Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : The Endocrine System

Pediatric Tumors : Surgical Pathology Dissection

Pediatric Tumors

General Comments

A number

of tumors are unique to children. These tumors frequently require special

processing to ensure that the diagnosis can be established and appropriate

treatment given. The Children’s On-cology Group (COG) creates, monitors, and

eval-uates therapeutic protocols for pediatric tumors. In the United States,

COG frequently requires that pathologic material be sent to review

patholo-gists to verify the diagnosis and to further classify the tumor.

Additional fresh and frozen tissue is often required for biologic studies,

which are performed at specialized reference laborato-ries. If this tissue is

not collected at the time of surgery, the patient may not be eligible for the

appropriate treatment protocol. Furthermore, as knowledge is accumulated and

protocols change, tissue requirements change. Therefore, patholo-gists who are

processing pediatric tumors need to work closely with their pediatric

oncologists to be aware of the current protocol requirements. Conversely, the

entire specimen cannot be submitted for biologic studies. Sufficient tissue

must be available to establish a histologic diag-nosis. It is vital that the

pathologist be respon-sible for the appropriate triage of this tissue. In many

cases, tissue also needs to be submitted for ancillary diagnostic studies (such

as electron microscopy and cytogenetic analysis). Despite these demands,

pediatric tumors can be pro-cessed easily if a series of steps is routinely

performed at the time of initial processing. Establishing a routine is

particularly important because many biopsies are performed during off-hours.

Overall Guidelines

1. Ensure

that all pediatric tumors are

promptly received in the fresh state. This may entail pro-cessing during

off-hours by on-call personnel.

2. Decide

how much of the specimen is needed for routine histology. This will depend on

the tumor type suspected and the size of the biopsy.

3. Submit

tissue for electron microscopy if appro-priate. It is good practice to put a

small piece of every pediatric tumor in glutaraldehyde. This can then be

embedded, and the decision of whether to section and process can be made at a

later time.

4. Place 1/2 to 1 cc

of minced tumor in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) or equivalent

tissue culture medium and refrig-erate. This material can be submitted for

cyto-genetic analysis, flow cytometry, or mailed to a reference laboratory for

special studies (such as ploidy, gene amplification studies, or fluo-rescence

in situ hybridization).

5. Freeze a

minimum of 1 cc of tumor tissue in liquid nitrogen. This can be submitted to

refer-ence laboratories for protocol studies or held locally in a tumor bank if

available. Normal tissue should also be frozen. If you have lim-ited tissue,

remember that the frozen section control is often inadequate for permanent

his-tology, yet if it is kept frozen it can be used for these studies.

Small Blue Cell Tumors of Childhood

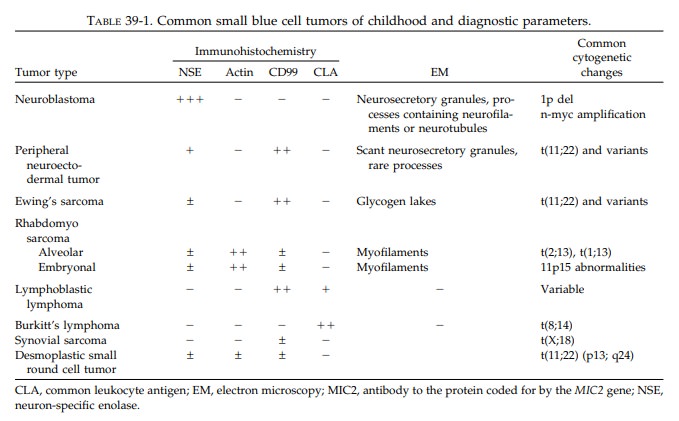

Pediatric

tumors are often embryonal neoplasms showing little or no differentiation by

routinehistology. In particular, at the time of frozen sec-tion, these tumors

appear to be primitive, small, round blue cell tumors. Their diagnosis often

depends on ancillary studies such as immuno-histochemistry, electron

microscopy, and cyto-genetics or molecular genetic analysis. If all pediatric

specimens are processed as delineated in the first section, all necessary

information should be available in a timely fashion. Table 39-1 lists the most

common small blue tumors of child-hood and their pertinent diagnostic features.

