Rural Life and Society | Chapter 3 | History | 8th Social Science - Peasants Revolts | 8th Social Science : History : Chapter 3 : Rural Life and Society

Chapter: 8th Social Science : History : Chapter 3 : Rural Life and Society

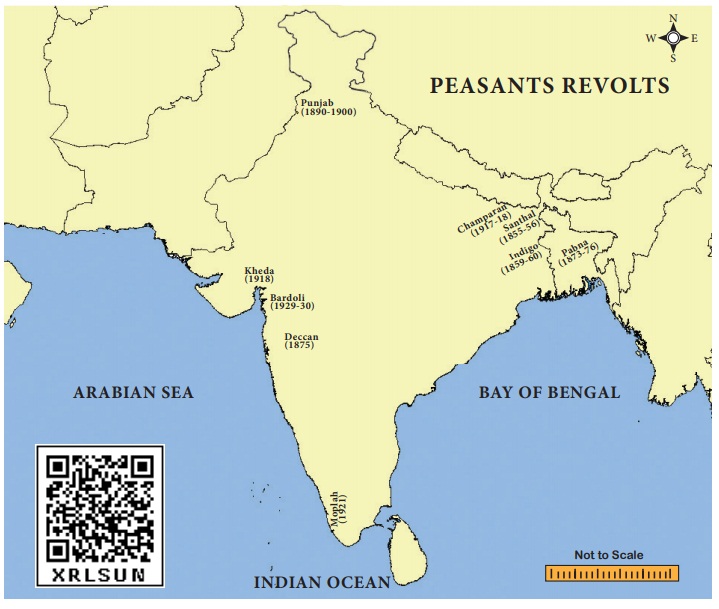

Peasants Revolts

Peasants

Revolts

The

British rule in India brought about many changes in the agrarian system in the

country. The old agrarian system collapsed and under the new system, the

ownership of land was conferred on the Zamindars. They tried to extract as much

as they could from the cultivators of land. The life of the peasants was

extremely miserable. The various peasant movements and uprisings during the

19th and 20th centuries were in the nature of a protest against of the existing

conditions under which their exploitation knew no limits.

The Santhal Rebellion

(1855-56)

The

first revolt which can be regarded as peasants’ revolt was the Santhal

Rebellion in 1855-56. The land near the hills of Rajmahal in Bihar was

cultivated by the Santhals. The landlords and money-lenders from the cities

took advantage of their ignorance and began grabbing their lands. This created

bitter resentment among them leading to their armed uprising in 1855.

Consequently, under the belief of a divine order, around 10,000 Santals

gathered under two Santhal brothers, Siddhu and Kanhu, to free their country of

the foreign oppressors and set up a government of their own. The rebellion

assumed a formidable shape within a month. The houses of the European planters,

British officers, railway engineers, zamindars and money-lenders were attacked.

The rebellion continued till February 1856, when the rebel leaders were

captured and the movement was put down with a heavy hand. The government

declared the Parganas inhabited by them as Santhal Parganas so that their lands

and identity could be safeguarded from external encroachments.

Indigo Revolt

(1859-60)

The

Bengal indigo cultivators strike was the most militant and widespread peasant

uprisings. The European indigo planters compelled the tenant farmers to grow

indigo at terms highly disadvantageous to the farmers. The tenant farmer was

forced to sell it cheap to the planter and accepted advances from the planter

that benefitted the latter. There were also cases of kidnapping, looting,

flogging and burning. Led by Digambar Biswas and Bishnu Charan Biswas, the

ryots of Nadia district gave up indigo cultivation in September 1859. Factories

were burnt down and the revolt spread. To take control of the situation, the

Government set up an indigo commission in 1860 whose recommendations formed

part of the Act VI of 1862. The indigo planters of Bengal, however, moved on to

settle in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. The newspaper, Hindu Patriot brought to

light the misery of the cultivators several times. Dinabandhu Mitra wrote a

drama, Nil-Darpan, in Bengali with a view to draw the attention of the people

and the government towards the misery of the indigo-cultivators.

Pabna Revolt (1873-76)

Pabna

Peasant Uprising was a resistance movement by the peasants against the

oppression of the Zamindars. It originated in the Yusufshahi pargana of Pabna

in Bengal. It was led by Keshab Chandra Roy. The zamindars routinely collected

money from the peasants by the illegal means of forced levy, abwabs, enhanced

rent and so on. Peasants were often evicted from land on the pretext of

non-payment of rent.

