Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Preoperative Nursing Management

Preoperative Teaching - Preoperative Nursing Interventions

Preoperative Nursing Interventions

PREOPERATIVE TEACHING

Nurses

have long recognized the value of preoperative instruc-tion (Fitzpatrick,

1998). Each patient is taught as an individual, with consideration for any

unique concerns or needs; the pro-gram of instruction should be based on the

individual’s learning needs (Quinn, 1999). Multiple teaching strategies should

be used (eg, verbal, written, return demonstration), depending on the patient’s

needs and abilities. Preoperative teaching is initiated as soon as possible. It

should start in the physician’s office and con-tinue until the patient arrives

in the operating room.

When and What to Teach

Ideally,

instruction is spaced over a period of time to allow the pa-tient to assimilate

information and ask questions as they arise. Frequently, teaching sessions are

combined with various prepara-tion procedures to allow for an easy and timely

flow of informa-tion. The nurse should guide the patient through the experience

and allow ample time for questions. Some patients may feel too many descriptive

details will increase their anxiety level, and the nurse should respect their

wish for less detail.

Teaching

should go beyond descriptions of the procedure and should include explanations

of the sensations the patient will ex-perience. For example, telling the patient

only that preoperative medication will relax him or her before the operation is

not as ef-fective as also noting that the medication may result in light

headedness and drowsiness. Knowing what to expect will help the patient

anticipate these reactions and thus attain a higher degree of relaxation than

might otherwise be expected.

The

ideal timing for preoperative teaching is not on the day of surgery but during

the preadmission visit when diagnostic tests are performed. At this time, the

nurse or resource person answers questions and provides important patient

teaching. During this visit, the patient can meet and ask questions of the

perioperative nurse, view audiovisuals, receive written materials, and be given

the telephone number to call as questions arise closer to the date of surgery.

Most institutions provide written instructions (de-signed to be copied and

given to patients) about many types of surgery (Economou & Economou, 1999).

Deep-Breathing, Coughing, and Incentive Spirometers

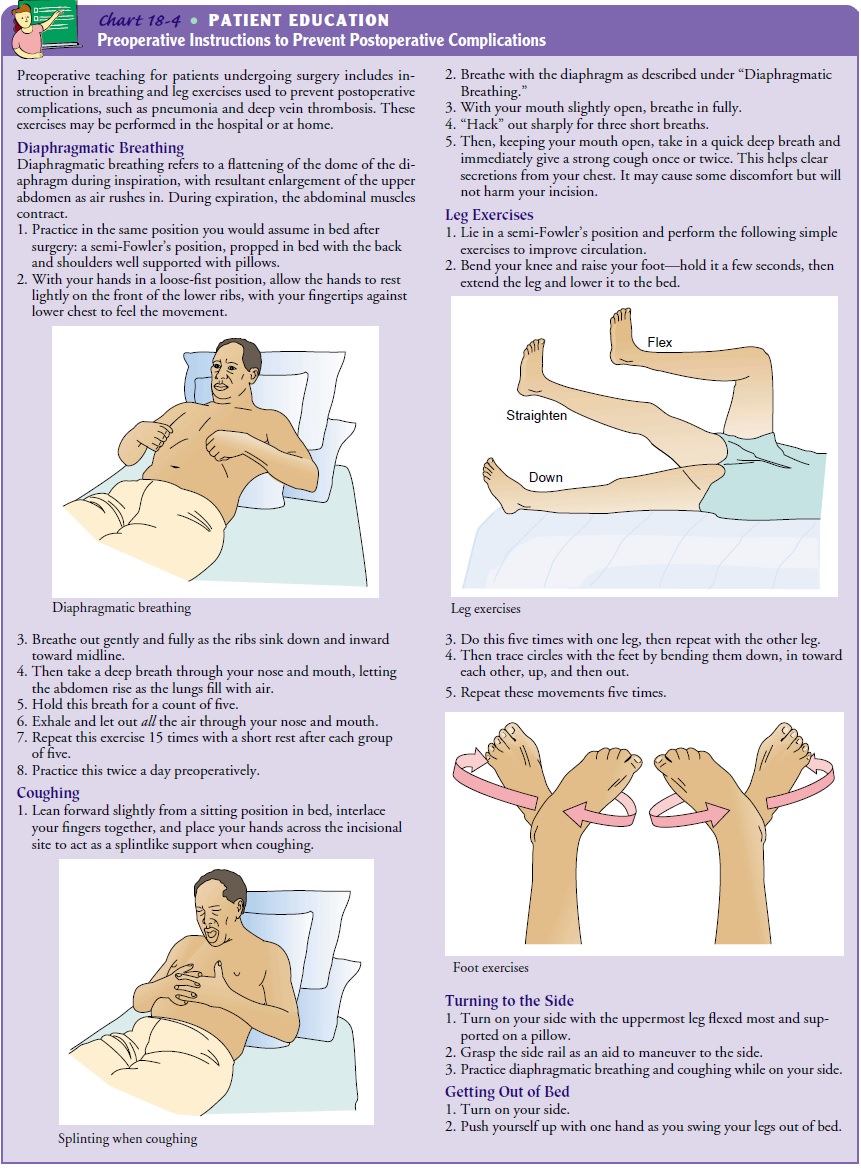

One

goal of preoperative nursing care is to teach the patient how to promote

optimal lung expansion and consequent blood oxy-genation after anesthesia. The

patient assumes a sitting position to enhance lung expansion. The nurse then

demonstrates how to take a deep, slow breath and how to exhale slowly. After

practic-ing deep breathing several times, the patient is instructed to breathe

deeply, exhale through the mouth, take a short breath, and cough from deep in

the lungs (Chart 18-4). The nurse also demonstrates how to use an incentive

spirometer, a device that provides mea-surement and feedback related to

breathing effectiveness. In ad-dition to enhancing respiration, these exercises

may help the patient to relax.