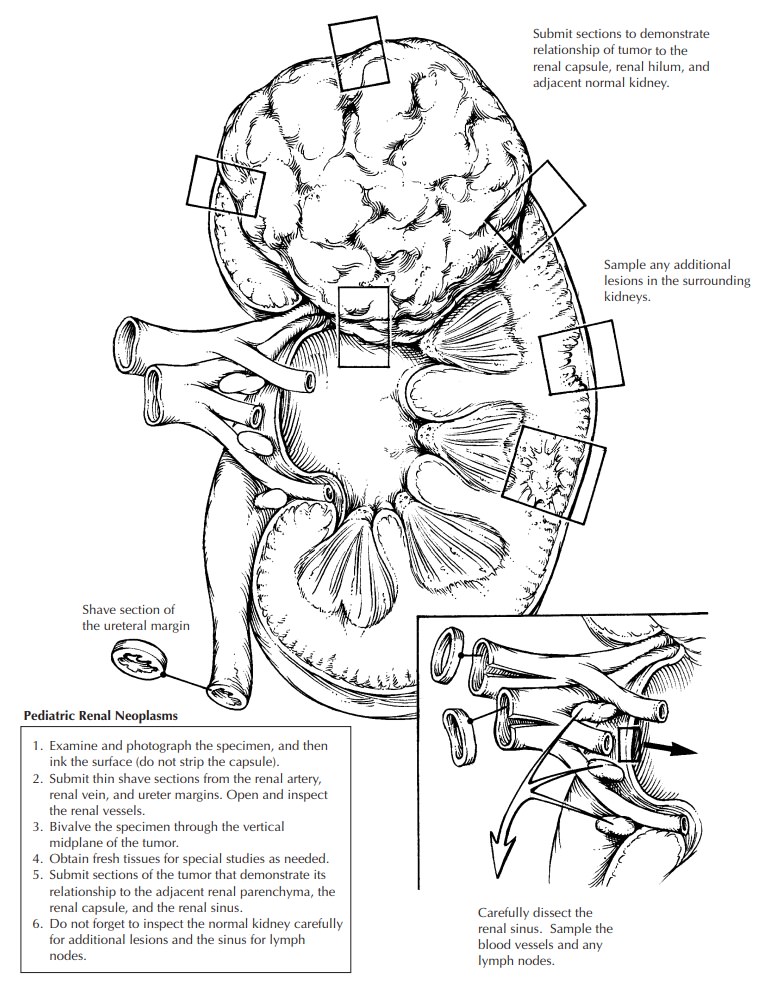

Pediatric Renal Neoplasms

Pediatric

renal tumors are often primarily re-sected and must be carefully processed to

en-sure accurate staging.19Since these tumors are often

bulky and friable and are therefore easily distorted, processing must be

undertaken with care.

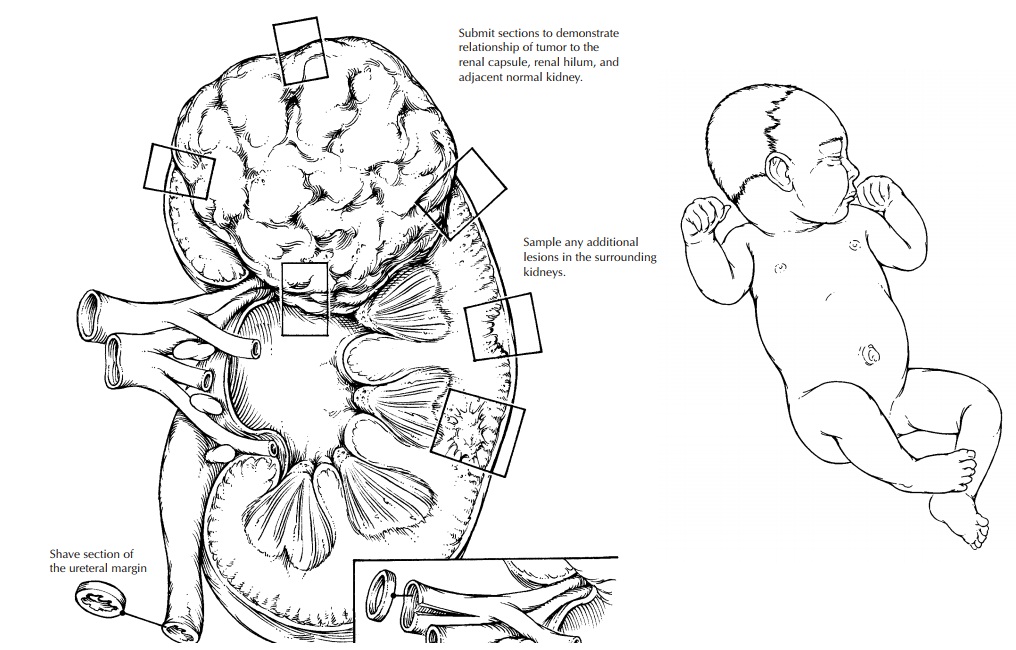

1. Photograph

the nephrectomy specimen before bivalving. Carefully examine the contour of the

kidney and the tumor, and identify poten-tial sites of capsular penetration.

2. Ink the

surface (do not strip the capsule).

3. Submit

shave sections of the vascular and ure-teral margins. The renal vein margin is

particu-larly important.

