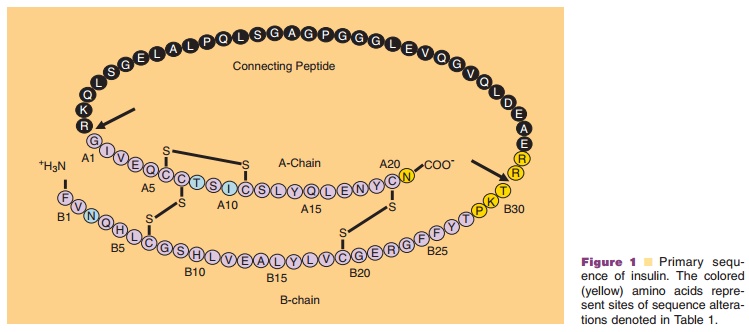

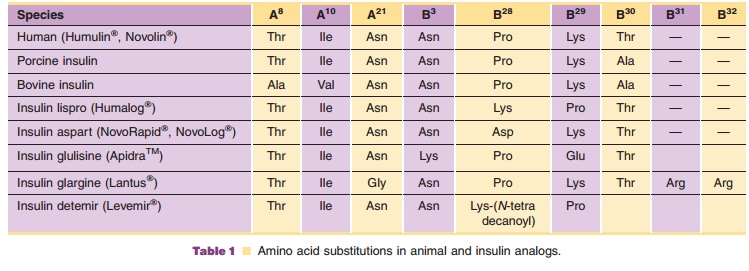

Monomeric insulin analogs were designed to achieve a more natural

response to prandial glucose-level increases while providing convenience to

thepatient. The pharmacodynamic profiles of these soluble formulations are

listed in Table 3. The development of monomeric analogs of insulin for the

treatment of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus has focused on shifting the

self-association properties of insulin to favor the monomeric species and

consequently minimizing the delay in time-action

(Brange et al., 1988, 1990; Brems et al., 1992). One such monomeric

analog, LysB28ProB29-human insulin (Humalog or Liprolog ; insulin lispro; Eli Lilly &

Co., Lilly Corporate Center, Indianapolis, IN) has been developed and does have

a more rapid time-action profile, with a peak activity of approximately 1 hr

(Howey et al., 1994). The sequence inversion at positions B28 and B29 yields an

analog with reduced self-association behavior compared to human insulin (Fig.

1; Table 1); however, insulin lispro can bestabilized in a

preservative-dependent hexameric complex that provides the necessary chemical

and physical stability required by insulin preparations. Despite the hexameric

complexation of this analog, insulin lispro retains its rapid time-action.

Based on the crystal structure of the insulin lispro hexameric complex, Ciszak

et al. (1995) have hypothesized that the reduced dimerization properties of the

analog, coupled with the preservative dependence, yields a hexameric complex

that readily dissociates into

It is important to highlight that the properties engineered into Humalog

not only provide the patient with a more convenient therapy, but also improve

control of postprandial hyperglycemia and reduce the frequency of severe

hypoglycemic events (Anderson et al., 1997; Holleman et al., 1997).

Since the introduction of insulin lispro, two additional rapid-acting

insulin analogs have been introduced to the market. The amino acid

modifications made to the human insulin sequence to produce these analogs are

depicted in Table 1. Like insulin lispro, both analogs are supplied as neutral

pH solutions containing phenolic preservative. The design strategy for

AspB28-human insulin (NovoRapid or NovoLog; insulin aspart; Novo Nordisk A/S,

Corporate Headquarters, Novo Alle´, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) (Brange et al.,

1988, 1990) involves the replacement of ProB28 with a negatively charged aspartic acid residue. Like LysB28ProB29-human insulin, AspB28-human insulin has a more rapid

time-action following subcutaneous injection (Heinemann et al., 1997). This

rapid action is achieved through a reduction in the self-association behavior

compared to human insulin (Brange et al., 1990; Whittingham et al., 1998). The

other rapid-acting analog, LysB3-GluB29-human insulin (ApidraTM, insulin glulisine; Sanofi-Aventis), involves a substitution of the

lysine residue at position 29 of the B-chain with a negatively charged glutamic

acid. Additionally, this analog replaces the AsnB3 with a positively charged

lysine. Scientific reports describing the impact of these changes on the

molecular properties of this analog are lacking. However, the glutamic acid

substitution occurs at a position known to be involved in dimer formation

(Brange et al., 1990) and may result in disruption of key interactions at the

monomer– monomer interface. The Asn residue at position 3 of the B-chain plays

no direct role in insulin self-association (Brange et al., 1990), but it is flanked

by two amino acids involved in the assembly of the Zn2þ insulin hexamer. Despite the

limited physicochemical information on insulin glulisine, studies conducted in

persons with either Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes (Dailey et al., 2004; Dreyer et

al., 2005) confirm the analog displays similar pharmacological properties as

insulin lispro. Interestingly, insulin glulisine is not formulated in the

presence of zinc as are the other rapid-acting analogs. Instead, insulin

glulisine is formulated in the presence of a stabilizing agent (polysorbate 20)

(Table 3). The surfactant in the formulation presumably minimizes higher order

association and contributes to more rapid adsorption of the monomeric species.

In addition to the aforementioned rapid-acting formulations,

manufacturers have designed soluble formulations for use in external or

implanted infusion pumps. In most respects, these formulations are very similar

to Regular insulin (i.e., hexameric association state, preservative, and zinc);

however, buffer and/or surfactants may be included in these formulations to

minimize the physical aggregation of insulin that can lead to clogging of the

infusion sets. In early pump systems, gas-permeable infusion tubing was used

with the external pumps. Consequently a buffer was added to the formulation in

order to minimize pH changes due to dissolved carbon dioxide. Infusion tubing

composed of materials having greater resis-tance to carbon dioxide diffusion is

currently being used and the potential for pH-induced precipitation of insulin

is greatly reduced. All three of the commercially available rapid-acting

insulin analogs are approved for use in external infusion pumps.

Related Topics