Chapter: 11th English : UNIT 1 : Prose: The Portrait of a Lady

Prose: The Portrait of a Lady

The Portrait of a Lady

Here is a story that brings out the bond between the author and his loving grandmother.

My grandmother,

like everybody’s grandmother, was an old woman. She had been old and wrinkled

for the twenty years that I had known her. People said that she had once been

young and pretty and had even had a husband, but that was hard to believe. My

grandfather’s portrait hung above the mantelpiece in the drawing room. He wore a big turban and loose fitting

clothes. His long, white beard covered the best part of his chest and he looked

at least a hundred years old. He did not look the sort of person who would have

a wife or children. He looked as if he could only have lots and lots of

grandchildren. As for my grandmother being young and pretty, the thought was

almost revolting. She often told us of the games she used to play as a child.

That seemed quite absurd and undignified on her part and we

treated it like the fables of the Prophets she used to tell us.

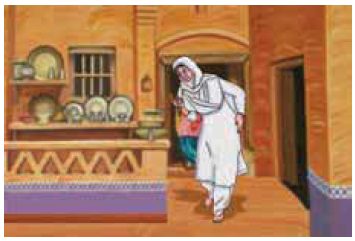

She had always been

short and fat and slightly bent. Her face was a criss-cross of wrinkles running

from everywhere to everywhere. No, we were certain she had always been as we

had known her. Old, so terribly old that she could not have grown older, and

had stayed at the same age for twenty years. She could never have been pretty;

but she was always beautiful. She hobbled about the house in spotless white

with one hand resting on her waist to balance her stoop and the other telling

the beads of her rosary. Her silver locks were scattered untidily over her

pale, puckered face, and her lips constantly moved

in inaudible

My grandmother and

I were good friends. My parents left me with her when they went to live in the

city and we were constantly together. She used to wake me up in the morning and

get me ready for school. She said her morning prayer in a monotonous sing-song while she bathed and dressed me in the hope that I would listen and get to

know it by heart; I listened because I loved her voice but never bothered to

learn it. Then she would fetch my wooden slate which she had already washed and

plastered with yellow chalk, tiny earthen ink-pot and a red pen, tie them all

in a bundle and hand it to me. After a breakfast of a thick, stale chapatti

with a little butter and sugar spread on it, we went to school. She carried

several stale chapattis with her for the village dogs.

My grandmother

always went to school with me because the school was attached to the temple.

The priest taught us the alphabet and the morning prayer. While the children

sat in rows on either side of the verandah singing the alphabet or the prayer

in a chorus, my grandmother sat inside reading the scriptures. When we had both

finished, we would walk back together. This time the village dogs would meet us

at the temple door. They followed us to our home growling and fighting with

each other for the chapatti we threw to them.

When my parents

were comfortably settled in the city, they sent for us. That was a turning-point

in our friendship. Although we shared the same room, my grandmother no longer

came to school with me. I used to go to an English school in a motor bus. There

were no dogs in the streets and she took to feeding sparrows in the courtyard

of our city house.

As the years rolled

by, we saw less of each other. For some time she continued to wake me up and

get me ready for school. When I came back she would ask me what the teacher had

taught me. I would tell her English words and little things of western science

and learning, the law of gravity, Archimedes’ Principle, the world being round

etc. This made her unhappy. She could not help me with my lessons. She did not

believe in the things they taught at the English school and was distressed that

there was no teaching about God and the scriptures. One day, I announced that

we were being given music lessons. She said nothing but her silence meant

disapproval. She rarely talked to me after that.

When I went up to

University, I was given a room of my own. The common link of friendship was snapped. My grandmother accepted her seclusion with resignation. She rarely left

her spinning-wheel to talk to anyone. From sunrise to sunset she sat by her

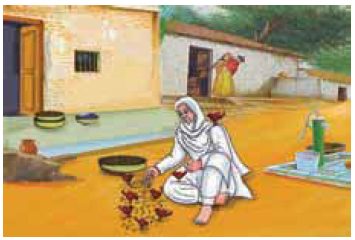

wheel spinning and reciting prayers. Only in the afternoon she relaxed for a

while to feed the sparrows. While she sat in the verandah breaking the bread

into little bits, hundreds of little birds collected round her creating a

veritable bedlam of chirruping. Some

Some even sat on her head. She smiled but never shooed them away. It used to be

the happiest half-hour of the day for her.

When I decided to

go abroad for further studies, I was sure my grandmother would be upset. I

would be away for five years, and at her age one could never tell. But my

grandmother could. She was not even sentimental. She came to leave me at the

railway station but did not talk or show any emotion. Her lips moved in prayer,

her mind was lost in prayer. Her fingers were busy telling the beads of her

rosary. Silently she kissed my forehead, and when I left I cherished the moist

imprint as perhaps the last sign of physical contact between us.

But that was not

so. After five years I came back home and was met by her at the station. She

did not look a day older. She still had no time for words, and while she

clasped me in her arms I could hear her reciting her prayers. Even on the first

day of my arrival, her happiest moments were with her sparrows whom she fed

longer and with frivolous rebukes.

In the evening a

change came over her. She did not pray. She collected the women of the

neighbourhood, got an old drum and started to sing. For several hours she

thumped the sagging skins of the dilapidated

drum and sang of

the home-coming of warriors. We had to persuade her to stop to avoid

overstraining. That was the first time since I had known her that she did not

pray.

The next morning

she was taken ill. It was a mild fever and the doctor told us that it would go.

But my grandmother thought differently. She told us that her end was near. She

said that, since only a few hours before the close of the last chapter of her

life she had omitted to pray, she was not going to waste any more time talking

to us.

We protested. But

she ignored our protests. She lay peacefully in bed praying and telling her

beads. Even before we could suspect, her lips stopped moving and the rosary

fell from her lifeless fingers. A peaceful pallor spread on her face and we knew that she was dead.

We lifted her off

the bed and, as is customary, laid her on the ground and covered her with a red

shroud. After a few hours of mourning we

left her alone to make arrangements for her funeral. In the evening we went to

her room with a crude stretcher to take her to be cremated. The sun was setting

and had lit her room and verandah with a blaze of golden light. We stopped

half-way in the courtyard. All over the verandah and in her room right up to

where she lay dead and stiff wrapped in the red shroud, thousands of sparrows

sat scattered on the floor. There was no chirruping. We felt sorry for the

birds and my mother fetched some bread for them. She broke it into little

crumbs, the way my grandmother used to, and threw it to them. The sparrows took

no notice of the bread. When we carried my grandmother’s corpse off, they flew

away quietly. Next morning the sweeper swept the bread crumbs into the dustbin.

About the Author

Khushwant Singh is an Indian novelist and lawyer. He

studied at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi and King’s college, London. He joined

the Indian Foreign Service in 1947. As a writer, he is best known for his keen

secularism, sarcasm and love for poetry. He served as the editor of several

literary and news magazines as well as two newspapers. Khushwant Singh was awarded

with Padma Bhushan in 1974, Padma Vibhushan by the Government of India and

Sahitya Akademi Fellowship by Sahitya Academy of India. The Mark of Vishnu, A

History of Sikhs, The Train to Pakistan, Success Mantra, We Indians and Death

at my Doorstep are some of his brilliant works.

Related Topics