4. Bivalve

the specimen. The kidney should always be bivalved by the pathologist after steps 1–3 are performed, not by

the surgeon and not in the operating room. Choose your plane of incision

carefully, as the placement of the origi-nal incision determines your ability

to docu-ment the relationship between the tumor and kidney, the tumor and the

renal sinus, etc. The incision should be at or near the vertical mid-plane of

the kidney. This cut should avoid sites of capsular penetration if possible.

5. Obtain

fresh tissues needed for special studies (cytogenetics, frozen, etc.), as

outlined pre-viously. Photograph the bivalved specimen.

6. Make

cuts parallel to the initial bivalving inci-sion at 2- to 3-cm intervals.

Submerge the spec-imen in a large container of formalin. If the formalin can be

refrigerated, color preserva-tion will be enhanced and autolysis slowed.

7. After a

few hours or overnight fixation, the remaining sections may be obtained. Two

slides should be prepared from all tissue blocks to expedite the mailing of

slides to the external review pathologist. The majority of the routine tumor

sections should be taken from the periphery of the lesion, showing the

following:

a. Nature of the tumor–kidney junction.

b. Relationship

of the tumor to the renal capsule, particularly in areas of concern for

capsular penetration.

c. Relationship

of the tumor to the renal sinus.

d. Areas

of the tumor that appear different (e.g., necrosis, hemorrhage). Always

in-dicate the exact site from which each sec-tion is taken. This is most easily

done by taking Polaroid or digital photographs. Drawings are often

insuf-ficient.

8. Carefully

section and inspect the normal kid-ney, particularly adjacent to the tumor. These

areas may show microscopic foci of persis-tent embryonal tissue known as

nephrogenic rests, the potential precursor lesion of nephro-blastomas.

9. Carefully

dissect the hilar and perinephric tissues for lymph nodes. Failure to submit

re-gional lymph nodes may render patients ineli-gible for some low-stage

protocols.

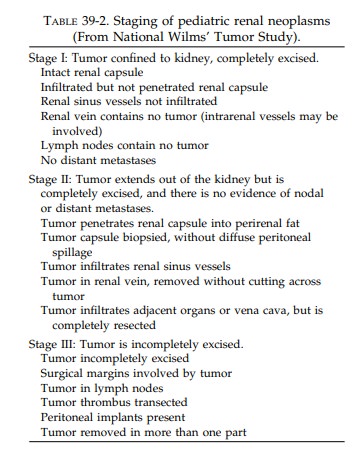

Using the above guidelines for submission of blocks, histologic evaluation should then pro-vide the specific tumor diagnosis as well as the stage. The staging currently used for pediatric tumors is provided in Table 39-2.

The diagnosis of stage II neoplasms depends on the

identifica-tion of either renal capsular penetration or in-vasion of vessels of

the ‘‘renal sinus.’’ The renal sinus is the principal portal of exit for tumor

cells from the kidney and therefore deserves careful study. The renal sinus is

the concave portion of the kidney that contains much of the pelvicalyceal

system and the principal arteries, veins, lymphat-ics, and nerves that pass

through this sinus. It is largely filled with vascularized adipose tissue. The

renal sinus can be recognized histologically by the fact that the renal cortex

lining the sinus lacks a capsule. A thick capsule surrounds the pelvicalyceal

structures and continues to cover the medullary pyramids. The distinction

between stage I and stage II tumors includes either pene-tration of the renal

capsule or infiltration of ves-sels of the sinus. Some stage I tumors can

distort the renal sinus and protrude with a smoothly encapsulated surface

without invading the soft tissue of the renal sinus. Such tumors do not meet

the criteria for upstaging, unless they show renal capsular penetration.

![]()

Important Issues to Address in Your Report on Pediatric Renal Neoplasms

• What

procedure was performed, and what structures/organs are present?

• What

type of neoplasm is present? The most common diagnoses in children are Wilms

tumor, clear cell sarcoma of kidney, rhabdoid tumor, congenital mesoblastic

nephroma, and renal cell carcinoma. If Wilms tumor, state whether the histology

is favorable or unfavor-able. Unfavorable histology is based on the pres-ence of

cells with nuclei four times the size of surrounding blastemal cells and the

presence of aberrant, multipolar mitotic figures. If unfa-vorable histology

(also called anaplasia) is pres-ent,

comment on its extent (focal or diffuse).

• What is

the size of the tumor (weight and greatest dimension)?

• Are any

margins involved?

• Is the

renal vein involved by tumor?

• Is renal

capsular penetration present?

• Is renal

sinus invasion present?

• Has the

tumor metastasized to regional lymph nodes? Record the number of metastases and

the total number of lymph nodes examined.

Related Topics