If

there will be a thoracic or abdominal incision, the nurse demonstrates how the

incision line can be splinted to minimize pressure and control pain. The

patient should put the palms of both hands together, interlacing the fingers

snugly. Placing the hands across the incisional site acts as an effective

splint when coughing. Additionally, the patient is informed that medications

are available to relieve pain and should be taken regularly for pain relief so

that effective deep-breathing and coughing exercises can be performed. The goal

in promoting coughing is to mobilize se-cretions so they can be removed. Deep

breathing before cough-ing stimulates the cough reflex. If the patient does not

cough effectively, atelectasis (lung collapse), pneumonia, and other lung

complications may occur.

Mobility and Active Body Movement

The

goals of promoting mobility postoperatively are to improve circulation, prevent

venous stasis, and promote optimal respira-tory function.

The

nurse explains the rationale for frequent position changes after surgery and

then shows the patient how to turn from side to side and how to assume the

lateral position without causing pain or disrupting intravenous lines, drainage

tubes, or other equip-ment. Any special position the individual patient will

need to maintain after surgery (eg, adduction or elevation of an extrem-ity) is

discussed, as is the importance of maintaining as much mo-bility as possible

despite restrictions. Reviewing the process before surgery is helpful because

the patient may be too uncomfortable after surgery to absorb new information.

Exercises of the extremities include extension and flexion of the knee and hip joints (similar to bicycle riding while lying on the side). The foot is rotated as though tracing the largest possible circle with the great toe (see illustrations in Chart 18-4). The elbow and shoulder are also put through range of motion. At first, the patient is assisted and reminded to perform these exercises. Later, the patient is encouraged to do them independently. Mus-cle tone is maintained so that ambulation will be easier.

The

nurse should remember to use proper body mechanics and to instruct the patient

to do the same. Whenever the patient is positioned, his or her body needs to be

properly aligned.

Pain Management

An

assessment should include a determination between acute and chronic pain so

that the patient may differentiate postoperative pain from a chronic condition.

It is at this point that a pain scale should be introduced and its use

explained to the patient.

Postoperatively,

medications are administered to relieve pain and maintain comfort without

increasing the risk for inadequate air exchange. The patient is instructed to

take the medication as fre-quently as prescribed during the initial

postoperative period for pain relief. Anticipated methods of administration of

analgesic agents for inpatients include patient-controlled analgesia (PCA),

epidural ca-theter bolus or infusion, or patient-controlled epidural analgesia

(PCEA). A patient who is expected to go home would receive oral analgesic

agents. These are discussed with the patient before sur-gery, and the patient’s

interest and willingness to use those meth-ods are assessed. The patient is

instructed in use of a pain intensity rating scale to promote effective postoperative

pain management.

Cognitive Coping Strategies

Cognitive

strategies may be useful for relieving tension, over-coming anxiety, decreasing

fear, and achieving relaxation. Exam-ples of such strategies include the

following:

• Imagery—The patient concentrates on a

pleasant experi-ence or restful scene.

• Distraction—The patient thinks of an

enjoyable story or recites a favorite poem or song.

• Optimistic self-recitation—The patient

recites optimistic thoughts (“I know all will go well”).

Instruction for Ambulatory Surgical Patients

Preoperative

education for the same-day or ambulatory surgical patient comprises all the

material presented earlier as well as collaborative planning with the patient

and family for discharge and follow-up home care. The major difference in

outpatient preoperative education is the teaching environment (Quinn, 1999).

Preoperative

teaching content may be presented in a group meeting, on a videotape, during

night classes, at preadmission testing, or by telephone in conjunction with the

preoperative in-terview. In addition to answering questions and describing what

to expect, the nurse tells the patient when and where to report, what to bring

(insurance card, list of medications and allergies), what to leave at home

(jewelry, watch, medications, contact lenses), and what to wear (loose-fitting,

comfortable clothes; flat shoes). The nurse in the surgeon’s office may

initiate teaching be-fore the perioperative telephone contact.

The

last preoperative phone call is designed to remind the pa-tient not to eat or

drink as directed. A fasting period of 8 hours or more is recommended for a

meal that includes fried or fatty foods or meat (Crenshaw, Winslow &

Jacobson, 1999). The anesthesiologist or anesthetist may restrict foods and

fluids for longer periods of time depending on the patient’s fluid status, age,

and pulmonary status and the nature of the surgical procedure.

The purpose of withholding food before surgery is to prevent aspiration. Aspiration occurs when food or fluid is regurgitated from the stomach and enters the pulmonary system. Such inhaled material, which is a foreign substance, is irritating and causes an inflammatory reaction that interferes with adequate air exchange. Aspiration is a serious problem, and mortality is high (60% to 70%). If the patient is assessed as being at high risk for aspiration, the anesthesiologist or anesthetist prescribes more stringent food and fluid restrictions. Fluids may be administered intravenously in some patients to ensure an adequate fluid volume when oral fluids are restricted.

Related Topics