Large

crowds of peasants gathered and marched through villages frightening the

zamindars and appealing to other peasants to join with them. Funds were raised

from the ryots to meet the costs. The struggle gradually spread throughout

Pabna and then to the other districts of East Bengal. Everywhere agrarian

leagues were organized. The main form of struggle was that of legal resistance.

There was very little violence. It occurred only when the zamindars tried to

compel the riots to submit to their terms by force. There were only a few cases

of looting of the houses of the zamindars. A few attacks on police stations

took place and the peasants also resisted attempts to execute court decrees.

Hardly zamindars or zamindar’s agent were killed or seriously injured. In the

course of the movement, the riots developed a strong awareness of the law and

their legal rights and the ability to combine and form associations for

peaceful agitation.

Deccan Riots (1875)

In

1875, the peasants revolted in the district of Poona, that event has been

called the ‘Deccan Riots’. The peasants revolted primarily against the

oppression of local moneylenders who were grabbing their lands systematically.

The uprising started from a village in Poona district when the village people

forced out a local moneylender from the village and captured his property.

Gradually, the uprising spread over 33 villages and the peasants looted the

property of Marwari Sahukars. The uprising turned into violent when the

Sahukars took help of the police. It was suppressed only when the army was

called to control it. However, it resulted in passing of the Deccan

Agriculturists Relief Act’ which removed some of the most serious grievances of

the peasants.

Punjab Peasant

Movement (1890-1900)

The

peasants of the Punjab agitated to prevent the rapid alienation of their lands

to the urban moneylenders for failure to pay debts. The British India did not

want any revolt in that province which provided a large number of soldiers to

the British army in India. In order to protect the peasants of the Punjab, the

Punjab Land Alienation Act was passed in 1900 “as an experimental measure” to

be extended to the rest of India if it worked successfully in the Punjab. The

Act divided the population of the Punjab into three categories viz., the

agricultural classes, the statutory agriculturist class and the rest of the

population including the moneylenders. Restrictions were imposed on the sale and

mortgage of the land from the first category to the other two categories.

Champaran Satyagraha

(1917-18)

The

European planters of Champaran in Bihar resorted to illegal and inhuman methods

of indigo cultivation at a cost which was wholly unjust. Under the Tinkathia

system in Champaran, the peasants were bound by law to grow indigo on 3/20 part

of their land and send the same to the British planters at prices fixed by

them. They were liable to unlawful extortion and oppression by the planters.

Mahatma Gandhi took up their cause. The Government appointed an enquiry

commission of which Mahatma Gandhi was a member. The grievances of the peasants

were enquired and ultimately the Champaran Agrarian Act was passed in May 1918.

Kheda (Kaira)

Satyagraha (1918)

In the Kheda District of Gujarat,

due to constant famines, agriculture failed in 1918, but the officers insisted

on collection of full land revenue. The local peasants, therefore, started a

‘no-tax’ movement in Kheda district in 1918. Gandhi accepted the leadership of

this movement.

Gandhiji organised the peasants to

offer Satyagraha and opposed official insistence on full collection of

oppressive land revenue despite the conditions of famine. He inspired the

peasants to be fearless and face all consequences. The response to his call was

unprecedented and the government had to bow to a settlement with the peasants.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel emerged as an important leader of the Indian freedom

struggle during this period.

Moplah Rebellion (1921)

The Muslim Moplah (or Moplah)

peasants of Malabar (Kerala) was suppressed and exploited by the Hindu

zamindars (Jenmis) and British government. This was the main cause of this

revolt.

The

Moplah peasants got momentum from the Malabar District Conference, held in

April 1920. This conference supported the tenants’ cause, and demanded

legislations for regulating landlord-tenant relations. In August 1921, the

Moplah tenants rebelled against the oppressive zamindars. In the initial phase

of the rebellion, the Moplah peasants attacked the police stations, public

offices, communications and houses of oppressive landlords and moneylenders. By

December 1921, the government ruthlessly suppressed the Moplah rebellion.

According to an official estimate, as a result of government intervention, 2337

Moplah rebels were killed, 1650 wounded and more than 45,000 captured as

prisoners.

Bardoli

Satyagraha (1929-30)

In 1928, the peasants of Bardoli

(Gujarat) started their agitation under the leadership of Sardar Vallabhbhai

Patel, in protest against the government’s proposal to increase land revenue by

30 percent. The peasants refused to pay tax at the enhanced rate and started

no-tax campaign from 12 February 1928. Many women also participated in this

campaign.

In

1930, the peasants of Bardoli rose to a man, refused to pay taxes, faced the

auction sales and the eventual loss of almost all of their lands but refused to

submit to the Government.

However,

all their lands were returned to them when the Congress came to power in 1937.

Related Topics